|

145-day protest in Chillicothe In Motion Magazine: What were some of the early campaigns of the MRCC? Rhonda Perry: The MRCC was founded in 1985, and one of the first major campaigns after the founding of the organization, was a 145-day protest action at the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) office in Chillicothe, Missouri. That action had two major purposes. One, an immediate purpose, to get rid of the county supervisor there who was foreclosing on farmers left and right against the law. He was later deemed an abusive county supervisor and eventually had to take some how-to-get-along classes and got transferred to some place else. The other major purpose of the 145-day action was to put a significant amount of pressure on policy makers to pass the 1987 Credit Act, which did eventually get passed. This particular action was actually an occupation of the USDA for literally 145 days. That meant there was a building that was set up in the parking lot at the USDA office. Anyone who went in or out had to pass all these farmers who had taken over the parking lot of the USDA building. There was a Quonset hut set up and there were farmers who manned the phones in there, 24 hours a day. They had what they called the "Monday Night Meetings". You'd call your house, or call to my parents' house, "What's going on?" "Well, Dad and Mike are at the Monday night meeting." It became a common-place gathering for farmers to talk about what was going on -- what was happening to them, what was going on with their loans -- and to get engaged with what was going on in other parts of the country around issues of credit and also civil liberties. But they didn't just occupy this space for 145 days and make demands; they engaged their allies. The Jewish Community Relations Bureau became a part. They came down and took a tour of farms to get an understanding about what farmers were dealing with. And that subsequently turned into a farmer project for the Jewish Community Relations Bureau in which they did a tremendous amount of work on farm issues around what the farmers were saying they most needed. They also brought in the civil rights community as they had in the early days, and the labor community as well. Nearly every action that was going on at that USDA office and at others, involved the Food and Commercial Workers, the UAW, the Civil Rights Movement, the Jewish Community Relations Bureau. In Chillicothe, this was an incredible experience because people like my parents they didn't know any Jewish people. They had never met any Jewish people. It was an awareness building about who the enemy was and who the enemy really was not. It was a life changing experience for a lot of people. Jesse Jackson came in. They also had 15,000 people in Chillicothe when they had John Mellencamp who came in to stand up for farmers in that USDA parking lot, right on Main Street at Chillicothe. It was quite an array of tactics that were used during that 145 days. And it was based on passing this policy prescription to relieve the immediate crisis around the country, as well as also to meet the immediate needs of farmers there by getting rid of this supervisor. Immediate tactics: Consistent strategies It was during that same period of time that Farm Aid first came into existence, in 1985. This action, then, started in 1986 and there was a grant from Farm Aid to do an emergency food distribution there. Hundreds of farmers were standing in line to get food in Chillicothe. They couldn't afford to buy food. Also, we did these distributions in several other small towns around the area. Then, the women, who were basically running the show, said, "Look, we need to set up a program. We can't just do this one-time with this grant. We've got to set up some kind of food program." Out of that came the only statewide rural emergency food program, which we started at that point in 1986. It ran until 1992 when we turned it into the Food Cooperative Program. We stopped doing it as an emergency food program and turned it into a cooperative effort among all of our chapters. Those beginning campaigns in some ways look really different. We might not do a 145-day protest today. But the organizing strategies look very much the same as they always have. Those strategies include, getting the policies you need trying to provide immediate resources for people, activities and strategies like direct action, credit counseling, emergency food -- organizing strategies that involve bringing people together who otherwise would never have come together. Breaking down those barriers that tend to keep people apart. We have maintained those strategies. The issues have changed somewhat but the strategies have been the same and the goals have been the same throughout the history. This has really proven to work well for our organization. In the beginning, it was credit. Our immediate issue was credit and stopping foreclosures. The policy piece was passing the 1987 Credit Act, which did happen. This immediately stopped hundreds of thousands of foreclosures. The government was foreclosing on farmers and getting less money than they would have gotten if they had worked out a buyout arrangement with the farmers. The taxpayers were taking it, the farmers were taking it, the rural communities were taking it; and nobody was benefiting from this system. The 1987 Credit Act said that the government should keep the farmer on the land if that is the least-cost option to taxpayers. That's kind of like a big "duh", common sense. Who would think it would take legislation in order to make that happen? But it did, and the '87 Credit Act was implemented and thousands of farmers were able to restructure their debt under the 1987 Credit Act, as the least-cost option for the government and taxpayers.

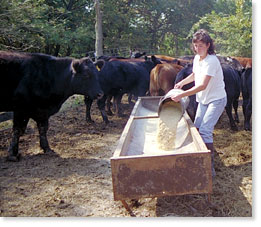

It was at that point that a lot of organizations which had been in place early on during the fights of the '80s, they made choices. They were either going to continue to do the service pieces and policy pieces, but not necessarily build a membership organization; or they would decide, like we did, that our major purpose was to build a membership organization. A tremendous number of the organizations who did other things, who had other strategies, like becoming more think-tankish or who continued to work solely in the credit arena, most of those organizations aren't here any more. The organizations that are still around, really, were the ones who built a membership base. Because we had a strategy of building a membership organization, instead of becoming some other kind of entity to address farm issues, that led to our longevity and our ability to then take on the other pertinent issues that were going to come up over the next twenty years. Now, we are at twenty years later, and you can clearly see changes in the issues. We have gone from credit to factory farms to corporate concentration to turning what was an emergency food program into a food cooperative program. But I think the strategies are very much the same as they were. We have five general programs that we run: the Food Cooperative Program; Patchwork Family Farms; the Factory Farm Organizing Project; the Farm and Food Policy Project; the statewide Local Food Initiative. Right now, we have our food program, which is now a cooperative program. We have eleven chapters of food co-ops around the state. They purchase an incredible amount of food. It works by chapter leaders and chapter members putting in their time and resources and opinions into how to make the program run. They distribute, every month, thousands of pounds of food to people who otherwise would not have access to quality food in their rural community -- which seems totally crazy. Another on-the-ground program that is meeting an immediate need is Patchwork Family Farms, which is keeping hog farmers in business who are able to raise hogs sustainably without continuously feeding anti-biotics, without growth hormones, providing access to fresh air and sunshine; enabling those farmers to earn a fair price. That program has proven even to be more important than we had expected when we set it up with the continued corporate concentration of the hog industry. Literally 75% of Missouri's hog farmers have gone out of business in the last decade. Two other programs that we've had quite a long time are our Factory Farm Organizing Project and our Farm and Food Policy Project. And fifth, we've now added an additional statewide Local Food Initiative that we are working on jointly with the University of Missouri. You can see from just the existence of our current programs that we've still got the programs that are on the ground, meeting the immediate needs of farmers and rural people, and we have the policy programs. But, obviously, those aren't totally separated programs. We try, for example, to engage people who are members of our food co-op and members of Patchwork Family Farms into the policy debate and the policy arena. And, vice versa, we try to always have the folks who get involved with us for the policy, get an understanding about what is going on with our food co-op and Patchwork and why those play an integral role in what we want to do. Patchwork Family Farms: A sustainable alternative In Motion Magazine: You said that Patchwork has become more important than you originally thought it would. Do you see any connection between the attempt to pursue sustainable production and people participating more in the way they are running their lives? Rhonda Perry: I think two things have made it important. One has been the incredible volatility of the hog market, especially since 1998. In the '90s alone, when we lost 75% of our state's hog farmers, none of our Patchwork farmers were lost in that 75%. This is a testament in and of itself. The other thing that makes it important is producers are looking for alternative ways to raise hogs that will allow them to do things like Patchwork Family Farms and take more control over the production of their animal and the marketing to the consumers. Missouri has been very, very far behind in sustainable livestock production, as a state. We haven't had funds. We haven't had the research. We haven't had the opportunities that other states, who have made much of more a commitment, like Minnesota, have had. In 2003, Patchwork Family Farms took ten of our producers up to Minnesota and we saw state-supported sustainable hog production models, which was just unbelievable. It was a great experience and from that came some of our producers who are now trying alternative methods. And this is an interesting thing about how our programs relate. As part of our Farm and Food Policy Project, we engaged a tremendous number of people in a fight to save our sustainable ag (agriculture) program in the Department of Ag in the state, which they were cutting. We forced them, just by sheer numbers of people demanding to keep the program, to continue to provide small grants for sustainable demonstration grants. They hadn't typically done a lot of livestock, yet two of our Patchwork producers got grants this year to do two very different sustainable hog-raising demonstration projects that can now be shared with not only other Patchwork producers but other livestock farmers around the state. I think we are moving in a direction in which the value of organizations like ours to make a difference in, specifically, sustainable livestock is pretty incredible. That's how it was in the other states that we went to visit. It wasn't the state that said, "Oh, we need to have sustainable livestock". It was organizations like ours, like Land Stewardship Project in Minnesota, that organized the demand for it, and the state ultimately did do those things. I think, in the case of Patchwork, we have been an important piece of the landscape in Missouri, and somewhat nationally, for eight to ten years now. I don't want to overstate the importance of it, but I think in a state like Missouri it has been invaluable. In Motion Magazine: And it also specifically helps the farmers involved live? Rhonda Perry: Absolutely. We pay 15% above market price, or 43 cents a pound, which is generally assumed to be cost of production. At the least, the hogs that they sell through Patchwork they are going to get a fair price for. We can't buy every hog from every producer. Someday we want to be able to buy every hog from every producer. And certainly we can't control the market place, although we are trying to control the damage that can be done through our Farm and Food Policy Project. But Patchwork clearly has helped them stay on their land. You will hear nearly every producer say, "I probably wouldn't be raising hogs if it weren't for Patchwork Family Farms." And, now they are not only raising hogs, but they are looking at sustainable alternatives that they think can cut their costs and add to their sustainability. It has created a sense of instead of "Oh, it's just a matter of time before I'll be going out of business," which is what the majority of hog farmers had thought, to now we have more farmers who are thinking ahead about how they can use this operation as part of an integrated diversified operation and make it more sustainable for the future. They are planning on staying in business and that alone is a big deal. In Motion Magazine: How many people are in the Food Cooperative Program? Rhonda Perry: 2,300 participant families, in the course of a year. Obviously, the co-op is primarily low-income, but we don't have standards. You don't have to come in and prove that you are destitute or that you are eligible for federal food stamps. You just have to know that this is a good deal and you want access to the program and you obviously need it. People don't typically go around standing in line and contributing their volunteer hours, hundred of volunteer hours are contributed to the program, unless it is a viable program for you that you need. Of the 2,300 families who participate each year in the program, I think something like 85% of them said in our last survey that this program was crucial to meeting their food needs. Of course, we also found that 70% of the folks in the Food Co-op, in one survey, made less than $13,499 a year. Clearly, they had little or no access to quality food. And this seems absolutely nuts; that you can live here in the middle of the heartland, in rural communities that were historically the centers for agricultural production, and you've got all of these people who do not have access to quality food and cannot afford quality food. The goal of this program is two-fold, once again. It is to meet the immediate needs that people have for high quality food coming to their area. And it's also to engage the people that participate in the co-op in issues that they think are affecting their community. The co-op members have played a major role in a number of issues over the last three years, specifically: healthcare, Medicaid, and food stamps. Food stamps, healthcare, Medicaid In Missouri, we have played a big role in the rural communities in engaging our members in knowing what the rules were on food stamps and engaging in food stamps. We went from being one of the lowest states in eligible people who participate in the food stamp program to becoming number two in people who are eligible participating in the program. We did an incredible amount of work on that. Our chapters took it on as an issue to make sure that their people had an understanding that they could access food stamps and how to do so. On the issues of healthcare, they have worked a lot on single-payer healthcare, back when that was a viable option in our state. Now, it has been a fight to save the healthcare that we have through the state by fighting to save Medicare and Medicaid in the state. That has been a major fight for two years. They also did an incredible amount of work around getting rid of the state sales tax on food. These chapters don't just do emergency food distributions. They are pooling their money, their time, their resources, and their organizing skills, much of which they learned through the chapters themselves. And these are typically people who would not otherwise be participating in the democratic process. They become members. Join the chapter that they work on. Sign the petitions. Go to the state capital. Testify at events. For the first time in their lives, they are participating in a process that can ultimately help them survive. That is empowering and it is very much unique in rural Missouri. This year, as part of our Local Food Initiative, we made an attempt to integrate local food into the co-op. We purchased nearly all of our produce from June until August from local farmers, which amounts to a decent amount of money. Just under $20,000 worth of money was put into farmers' pockets and that provided quality produce, raised in Missouri, to our co-op chapters. I think we have a good chance to use our Local Food Initiative to provide local food and to be able then to talk about local food within our co-op. Factory Farm Organizing Project Another of our programs is our Factory Farm Organizing Project, which has been an ongoing project since 1995. We organized around factory farm issues starting 1989 when the first factory farm came to Missouri. We were way far ahead of our time, because at that point there were no factory farms anywhere except North Carolina. Nobody knew what they were, what the devastation was going to be. Farmers thought they could sell them their genetic seed stock. They thought they could use the processing plant. There was an incredible division, at that point in time. Now, anybody in Missouri who hears the words "factory farm" automatically thinks, "That is a real bad thing." But back then people didn't think that. It was a different environment and we had to work for the last ten years to create the basis for which people now have an understanding of what factory farms do economically and environmentally to family farmers, rural communities, to workers. That has been a very long process, but we have had some significant victories along the way. One was the legislation we got passed in 1996, which provided unheard of safeguards. I don't think any other state in the country had these safeguards in place. And most still don't. They included public notification; set-backs from CAFOs (Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations / factory farms); an indemnity fund or a bonding for if they went out of business and left a mess. Missouri was one of the first states in which an individual permitting system was put in place. We got that in the early nineties from sheer power in organizing. Again, the strategies and tactics have been very much the same. We wanted this policy prescription but we knew we weren't going to get it unless we built the power in a way that included helping people on the ground. Literally trying to fight and stop factory farms before they could get up, but also doing direct actions. Taking on the corporations themselves right at their own corporate gates. Campaign for Family Farms and the EnvironmentIn 1995, with the help of other organization from the Midwest, we helped form a massive campaign called the Campaign for Family Farms and the Environment (CFFE) whose goals were to challenge the corporate takeover of the hog industry and to use all kind of tactics from direct actions to policy initiatives to stop the factory farm system from becoming the dominant model of livestock production. (Current members of the CFFE include the Missouri Rural Crisis Center, Minnesota’s Land Stewardship Project, Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement, Citizens Action Coalition of Indiana, and Illinois Stewardship Alliance.) The Premium Standard Farms Model We kicked that off on April 1, 1995 with a huge action right across the road from Premium Standard Farms, at that point the largest hog producer in the world. It was in three counties in north Missouri. Right across the road we had Willie Nelson and a rally with 3,500 people at the intersection of two gravel roads, in truly the middle of nowhere. It has been a long, long journey down the factory farm road from when nobody was challenging factory farms to now, when a number of states all around the country have been challenging the factory farm system of livestock production. You know, there's been a lot of bad things that have happened in factory farms, the loss of family farm producers, but their model, their goal, in 1990, was Premium Standard Farms was going to be the flagship of the industry. It was a completely new model of corporate livestock production. The poultry industry had already gone corporatized. They had done that by contracting with farmers to raise poultry; that is a real, real bad model. But this new model was going to take the industry much faster. Premium Standard Farms was the model. Everyone was looking to it. Tyson was looking at it. They were not contracting out with farmers. The corporation in this case owned the land, owned the hogs, paid people to work in their factory farm plants. They owned the processing. It was owned from the genetics to the bacon. There was no participation from the outside. The company was in total control. In part because of our exposure, our complete exploitation of this company's record and how horrible they were, and the publicity that we got around that, ultimately that company went bankrupt and was bought out by Continental Grain. The industry could not continue down the road of being completely vertically integrated. Now, they do a lot of contracting out. It slowed down the way the industry was going to vertically integrate itself. There are a lot of bad things that we can look at that factory farms have done to states like Missouri. The economics of them don't work. The environment doesn't work with them. We significantly halted that method of taking over the hog industry so that it had to be done in a slow enough way that organizations and communities all over the country have been able to challenge them, and in many cases stop them from coming in. The Farm and Food Policy Project is our work in the state, but mostly nationally and internationally, on issues around farm, food, and trade policy. That's pretty broad so it ends up covering a lot of issues from the CAFTA (Central American Free Trade Agreement) fight, to GMOs (genetically modified organisms), to international supply management agreements. It's been an incredible program for us because we have been able to engage members of our Food Co-op Program, Patchwork Family Farms, and our Factory Farm Organizing Project into the larger debates around farm and food policy at the national and international levels. I think it is safe to say that we, as an organization, have been able to play a leadership role in a number of national and international organizational coalitions and provide a farmer voice for those coalitions, including: the National Family Farm Coalition, the Community Food Security Coalition, Via Campesina, the international organization that we work with most, and the Rural Coalition. I think that we have done a decent job at ensuring farmer voices are heard throughout the national and international organizations that we are a part of. One of the major issues that we are working on is the next Farm Bill. Our goal again is to make sure that farmers are at that table. We are putting on that table our policy prescriptions. One of those is the Food From Family Farms Act, which is an act that would: generate fair prices for farmers and fair prices for consumers; attempt to stop corporate consolidation in agriculture; and ensure a degree of food security through farmer-owned grain reserves and supply management programs. Our newest program, our statewide Local Food Initiative, is a joint project with the University of Missouri. I would say with just the fact that we are doing a joint project with the University of Missouri we should declare victory. Historically this land-grant university, the University of Missouri, has played a particularly bad role, using taxpayer dollars to subsidize studies, which "lo and behold" showed that factory farms were going to be the most incredible model for the state. They have played a very bad role for family farmers and rural communities. But there are some great people at the university that we are working with on this project, mostly from the Rural Sociology Department. We are excited about our Local Food Initiative and increasing the understanding of local food and demonstrating the economic and environmental viability of local food, particularly in Missouri. We are working in three geographical areas: mid-Missouri, Kansas City, and St. Louis. Being able to use that program, for example, to increase the purchases of local food for our food cooperative and increase the understanding of our cooperative members about it, shows how we are able as an organization to use successes and victories and work in one of our projects to meet the immediate needs of our members in other projects. By having a Local Food Initiative and being able to seek out and access local food and then literally put that food into the mouths of people who would probably never have access in their little rural community to locally-raised food, I think is a big success. Those are the basic five program areas and, again, I think you can see the strategies of meeting immediate needs, doing the on-the-ground organizing, and ultimately working on policy prescriptions for more long-term change that we think we need to benefit not only the members of our organization but farmers and rural people all across the country. The MRCC and the U.S. Supreme Court In Motion Magazine: How did you end up sitting in the Supreme Court? Rhonda Perry: As part of our Factory Farm Organizing Project. It was pretty interesting because as we were going to our state capital to demand the policies to protect rural communities and family farmers from this environmentally devastating and economically devastating system of factory farm livestock production, every time we were at the state capitol or at the county commission meetings, who was on the other side testifying -- wrong, demanding -- that we had to have factory farms in the state? It was, "The only thing that was going to save us." It was the Missouri Pork Producers Association, and the National Pork Producers Council at the national level. Everywhere we went, that's who was standing there saying, "We represent the hog farmers of the state," and "We represent America's hog farmers," and "We have got to have this system of livestock production." We knew we had to directly take on the Missouri Pork Producers, the National Pork Producers Council. And, as the Campaign for Family Farms and the Environment, the coalition that was built regionally in the Midwest to challenge these factory farms, we were challenging them. We were there every step of the way. At some point, though, they got a little testy with us and they hired a high-powered spy firm called Mongoven, Biscoe & Duchin, / (See: Hugh Espy, "Summary of AMS Audit of NPPC)", In Motion Magazine, April 12, 1999) to literally spy on five organizations, including the Missouri Rural Crisis Center, the Land Stewardship Project, and Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement. These were organizations that were part of the Campaign for Family Farms and the Environment and they were investigated by this spy firm to determine how they could get rid of us as an adversary. What's more, they used check-off dollars to hire that spy firm to spy on us. It was great because we got the spy report and one of the things it said about the Missouri Rural Crisis Center was "you can never work with this organization because they are too in touch with their members." The National Pork Producers Council and the pork check-off It was a prime example of the arrogance on the part of this commodity organization. And there are organizations like this for every commodity we sell: soybeans, corn, hogs, cattle. But in this case, because we were challenging the corporatization of the hog industry, we clearly were really pissing off the organization that had always been able to say they represented the hog farmers of the country. What is interesting about this is the only way they have been able to say they represent the hog farmers of this country is because they get our money, whether we like it or not, by way of a check-off which we have to pay. Forty cents for every hundred dollars you sell goes to the National Pork Board. Historically, the National Pork Producers Council was the recipient of that money which they were then spending to use against us. They were so out of touch with the hog farmers of this country that here we had hog farmers in Missouri, Minnesota, Iowa, who were the ones who were challenging these factory farms, challenging this organization who was getting their money. The NPPC had no clue. The executive director, the CEO, of the National Pork Producers Council at one point declared war on the Missouri Rural Crisis Center and the Campaign for Family Farms, which were their own members, which were hog producers. The National Factory Farms Council So, after they had spent the check-off dollars to hire the spy firm for us, we took them on directly. We went right to their doorstep, again with hundreds of farmers and Willie Nelson. We renamed them the National Factory Farms Council by hammering a huge sign into their front yard (which spelled this out). I don't think they ever really got over that. They just fit right into that description of themselves. Ultimately, what transpired was our members, and members from the other organizations in the Campaign for Family Farms said, "We've got to take their money away. That's our money and we've got to take it away." We started a campaign to take on the pork check-off because what we saw was it was very hard for us to get to either the corporations that we wanted to take on, or the policy makers that we needed to take on, when we had this entity standing in the way saying that they were us. And they had our money to do it. It was an ambitious strategy to take away their money. By law we had to gather 15% of the signatures of all the hog farmers in the country to petition the USDA to hold a vote. We did that. We needed 15,000 hog farmers to get the signatures. We turned in over 19,000 signatures. USDA did ultimately hold a vote. Secretary Glickman held a vote in 2000. We had to beat up the USDA to get them to announce the vote so we suspected that we had won, and we had. Secretary Glickman announced the vote in January of 2001. Secretary Glickman announced that the hog farmers had won the vote to get rid of the check-off and he started the proceedings to end the check-off. Secretary Veneman and the lawsuit However, Secretary Veneman (President G. W. Bush's first secretary of agriculture) came in before that process was complete and cut a deal with the National Pork Producers Council that did not include ending the check-off. Basically, sending a message to farmers that she didn't give a damn what producers had to say about the check-off. She was keeping it in place. We, then, filed a lawsuit attempting to force her to end the check-off based on the producer vote. Before that case was ruled on, though, there was a case from the Supreme Court declaring the mushroom check-off unconstitutional. We added to our case a First Amendment claim on the check-off claiming that it was a violation of our First Amendment rights to be forced to pay into a program that espoused a message to which we did not agree. We were saying, "They are using our money to put out a message that says 'Buy pork,' not 'Buy pork from family farmers', 'Buy pork' ". And that means buying factory farm pork is just as good as buying from family farmers, which we don't agree with. They used our money to do research to demonstrate numerous things. How do you take the odor out of confinement operations? How do you get rid of factory farm odor? Those were our check-off dollars, six million a year, which they spent on research on how to take the odor out of factory farm pig manure. They did research on how to convince the public that antibiotics in livestock are good for consumers, instead of bad for consumers. Clearly, messages that we do not agree with. But yet we are paying for those very messages. The First Amendment claim became a very, very big issue. It took over the case and is now being considered by the Supreme Court. This has been a long process. The litigation and mass organizing strategy The tendency in litigation strategies is to lose the power and momentum of the campaign that you just built. Everybody is just waiting to see what the court says. But we were committed to using a two-fold strategy, including continuing the mass organizing strategy. We had 23,000 hog farmers around the country who had been part of this campaign. Actively participating in this campaign to end the check-off. That's an incredible number of hog farmers. We had the list of those farmers. We had in our own states hot lists of hog farmers who would always make the phone calls on the issues related to livestock. Always contact their legislature. Come to every event that was held. It was an incredibly powerful campaign that had been built to get rid of the check-off. So, when we started the litigation strategy we were committed to continuing the organizing strategy and it paid off. During this time of litigation, we, from these same people who were part of this campaign, got the United States Senate to pass a ban on packer-ownership of livestock -- twice. That was done by livestock producers, particularly hog farmers who had been part of this campaign. In addition, we've stopped twenty factory farms in Midwestern states in the last five years with these same people. We've kept legislation from being destroyed in places like Missouri that are protecting rural communities from family farms. We have successfully kept engaged the livestock producers who have been part of this base from the get-go. At the same time, we have had some significant legal victories. The federal district court ruled in our favor -- unconstitutional. The Appeals court ruled in our favor. The USDA takes over from the NPPC The USDA then took the pork check-off to the Supreme Court and it is interesting because the National Pork Producers Council pulled out of the case at the Supreme Court level. USDA, spending taxpayer dollars, by the way, has pushed every check-off case they could to the highest level they could in the court system. And, in the case of pork, they have been the driver of taking the pork check-off to the Supreme Court. Not only did they insist on keeping it in place after producers voted it down, but they've carried it all the way to the Supreme Court to try to keep it in place. There was also a beef check-off petition. Beef producers did not get a vote to demonstrate producer satisfaction with the program, but along the way our two legal cases got on a simultaneous track. The pork case got sent to the Supreme Court and so did the beef case. The USDA participating in both. The USDA specifically asked the Supreme Court to hear the beef case and to not hear the pork case; to hold the pork case pending the outcome of the beef case. That's transpired in part because the pork case is an incredible case. It has a producer vote. It's the only commodity check-off that has ever had a producer vote in which producers voted down the check-off. On December 8, 2004, the Supreme Court heard the beef case and of course we were in a unique position because our case is specifically pending the beef case. There are a lot of check-offs now that are pending on a variety of court levels around the country; everything from the alligator check-off to dairy check-offs are all pending Supreme Court cases. But they are not all directly tied to the outcome of the beef case like the pork check-off is. How the Supreme Court rules will directly affect all the beef producers in the country, all the dairy farmers who sell culled cows, and will directly affect hog farmers who are now paying into the check-off. We feel confident that a very good case was made. (The U.S. Supreme Court has since decided against beef producers, but the final word on the hog check-off is still pending). It's a long, long road the litigation strategy and if you don't have an organizing strategy that goes with it that keeps your campaign engaged in the issues that the constituents care about, it's very hard to maintain your power and your credibility. We think that is one the Campaign for Family Farms has done well. Non-representative policymakers In Motion Magazine: You work with politicians. How well do these officials represent the people's interests in Missouri? Rhonda Perry: We work with policy makers on the issues of concern to our members and our base. We also have worked on engaging farmers and rural people into the democratic process. We obviously don't endorse any candidates. As an organization we simply engage in ensuring that the most people in farm and rural areas of our state participate in the democratic process as much as possible. Once George Bush got elected, Ann Veneman became the secretary of agriculture. As I mentioned earlier, we had just had a vote that demonstrated that the majority of producers do not favor this check-off and the first thing she does is ensure that the check-off stays in place. The second thing she does is fill the entire USDA with people who represent commodity organizations. That's been one real frustration but it's been a factor in helping farmers see who is working in our best interest here; who is putting people into (government) positions who come directly from the commodity groups that we are trying to take the money away from. Clearly, we don't feel that farmers and rural people are adequately represented with the policy makers who get into office. In part because all the policy makers, administrations, whether they are Democratic or Republican, they like these commodity groups to be in place. These commodity groups have provided intensive cover for their bad policies. They were able to say, "We represent America's hog farmers and this is what we want." "We want free trade." "We've got to open the borders." Well, you know, Democrats and Republicans alike needed that cover because the rest of the farmers were not saying that at all. There has been this temptation by both parties to enjoy the cover provided by commodity groups. There are a number of ways that we can address the non-representative nature of people who are getting into political office. One, encourage people at the local level to engage in the democratic process. And two, take out those organizations that have historically said they represented the farmer constituency to these policy makers. Take them out of the picture by de-legitimizing them. In the case of the National Pork Producers Council we have done a very good job of de-legitimizing them. It would be hard for them to go to Congress now and say "We represent America's hog farmers" when everybody knows that the majority of hog farmers voted to take away their funding. It is not as clear cut as you think to try to have representative democracy. It isn't just about participation. Sometimes it's about de-legitimizing the people who have historically been the gatekeepers for farmers. And that includes the commodity groups and the Farm Bureau. We have to continue that work as well as engaging our members and constituents in the democratic process from the county commissioners to who is going to be in the office of the president. We have to continue that fight based on the issues and the best interests of our members and constituents. Sometimes people tend to make the democratic process and participation this really easy simple thing like "turn out the vote". But in rural areas it is a lot more complicated than that. We have to take it on in a variety of levels. I think organizations like the Missouri Rural Crisis Center in other key Midwestern states are doing that and understanding representative democracy is sometimes complicated, sometimes ugly, and sometimes looks like sausage being made -- something nobody anybody ever wants to see. It's a necessity for us to participate at all levels. We are absolutely committed to doing that as part of our organizational struggle and as part of our organizational future. Commitment to organizing strategies In Motion Magazine: And that comes back to your five programs, as far as being involved in improving people's lives? Rhonda Perry: I think that people's lives have been changed and made better and made more positive. Our programs have created hope for a large number of families. I think the programs will continue to change and evolve, just like they have, based on the issues that are most important to our members and that most affect their lives. Just like they've changed since 1985 with the founding of the organization. But I think the commitment to organizing strategies won't change. Published in In Motion Magazine, January 24, 2006 Also see:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World || OneWorld / US || NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2011 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |