|

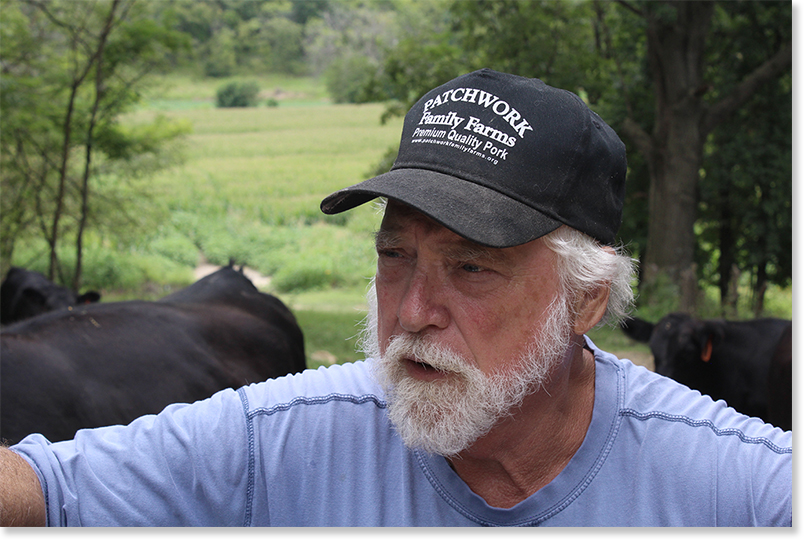

Interview with Roger Allison

Economic Sustainability in Rural Missouri Armstrong, Howard County, Missouri |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Part 1: The Economic Cost-Price Squeeze Part 1: The Economic Cost-Price Squeeze On the edge of a razor blade In Motion Magazine: What’s your assessment of how things are going in rural America, particularly rural Missouri, at this time? Roger Allison: Through this last election, for family farmers and rural Missourians, things are going backwards for us and it seems like (they are) speeding up. For farmers, input costs are extremely high and the price that we get for what we raise, whether it’s corn, soy beans, wheat, cattle, the prices continue to go down. We are on the edge of a razor blade right now and it doesn’t look like it’s going to get better for the foreseeable future. In Motion Magazine: Can you go into a bit of detail about those input costs and market prices? Roger Allison: Well, input costs mean(s) how much money comes out of my pocket to put the soy bean crop into the ground, and (that includes) working the ground, a minimum tillage, the cost of fuel, and the cost of seed. Then there’s the different chemicals that we use to control the weeds and to control viruses that a soy bean plant can get. We’ve got over $200 an acre in the soy beans right now. By the time we combine our crop (editor: referring to using a combine harvester) and pay for those expenses, we are going to have over $300 an acre in the soy beans … and soy bean prices for this fall are in the $7 range. If you raise forty bushels to the acre, which has been a fairly decent crop, that’s $280. (So,) we are already behind the eight ball … I guess you could say, (we are in) an economic cost-price squeeze where the price that we are getting is less than what it costs us to produce soy beans. And corn, the input cost for corn, the fertilizer, the herbicides, the seed, preparing the ground and then taking the crop out, is close to $400 an acre. Looking at the prices being projected for fall harvest, it’s just over $3 a bushel. … And we don’t have our crops out yet so there’s a lot of time to lose value in your crop to wind, rain, even snow if it’s an early winter. At the best, we’ll be doing break-even on a good crop. And if it’s not a good crop we will lose money again. (Also,) part of this is the trade wars that Trump has got going on with China. They used to be a large buyer of soybeans and they also bought corn. When you take out a large buyer of our corn and soy beans it spells disaster for independent family farmers. The consolidation and industrialization of agriculture In Motion Magazine: What is your assessment of the food production system in this country? Roger Allison: Well, when I came back, (editor: Roger Allison is a Vietnam War veteran) I bought a farm next to my parents’ farm, in 1975. My parents had a little over 300 acres and I was able to buy 400 acres that was right next to them. Now, most of that was financed and back then Jimmy Carter was the president and there was a resurgence of people coming back into rural areas to farm because they thought they could come back and raise a family and get a fair price. They had hope for the future. Well, since that period of time, Ronald Reagan came in and Reagan’s policy, the government policy, was foreclosure. We lost over 700,000 farmers because of that policy. And when you eliminate family farmers you eliminate these rural communities that have been service centers for family-farm-type agriculture. And so, since that period of time, this consolidation of agriculture and industrialization of agriculture has continued and picked up steam. It’s government-corporate led and independent farmers have been fighting back trying to get fair prices in the market place. Trying to get some enforcement of the Packers and Stockyards Act to break up these corporations that are controlling the livestock market. We have had some gains but, primarily, industrialization and corporatization are marching forward. That has been devastating for independent family farms in less than a generation. All these farms here in Missouri, they were primarily combination farms. They raised all the different crops, but every farm had hogs, and most farms had cattle. Through industrialization and concentration of the marketplace, led by big packers and corporations, you find very few independent hog farmers that are left. There are (mostly) farmers that are raising hogs under contract for these huge corporations. In Motion Magazine: How much of the land in this area is owned by large corporations, as opposed to independent small family farmers? Or is the imbalance that the large corporations are the only market which exists? Roger Allison: Number one, corporations are pretty smart. The farmer is owning the ground and he’s got all the expenses and they (the corporations) are selling that farmer what it takes (to farm), including the seed that’s genetically modified and patented by different corporations because the Supreme Court deemed it a new life form. In the past, farmers would hold their seed back and then re-plant and the cost would be nominal to those farmers. Land grant universities would do the research for public variety seed and the seed that was planted would improve every year, or through the years. There (was) a whole system in place for family farm agriculture. That system has been taken over by corporations. (For example,) at the University of Missouri (we’ve got) the Monsanto Building. (And) sure, Monsanto put some money in it. (But,) the researchers there are doing research for Monsanto. Taxpayers and family farmers are supporting the majority of the cost of that institution. (But yes) there is corporate ownership of land. Some of the best land. 50,000 acres in Missouri is owned by a foreign corporation that is Chinese. There is an increasing amount of ground, the very best ground, being bought by corporations but they’ve got the best of both worlds right now. The universities do the research for the corporations. The farmers buy all the inputs from those corporations. And then those corporations buy from the farmer the grain or the livestock when they are ready. They make money coming and they make money going. In some cases, farmers are just indentured servants on their own land. Trying to make enough money to pay for their family living expenses, education, health insurance. A lot of the money for independent family farmers comes from off-farm jobs where they may be working off the farm a certain amount of the time. Their wives are working off the farm. In a lot of cases it's an issue of insurance. If their wife is working for a company that provides some insurance, well, that’s insurance that they wouldn’t have if she wasn’t working off the farm. So, independent family farmers, basically, are subsidizing corporations. And that is not a good thing. Corporations, commodity associations, and the check-offs (Similarly,) we pay a check-off. For every calf that I sell, I pay them a dollar. And, when someone buys that calf from me and sells it, they get another dollar. (Then,) when that calf is sold again, they get another dollar. Again, on the beef that is imported into the United States -- they get money on beef that comes into the United States. To say that they are working in the interest of Roger Allison, a cattle producer, I know that’s not true. They work for the biggest corporations that there are. They try and relax whatever type of standards that we have in this state to ensure that the pollution from factory farms is contained. And so we are in a confrontational environment with these commodity groups that take money from us to supposedly represent us. And the Corn Growers Association, the Soy Bean Association, the Cattlemen’s Association, they are all taking money from us and then they use that money to represent the biggest of the big interests. (Anyway), we challenged the Pork Producers’ Association on their checkoff a number of years ago. We had a national vote. Independent family hog producers won that and said, “We don’t want you taking our money from us anymore because you represent factory farms instead of independent family hog producers.” And after we won that vote, National Pork Producers took us to court and they were represented by the Justice Department. We had to get our own attorneys, and pay them, and the Federal District Court found that we had won the vote. (Then) they took it to Appeals Court, and the Federal Appeals Court said that we had won the vote and the checkoff needs to be abolished. (However), then they took it to the Supreme Court -- the National Pork Producer Council with the Justice Department being the attorneys for them, plus all the other attorneys that they had using our checkoff dollars. And the Supreme Court said that it’s “government speech”. These checkoff programs weren’t just bubbled up from producers. It was what the government wanted, and it’s protected by government speech. In other words, even if you didn’t want to pay, you still had to pay. It’s sort of like if you are against war and you say, “A percentage of my money is going to war and I’m going to hold that back.” Well, you will go to jail because that’s government speech. You don’t have the right to hold your money back. These commodity groups that say, “Oh, that’s driven by independent family farmers,” that is not true. It’s driven by corporate interest, backed up by the government. There’s a large fight-back that’s going on, but they’ve got the money, they’ve got the time, they’ve got the attorneys, and it’s very hard to overcome something like that. On the pork vote, we won that, but it’s hard to get out from underneath the yoke of government-corporate-controlled domination. Part 3: Factory Farms or Patchwork Family Farms The market place for hogs In Motion Magazine: Please tell me a bit more about CAFOs. Roger Allison: Well, factory farms, that’s a CAFO (editor: Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations), factory farms are industrial agriculture owned by corporations. They stuff all these animals into tight confinement without regard to their needs. They create manure, urine, chemicals, particulate matter -- particles that are put out into the atmosphere with huge fans along with odors that have gases in them. The particulate matter and the gases have (been) proven through studies that have been done by the Center for Disease Control to be harmful to humans. And I would say, harmful to the animals that are in those buildings. Then, they dig a big hole in the ground and put all that waste into that hole. They call them lagoons. They are anything but a lagoon. There are acres and acres of big (ponds). They have a tendency to break and spill. And if you’ve got a big storm event, like water, well, it overflows the lagoons. The manure goes into the streams, contaminates the streams. Contaminates it not only for the life that is in those streams, but for any livestock, wild or domestic, that drink that water. The market place for hogs is controlled by factory farms. Patchwork Family Farms In 1992, a lot of our farmers with the Missouri Rural Crisis Center, they all raised hogs, including us on this farm. The markets were drying up. They were closing down and factory farms were coming in with no regulation. The Missouri Rural Crisis Center, we were trying to figure out a way to improve independent family farmer income. And hog prices were low, below cost of production. At first, we thought, “Maybe we could raise chickens. It would be low input and maybe we could raise family farmer income that way.” We did a study on that and then we had an economic development conference in ’92. … (At that conference,) Shirley Sherrard from the Federation of Southern Cooperatives was a keynote speaker … and one of the things she said was, “Do what you know.” We all knew hogs and it made sense that we do what we know. We came up with the name of Patchwork Family Farms because it was like the quilt Jesse Jackson had talked about his grandmother making out of rags. It was all small pieces, but by the time it was all over with it was a patchwork quilt that served their needs. Well, we were all small farmers and our farms were different sizes and in different areas, and we (all) suffered from the same issues of corporate consolidation of hogs and low prices, so we called ourselves Patchwork Family Farms. We started a process of having hogs processed and taking them directly to the consumer. We learned a tremendous amount in a short period of time and that project is still going on today. That’s a number of years later and we still learn every day something different about how to be in touch with consumers, and how to deliver them independent, family-farm-raised pork in a good manner, at a reasonable price. We have raised a lot of hogs, a lot of farmers have, and we have learned a lot about processing, and USDA inspection. We sell quite a few hogs to restaurants, to just regular consumers, and we’ve got different places where we have outlets to do that. It’s a whole system that has been set up and the goal was to ensure that family farmers always had a profit out of what they raised.. Part 4: Diversification and Adversity -- the Weather and the Climate Diversified family farms In Motion Magazine: You have a diverse variety of crops and livestock you produce. Why do people farm in that way? Roger Allison: Well, through history, family farms have always been able to stand economic bad times, weather bad times, if you are diversified. If one crop fails, you have another crop. And so, like this farm, we have 80 cows, we sell feeder calves, we raise hay, we raise wheat, and sometimes we raise oats. We raise corn and soy beans. We used to raise hogs, but we don’t have as much time to raise hogs as what we had in the past. Being diversified is healthy for the soil, healthy for the farm. It’s healthy for the ecosystem and water. It gives independent family farmers a hedge against bad times in one crop or another.. The Missouri River In Motion Magazine: Are we in the Missouri River valley here? Is this considered part of the flood plain of the Missouri River? Roger Allison: This farm? Well, no. (Chuckles.) Our farm – my dad always used to say, if we could stretch our farm out and make it flat, we’d own twice as many acres as what we do right now because we are in hill country. We have creeks and streams. We are eight miles from the Missouri River, and so, we don’t have to worry about being flooded out by the Missouri River. Our house is on top of a hill. If we got flooded out, we’ve got some serious problems. But we are not very far from the Missouri River where the flood plain is flat. Farmers have farmed it, historically, for years. This is a bad year because the levies broke. The water is at record levels and those farmers are not going to be able to raise a crop this year. I was just in the flood plains yesterday, and as far as you can drive, for a good distance, it’s weeds and water. Those farmers are going to have a pretty tough time meeting their fixed costs of production. Unusual weather patterns In Motion Magazine: Right now, around here, there’s a lot of green and you were saying this is an unusual situation – how much moisture, rain you’ve been getting. Is that a trend over the years? Do you think it has anything to do with climate change? Roger Allison: I believe that we have climate change. Now, last year we were in a major drought and when the cattle walked across our pasture it looked like Death Valley Days because there would be a cloud of dust behind them. In 2012 (also,) we had a tremendous drought. So dry that it killed oak trees that were over a hundred years old. We have seen these huge swings in weather that have adversely impacted us. It started raining after this huge drought last year. It started raining in October, and it never really stopped until April and May. And it just stopped for a short period of time. We were lucky to get our crops in. A lot of farmers didn’t get their crops in because their soil never dried out. So now we’ve got green. It’s better having green, a lush green, than it is just being dry and cattle not having a pasture to eat. But the storms are more violent. One of the biggest rains I remember was back in 1976. We had just built a pond and we had a six-inch rain. It wasn’t a common rain, at all. It washed out part of the black-top highway. It filled our pond up in just a few hours and that pond dam, even though it was brand new, it held. I could look back at that and say, “That was an event”. But now we have (storms with) four, five inches of rain every year here. That’s unusual. Even in drought times, we’ll have four or five inches of rain, and then it just turns off and bakes everything as hard as a rock. The winters have been mild except for last year, which was a very, very tough winter. Tough on farmers and tough on the livestock because it would be well below freezing and the ground was still muddy. Then it would freeze. Then it would thaw. A lot of snow, a lot of cold. An unusual weather pattern for this last winter. I hope we get back to something that isn’t as severe..So, I think that we will see what happens with Trump’s trade policy proposals, but I think we cannot afford to believe that that is the single thing that got us to this crisis mode we are in right now. We really need to look at what we are doing in agriculture and the policies we are pursuing because at this point it is very clear that they have been disastrous. We are looking at massive decreases in farm income. We have seen increases in farmer suicide. We are dealing with a significant crisis for agriculture and the subsequent crisis that that creates for rural communities. In Motion Magazine: In our conversations you have spoken of farmers getting a fair deal. What’s your idea of a fair deal? Roger Allison: A fair deal for us is a fair deal for farmers in this state and in the United States, but also around the world. We believe that every country should have the right of food self-sufficiency and that a strong independent family farm system of agriculture for this country and around the world makes the world a safer place and countries can feed themselves. (With) a corporation, they obviously know the market because they control the market. It’s sort of like getting into a poker game. If you’ve got five dollars in your pocket and somebody has got a thousand dollars in their pocket, for the most part you are going to lose that game. If you take a look (around here), there’s two huge operations. One is Smithfield, owned by the red communist Chinese, and the other one is JBS, owned by the Brazilians. They control most of the hog market and they also control a good hunk of the beef market. I think there (will be) a question of food self-sufficiency in this country at some point in time if the tables are turned more than what they are right now. If we have an extra bushel in the bin at the end of the year, the government says we have a surplus and corporations say, “Oh my God, we’ve got a surplus.” And farmers are penalized whether there is a surplus or not by lower prices – by manipulation of the marketplace. We need a different type of agricultural policy in this country that views having a warehouse or storage with commodities in it, or a certain amount of backup on our meat supply, as a good thing. Instead, it’s used for the most part to drive prices down. To extract the resources from our farms. And that, in turn, destroys the family farm system of agriculture that has served this country well. And that’s not a good thing. Family farmers with standards In Motion Magazine: When you make an arrangement between Patchwork and a farmer who wants to be a member of Patchwork, how does that deal get worked out? Roger Allison: Well, it’s pretty easy. Farmers have got to raise their hogs at standards. If a hog is sick, go ahead and treat that hog but don’t treat all the hogs. And the hogs, (they) have got to have plenty of room to roam, fresh air, sunshine. A lot of our producers raise their hogs on dirt, and they are happy pigs. The quality of the pork that we eat is better. It tastes better. It doesn’t smell. If you take a factory farm hog, you go to the store and buy the meat, you put it in a pan with a little bit of water and you cover it, and put it on a low temperature, get it to steaming, and then you lift that lid and you smell it -- what you smell is shit because those animals can never get away from all those gases and smells that they are in in total confinement. (As far as prices go), -- the price goes around seventy cents a pound. Some farmers get a little more if their hogs yield more for us. But it’s basically right around that area. Now, all prices have been up for a little, but they’ve been down and we’ve still been able to maintain that price and be competitive for a locally raised product raised by independent family farmers with standards. (We have) a producer agreement that has those standards in it and that producer agreement also has a membership fee to Patchwork Family Farms for $50 a year. A very reasonable way to get access. Organic produce: a direct relationship with the consumer In Motion Magazine: What do you think about organic produce, the organic labelling system? Roger Allison: We have farmers that raise produce organically and we have had farmers that have raised soybeans organically. I think that on the vegetable end of it, through the different types of small markets that are out there, you have a direct relationship with the consumer. I think that that is good. (But,) I see that there are always those trying to reduce the standards and still call it organic. Like using toxic waste from these factory farms in these chicken buildings as fertilizer and then still being able to call your product organic, organically raised. So, there are fights that go on around the organic label (in which) the producers are trying to make sure that when a consumer eats something that says organic it truly is. There always (are), and I say always, corporate interests that import vegetables into the United States that are trying to lower the standards and still call it organic because consumers in the United States and around the world are looking at what they eat, and they want something that they feel is good and safe for them and for their family, and they are willing to pay a little bit more money for it. Corporations are jumping on the band wagon and trying to water down the organic standards so that they can then flood the market. That’s a fight that will continue. Sustainable agriculture In Motion Magazine: What do you think of the idea of sustainability? Roger Allison: What we are trying to do is be sustainable. Just like this farm here. We are trying to sustain it and then pass it along. It’s very damn tough. It’s very hard to do that. That’s one form of sustainability. Sustainability (has) meant how things are raised and how you view what you are doing. But sustainability is being co-opted by big monied interests to the point it really doesn’t mean anything. “Oh, this is raised sustainably.” “Right. What do you mean by that?” “Well, it’s just raised sustainably.” Where people believe in sustainability there’s a whole value around sustainability. The corporations that are trying to exploit sustainability have absolutely no value system other than money. It’s (the same with) organic and sustainability -- those fights are basically one and the same. Trying to maintain what those values are. But one of the things I’ve always said about sustainability, if we are talking straight up sustainability, you cannot have a sustainable agriculture unless there’s a profit for independent family farmers. If there’s no profit to pay for the farmer’s livelihood, that’s not sustainable. Sustainability has to have a profit margin in it for independent producers in order for anything to be sustainable. Economic sustainability In Motion Magazine: A lot of people are leaving the countryside, so they say, and going to cities. Big cities. Do you think it would be good for not only the people that were rural and left, but even for people that grew up in the cities, to start spreading around more? Living more in the countryside. What would it take, in your mind, to do that? Roger Allison: It would take economic sustainability in order to do that. It’s no big secret about why these rural areas are depopulated and that is because there’s no economic sustainability here. The corporations have sucked out every penny. You’ve got to have income to raise a family. And the secret is to have an agriculture system that’s a family farm agricultural system and these monopolies need to be broken up. There’s no reason why we shouldn’t be raising hogs on a large scale out here. Every farm having a few hogs instead of corporations just having hogs. That would mean breaking up the market forces that have industrialized and vertically integrated the hog market. What they are trying to do right now is to take the cattle market. We’ve got eighty cows out here, but they want to take those cows and their babies and put them underneath a roof, put them in a confinement building and raise cattle that way. That is the push with the Cattlemen’s National Association and the Missouri Cattlemen’s Association. They want to see that industrialization. It means more power to them. It means more money to them. But what it means for these rural areas out here is devastation. We are going in the wrong direction. We need to be going in a direction where independent family farmers are making a fair profit out here and that takes some proper government intervention. And we have just not seen that, frankly, since I’ve been farming. That’s 1975. (Coming back to rural areas) is a wonderful concept but it takes gas to get to town and go to a job and if you live forty-five minutes away there’s gas, wear and tear on the car or a truck, and the job that’s in town most of the time is not a high-paying job. We’ve got a lot of space for people to come into but there’s got to be an economic incentive for that to happen. It’s not going to happen just out of the blue. It’s got to be everybody is getting a fair shake out here. If family farmers are making money and there are more markets, then that bubbles up throughout the economy. It’s not trickle down that does it. Farmers and rural people are in an economic minority. < Economic and social justice for all of us > In Motion Magazine: Is there anything else you’d like to say? Roger Allison: Well, things are bad and it’s not wrong being a pessimist about where we’re at at this point. But, at the same time there is hope, the hope that we can come together as a people and demand fairness and fight for each other’s rights. And that has occurred throughout history. I truly believe that even though these systems are completely out of whack with big money, big corporations that care nothing about anybody other than the bottom-line and them building another house in some other country and taking advantage of those people that live in other countries – their labor and natural resources of the area. I truly believe that we are coming together. We can fight for justice, economic and social justice for all of us. That’s how we are going to win, and we will win.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Published in In Motion Magazine April 11, 2020 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2017 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |