|

Interview with Rhonda Perry

Local Control or the Corporatizing of Rural America Armstrong, Howard County, Missouri |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

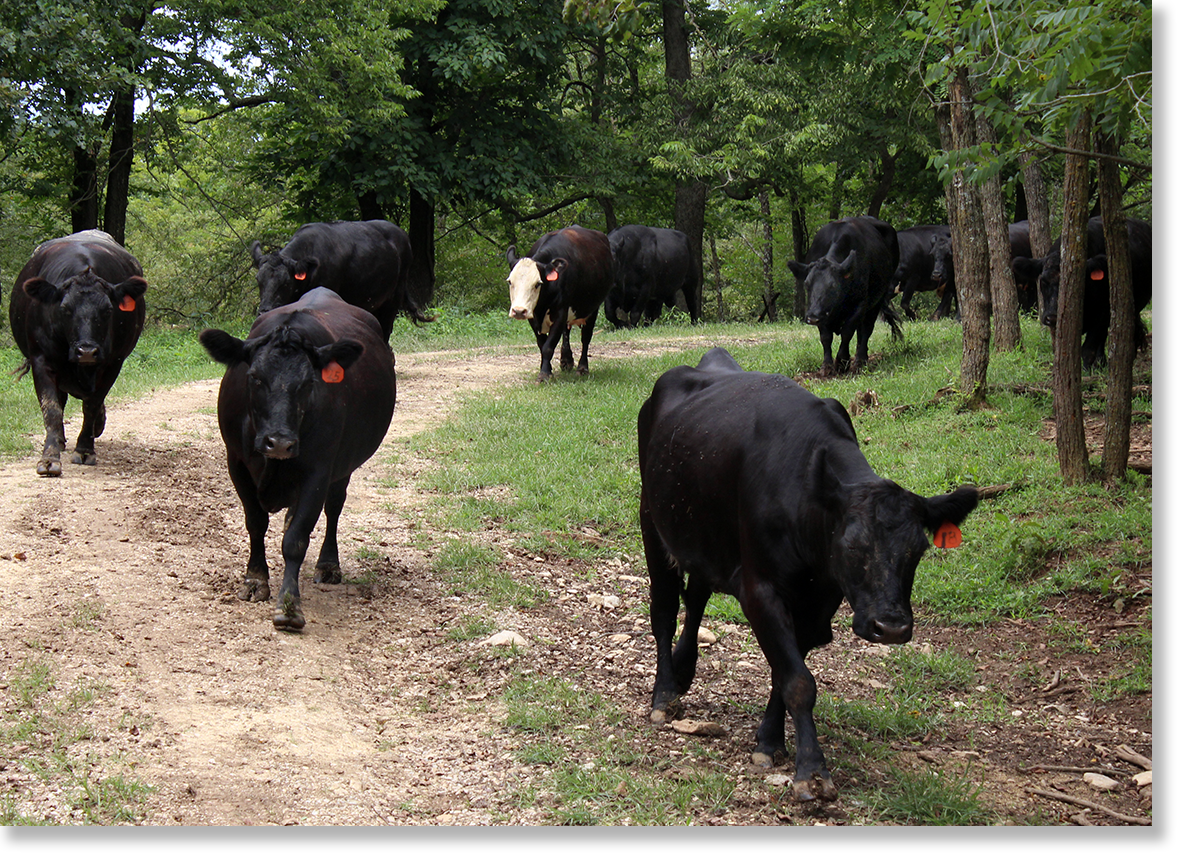

Part 1: The Missouri Rural Crisis Center Part 1: The Missouri Rural Crisis Center All issues related to family farmers In Motion Magazine: Could you please describe the Missouri Rural Crisis Center? Rhonda Perry: The Missouri Rural Crisis Center is a statewide farm and rural membership organization. We work on issues related to food, agriculture, rural economies, rural communities, rural healthcare. Really, all issues that are related to family farmers. The Missouri Rural Crisis Center mission is to preserve family farms, promote stewardship of the land and environmental integrity, and work for economic and social justice for all, including building unity and mutual understanding among diverse groups, both urban and rural. In Motion Magazine: How is the membership going? Rhonda Perry: We have about fifty-six hundred member families. Some are organized in chapters. Some are at-large members. We have individual members. We have family memberships. Then, we have chapters that make up our food cooperative program. And of course, we have committees and leadership teams that help us feed from the ground up -- from the communities in which people live into the policies that we work on as an organization. Federal policy, factory farms, healthcare, a food cooperative In Motion Magazine: What is the primary focus of MRCC at this time? Rhonda Perry: We continue to have some long-standing programs that we have had for literally decades. And then we have some new programs. One program area is federal farm policy, which includes federal Farm Bills and policies, trade policies, and food policies. We have a factory farm organizing program which is both about challenging corporatization of agriculture, specifically the livestock industry, and then, also, about what are the solutions to that, in terms of governance at the local level and the rules of the road that we think are important to have in place to protect communities from corporate livestock operations, and the health and environmental problems that they cause. One of our other programs is about rural healthcare. That’s a program in which we work to highlight the specific challenges related to rural Missourians -- rural Americans in general, but specifically rural Missourians. In particular, a lot of people don’t understand that rural people tend to be older, sicker, and poorer than our urban counterparts. So, (the program concerns) our ability to talk about how rural healthcare affects the economy, access to healthcare, and the policies that we need in order to make rural communities healthier and better prepared to be able to meet their needs. We also run a food cooperative program which we’ve had since 1986. That program serves about 400 limited-resource families every month, which demonstrates the need of people, (even though) they live in rural communities and they are farmers and they produce the food for the country. There are a lot of challenges related to hunger for rural people, including lack of access to fresh fruit, vegetables, produce, any kind of healthy food. Just like there are food deserts in urban areas, there are long-standing historical food deserts in rural areas, as well. Unfortunately, that has had to be a long-standing program of ours. But, fortunately, (the cooperative) has been there, (and) it has grown. We have a big volunteer base that helps make that happen. Patchwork Family Farms, Growing the Local Food Chain We also have a project called Patchwork Family Farms that markets sustainably-raised pork in mid-Missouri and St. Louis and all over the country, for mail order. That’s a project that started in 1993 in order to address the fact that we could see that the corporatization of the hog industry was going to result in fewer and fewer farmers, less access to markets, less access of consumers to high quality pork that was raised sustainably. And, then, we have a program called Growing The Local Food Chain, which is a project that is all about local food, but it is also all about bringing youth into the local food system -- bringing youth from St. Louis and urban areas together with youth from rural Missouri in order to learn how to grow food and figure out what their role is in the local food system. People think that to be part of the local food system you either have to be a farmer or a consumer, but there are so many places in the food system that people can engage, from being a farmer, to a producer, to a marketer, to a retailer, to restaurants and grocery stores, and to ultimately being a good consumer. There’s a lot of work around trying to create the next generation of people who understand and care about food. We use that program to break down barriers related to geography, related to race, related to class. So, that has quickly become an important program, an ongoing program for us. Rural Voices Project, Black Rural Organizing Project (There are, finally) two other projects that are happening right now, which are both very exciting. One of them is our Transformative Conversation Program, which we are currently naming our Rural Voices Project. That is a program about having conversations with rural people about what are the core issues that are affecting their lives and their communities. What do they think the solutions are? We are digging deeper than I think most conversations go, trying to find out who people think is at fault for the situations that we face in rural America. And what do they think the solutions can be? That’s a super exciting project that we are hopeful is going to both tell us what people really think, and what the narrative is that they use and that they will respond to. And the other exciting project that is already moving into becoming a program of ours is what we have been calling our Black Rural Organizing Project. That is about ways that we can work to defeat racism and address not just racism but a lot of the isms that keep us separated - particularly people of color communities in St Louis and rural Missourians. We started (that project) in April of 2018. It’s grown and we are excited. If it was easy, we would have already done it. We know there are going to be challenges but we think we’ve come a long way already and we are in it for the long fight. It’s going to be a program that we are happy to engage in. In Motion Magazine: Can you talk about the local control program? Rhonda Perry: Local control is at the core of a lot of the programs that we do, from the on-the-ground programs that we have meeting the needs of people to our policy programs. Local control specifically has been a primary focus for us as it relates to agriculture in rural communities. From the inception, since the ’90s, we have been heavily engaged in trying to protect local control and the local communities’ ability to make decisions about what kind of agriculture they want. What kind of food system they want in their communities. And, to make sure the communities have tools to protect themselves from the environmental and health and economic devastation of these corporate industrial factory farms and livestock operations. (These operations) are not primarily managed or controlled by people who live in our communities, but they tend to be controlled by people, or entities, corporations not people, who are out-of-state and even foreign corporations. The battle has been long, and it has been hard, (but) it has been incredibly rewarding. It has created big opportunities for people in our organization to go from being people who stand up in their local communities to being leaders of our organization. There are intense challenges because the opposition that we are up against, they are the biggest of the big. They are the multinational corporations who want to control all of agriculture. It has become increasingly important for local communities to be able to stand up and fight for their communities and for the health and environment in their communities. Sheer power and mistruths In Motion Magazine: Local control seems to have become more of a focus in the last two or three years. What has happened? Rhonda Perry: It’s interesting. We have had this local control fight in the legislature every year since 2003, except for 2006. That’s a lot of years that we have had to defend the ability of communities to have those rights. (But) in the last three years, it has been intense fights and the opposition (has become) not just corporate agriculture and multinational corporations, and even just straight up foreign corporations, but also organizations who act as their mouthpieces and their lobbyists, including the Farm Bureau, and all the commodity groups who get our money. (Regarding these commodity groups,) we don’t volunteer to give them our money, but they have mandatory programs through the government that ensure that for every bushel of corn we sell, every head of cattle we sell, every head of hog we sell, there is a checkoff that forces us to contribute to those programs that we do not agree with. (Editor: e.g. the mandatory commodity checkoff program of the National Pork Board, a program sponsored by the USDA's Agricultural Marketing Service.) And those programs endorse, support, and promote the corporatization of agriculture. (So,) because those entities they have a lot of money, they do the bidding for corporate agriculture and we have recently had a new governor who is very much in that camp of promoting the corporatization of agriculture and they do it with sheer power and mistruths. I would say just basic lies about who is going to benefit from corporate agriculture. And it’s not going to be family farmers. And it is not going to be consumers. And it is not going to be anybody who works in between in agriculture. We have seen the people who really push this system of agriculture. They like to say this is the wave of the future. “This is what is economically sound. These operations are environmentally sound. It’s inevitable. This is what our future is. It’s going to be great for farmers. Great for consumers. Great for workers.” And what we have seen is exactly the opposite of that. We have lost ninety percent of the hog farmers It’s pretty interesting because we don’t have to guess at what the corporatization of an industry would look like. We have the hog industry that in one generation has gone from having thousands and thousands of producers to being almost completely corporatized and industrialized. In Missouri, we have lost ninety percent of the hog farmers in our state in one generation. Now, some people would say, maybe we are more efficient now. Maybe we do it better. Maybe we do it more effectively. But the price of pork has gone up over a hundred percent. All of those businesses that rely on independent family farm production do not exist anymore. The producer’s share of every retail dollar has drastically decreased. And, we went from thousands of farmers who had control of an industry, where we had lots of markets to sell to, to having virtually no markets to sell into. And now two foreign corporations control fifty percent of an entire U.S., supposedly American, agricultural industry. Smithfield in China and JBS in Brazil. And, really, a substantial part of the hog market, over sixty percent, is controlled by just four corporations. But almost fifty percent of it is controlled by just two foreign corporations. And certainly those family farmers who raised hogs for a living and made good money didn’t benefit from that. Consumers now have higher prices. They don’t trust how their food is produced. They believe that the pork that they know about is not pork the way that they would want it to be raised. And we have local economies that are in shambles. So, what we are looking at are multi-faceted challenges, but also multi-faceted solutions that we have to have. What we have to be about is trying to protect things like the cattle industry from going in this direction. That’s ultimately super important in a state like Missouri. Missouri has the second largest number of farms of any state in the country, after only Texas. We have 53,000 cattle operations in our state. That is really a substantial number of family farmers. And the family farm operations work in Missouri because they’ve been diversified for a long time. We raise row crops. We have hay. We have pasture. We have cattle. That’s an important piece of our economy. If we lose the cattle industry like we did the hog industry, we are going to be up a creek. So, our fight is both for the environment and the health of the people who live here and it’s also for the economy and for the existence of independent family farm livestock producers. An outright attack on local democracy In Motion Magazine: What’s the story of Missouri Senate Bill 391? Rhonda Perry: Well, this year in the legislature, literally all of the commodity groups and the Farm Bureau decided to pass a bill that would take away local control. Historically, in Missouri, counties had the ability to pass health ordinances. Meaning, they could put in place protections from these kinds of operations that are totally unaccountable to the communities in which they operate. They tend not to be from here. They tend to be out of state. They tend to be foreign corporations. And some of them who are even U.S. corporations, not in Missouri, but U.S. corporations, they also raise hogs in China. They have zero allegiance to our country, to our communities, to our food system. And so, in Missouri, counties have always had the right to pass those ordinances. We have twenty health ordinances in rural communities in our state. Those have been critically important for the protection of our natural resources and the health of people who live here. It was one of the last key ways, it was the bottom line, that we had to protect ourselves. And the legislature determined that they wanted to get rid of that. Really, not the legislature, (but) the corporations and the entities who act on their behalf and lobby on their behalf. Out in the countryside in Missouri, local control is not a partisan issue. It is not a Democrat issue. It is not a Republican issue. It is an issue that people believe in. Thousands and thousands, tens of thousands of contacts were made with legislators. Thousands of Missourians weighed in to stop Senate Bill 391 which takes away local control. And yet ultimately, in the end, the governor and the Republicans in the legislature, the rural legislators in the legislature, sold out to corporate agribusiness and corporate lobbyists at the expense of independent family farmers and at the expense of rural communities. And, at the expense of the basic notion that people should be able to have access to their government at the most local level possible. I think there is an incredible amount of energy and pushback from that. There is a lot of momentum right now and a desire to hold those people accountable. We have had four public meetings in just the last month, and we have had seventy people, eighty people, a hundred people who are turning out for these meetings and who are speaking up. I think it’s going to be critical that we continue to do that. But I also think that sometimes people who live in cities -- we all make generalizations about what city people are like and what rural people are like -- one of the things that is true, is that when you stand up in rural communities you have no anonymity. When people stand up in a rural community for something they believe in, like local control, or protecting the health of their community, or the water of their community, that takes a lot of guts. It's an incredibly powerful thing when people do that – and people are doing it every single day. And it’s going to matter. I think our role is to help people do that. Help give people a voice, to have a say, both at the local level and at the state level. I think ultimately people are going to be a lot more engaged on this issue than they even have been for the last twenty years because of this outright attack on local democracy. The Howard County health ordinance In Motion Magazine: You were talking in a conversation we had about a health ordinance that you struggled on in this county. Can you talk about that? Rhonda Perry: Yes. So, here in Howard County we have never had a CAFO. (And), I think, one other thing to note is the difference between Iowa and Missouri, when it comes to local control. A neighboring state, Iowa, lost the ability to have local control in the ’90s and they now have over 10,000 CAFOs and over 700 polluted waterways. People in rural communities have to fight every day just to be able to open their windows and be able to breathe. The Des Moines Water Works has paid millions of dollars to clean the water, just for people to drink in Des Moines, because of the incredible amount of pollution -- a great deal of which has been caused by these factory farms and CAFOs. In Missouri we have 500 CAFOs. We have less than one half of one percent of the farming operations, CAFOs, in our state, yet the legislature has insisted on representing this very small but powerful minority of corporate agribusiness at the expense of the rest of agriculture. Here in Howard County, which is a prime example, we have never had a CAFO. (And) in 2017 a 7,900-head sow operation was proposed for our county. It is an out-of-state corporation. They have targeted Howard County, Cooper County, Chariton County, Saline County. They are targeting central Missouri. But when they targeted Howard County people fought back. People stood up. And it didn’t matter if you were a Republican or a Democrat or an independent, it mattered that people had made big investments in their lives here in Howard County. They own property. They own land. They have taken care of the water and the air. People really stood up in our county to fight back against this CAFO. And our county commissioners (did) put in a health ordinance. All a health ordinance does – it is what you would think of, and what I would think of – as very common-sense protections of the water and air for the people who live here, for the protection of natural resources, which includes pretty basic set-backs for (the) spraying of millions of gallons of waste. Setbacks of these CAFOs from people’s houses, from water, from public water systems – from the very basic things that we know we need to protect in order to have a future that has clean water and clean air. It was powerful to see how people from all areas of the county stood up and talked very honestly with our county commissioners about why having a health ordinance was important. And our county commissioners did pass the ordinance in April of 2017. And it did stop this CAFO. 250,000 pounds of dead animals The sad thing was (then I’m going to come back to the happy thing), the same corporation, Pipestone (https://www.pipestonesystem.com/), has at their address in Pipestone, Minnesota, fifty-two LLCs (editor: Limited Liability Corporations) registered at that location. They are a company which either manages or owns tens of thousands of sows in China. They are an entity that when they proposed their CAFO in Cooper County, the county next door, when they could not get into Howard County, their waste of just sheer hog shit was going to be 8.6 million gallons a year. They were going to generate 250,000 pounds of dead animals that were going to be in open-air sheds. That’s a quarter-of-a-million pounds of dead animals just rotting in a local community. The amount of waste and the amount of pollution that was created by these operations is incredible. And (additionally,) they had the ability to do something called, being an “export-only operation,” which at that time had no rules on how you could apply it. There was no DNR (Department of Natural Resources) rules at all at the state level for the application of millions of gallons of waste in an export-only operation. And, unfortunately, in Missouri we have had such watered-down laws that you could build a CAFO with thousands of head of cattle without even having a construction permit. For years that has been the rule. There are no air quality standards at all in the state of Missouri for DNR for any operation that is less than a Class 1A which is 17,500 hogs. For any operation less than that there are no air quality standards. So, unfortunately, when these operations can’t go in one county, they move on to the next county and they try to go there. Fortunately, (however,) Cooper County just last week passed a health ordinance through their Health Board, so hopefully they will be able to stop this operation from coming in there as well. But in Howard County -- back to the good news -- the county commissioners put in place the ordinance. It is very common sense. It did not affect a single-family farm which currently farms in Howard County, but it would impact these corporate agriculture businesses who want to put in thousands and thousands of heads of animals in concentrated and confined operations. So, the commissioners passed it and they said they wanted to put it on the ballot in August of 2018, which they did. And, last year, in August of 2018, there was a vote in our county. It was very contentious. One thing it is safe to say, is our opposition on this and those who represent corporate interests, they don’t always necessarily always feel compelled to tell the truth about what the impacts are. But people in this county were incredibly committed and we passed the ordinance. The vote was fifty-eight (percent) to forty-two. People voted for the ordinance in every single precinct. And this is a very rural county. We totally rely on agriculture. We have an incredible number of livestock farmers here, and farmers were the key leaders at making sure that this ordinance was kept in place. So far, we are protected by that ordinance and twenty other counties have an ordinance. We hope that in the future people can continue to make this a key priority and speak out on this. And the counties that do not have ordinances, I think they are going to join us and fight like hell to make sure that they maintain the authority to pass these ordinances. Next year is 2020, next year is a new year, and I think that legislators are going to hear from people in places like Howard County. Now, not all counties have a vote, but in Howard County a vote of the people was had. A vote of the people was clear. And to take away that vote of the people, to replace it with the voices of corporate agriculture and their lobbyists, would be a crime. Why we need local control In Motion Magazine: Could local control be improved? Is the problem simply the state legislature? Rhonda Perry: We believe that the current ordinances are protected because they were in place before the law (SB391) was passed. I think there will probably be a law suit that will determine whether or not this law was constitutional, and whether or not communities will maintain the right to pass these ordinances. But I think it was a chance for people in rural Missouri to clearly see that the people who are representing them, the people that they elected to office at the state level, do not have their best interests at heart. And, that they one-hundred percent caved to the pressure and the power of corporate agriculture. What that means is all that does for people out here is demonstrate why we need local control. Why people have to have access to government at the local level where there haven’t been corporate lobbyists, where we have actually been able to have access. You can talk to your county commissioner any time. Not only do they have office hours, you see them in the community, you have access to those people. Clearly, people have not been having access to their state representatives. They have not had the opportunity to make sure that they heard what they were saying because, seriously, the number of corporate lobbyists for agriculture is absolutely incredible. In the last four weeks of the legislative session, just to make sure that they passed this bill, they hired seven new lobbyists. It was one of the most disgusting examples of the extent that corporate ag, and the organizations that represent them, will go to to get rid of local control. They understand just like we understand that that is the place where people have access to try to protect themselves and their community. So, we will see what the future looks like in terms of local control. But what we know and what we can tell from the hundreds of people who have engaged in this campaign since the legislative session, is that it is a core issue. It is an issue that people feel in their gut and they are incredibly disgusted by what has happened. I think ultimately that is going to make people think about local control in an even bigger and more present way in their lives every day. And, based on what we are seeing, people are going to be willing to stand up. Long, multiple, horrible Farm Bills and unaccountability In Motion Magazine: How does the Trump trade war fit in to this – or does it? Rhonda Perry: Right now, we are in a time of significant economic challenges in rural America, agriculture in particular. It isn’t just the trade wars. It isn’t just Trump’s policies related to agriculture and tariffs. It is long, multiple, horrible Farm Bills that have created policies that are just about massive over-production and (there has been) no way to actually ensure that there is any economically viable market structure in place. Just the way we talked earlier about the pork industry, that could be the future of a lot of agricultural industries. Once we are at the point that we don’t have markets (in which) to sell our products, and we don’t have functioning markets, and we don’t have competitive markets, we are going to be seeing even worse economic devastation than we see right now. But this year, in particular, is an incredibly harsh year for family farmers. Like I said, the Trump policies are one piece of it, but the other piece of it has been a serious un-accountability of elected representatives at the federal level to stand up for the importance of independent family farmers and fair markets. They have been representing pretty non-stop for decades the interests of corporate agriculture. They did not put in place any anti-trust laws. And I will say that the Obama administration, who came into office as a change agent, who said they were going to ensure there were open and competitive markets, and they held meetings around the country with the USDA and the Department of Justice – (well,) literally tens of thousands of family farmers believed that they were going to make change and that they were going to ensure that there was not this complete monopoly in agriculture. And they went to those meetings. They left their farms and their communities, and they paid on their own dime to go to those meetings. And then the Obama administration figured out what kind of power multinational, corporate ag organizations and entities have -- and they caved. That’s the same power that people out here in rural communities have been up against and are fighting every single day. (But) the Obama administration, they did not get that. When the power was put upon them, they did not do what family farmers and rural people have been doing. They did not stand up to those corporate interests. And you can tell. Thus, people were not very excited about their agricultural policies. And, frankly, they (the Obama administration) did not take on corporate ag in a big way. Now, neither did the presidents before Obama in recent history, either. But I think people thought something different was going to happen and that did not happen. And then, when Donald Trump ran and said that he was going to change trade policy -- I don’t know if this is what people thought he had in mind when they voted for him (laughs) -- but I can say that where we are today in agriculture did not happen overnight. It didn’t happen in the last six months. It happened because people who have been elected to represent us in Congress, in the Senate, in the White House, they have not done their job and they have totally caved to what amounts to an extremely powerful group of corporate interests in this country and multinationally. I would say that right now we are in a situation where net farm income has decreased by thirty percent since 2013. We have a concerning cattle market right now. We have cattle imports. We stopped, we got rid of country-of-origin labeling. The same organizations who we just talked about, (who) lobbied hard to get rid of local control, lobbied just as hard to get rid of country-of-origin labelling. All of the tools that we have to protect agriculture and family farmers and food, nationally, at the state level, and locally, are under attack by corporate agriculture and their interests. So, I think that we will see what happens with Trump’s trade policy proposals, but I think we cannot afford to believe that that is the single thing that got us to this crisis mode we are in right now. We really need to look at what we are doing in agriculture and the policies we are pursuing because at this point it is very clear that they have been disastrous. We are looking at massive decreases in farm income. We have seen increases in farmer suicide. We are dealing with a significant crisis for agriculture and the subsequent crisis that that creates for rural communities. In Motion Magazine: What does sustainability mean to you? Rhonda Perry: Sustainability. Sometimes when people say that, or when people who I don’t think really believe in it talk about it, they mean one specific thing about sustainability. I think when we talk about sustainability we have to mean the ability of communities to sustain themselves economically; for the food system to be able to sustain itself and its existence with something that is not just corporate mass-produced food; and we have to mean the sustainability of our natural resources to be here in the future and to provide for people in the future. I think farmers understand sustainability. We understand it as our ability to sustain what we have. And that’s why people who live in these rural communities and who are independent family farmers are willing to fight so hard and for so long because we know that once we lose that ability to protect our economies and our natural resources for the future, we may not be able to get it back. We are not going to get back the hog industry. Once we lose the control of agriculture out of the hands of thousands, and hundreds of thousands of farmers, and worldwide millions of farmers, once that’s not who’s in control anymore, it impacts not just the environment and our water and our air and the economies of rural communities, it impacts our democracy, which also we have to think about when we think about sustainability. We have to be able to believe that we are going to sustain our ability to have a voice in the democratic process. I think right now all of those things are in question. Our ability to know we are going to have access to good food that we can choose how it was raised. That we are going to know that we have access to clean water and natural resources. That we are going to have access to the democratic process, which is less and less true. (And), this issue of local control is one that seems to make people think about sustainability in all of those arenas. Not just the traditional “sustainable agriculture,” but about a sustainable and hopefully improved democracy. To protect this system of agriculture In Motion Magazine: You were saying in an earlier conversation that some people are starting to notice that in the earlier stages of the MRCC the issue was the government, now that is different. Can you talk about that? Rhonda Perry: We are facing this economically challenging time in agriculture, but some people think -- and I hope this doesn’t turn out to be true, but it looks like it very well could be – it ends up looking very similar to the 1980s farm crisis. Hopefully, we learned some things about what works and what doesn’t, and the role of government, and the role of corporate agriculture. And we are going to be able to take action before we get as far in as we were in the 1980s. But I think there are a lot of similarities. That was a tragic situation that forced, illegally, hundreds of thousands of family farmers off their farms, and we can’t afford for that to happen again. But the interesting thing that is sort of different, that has changed over the last generation, is that then it was actually the government who was illegally foreclosing on family farmers. It was the government who was acting with absolutely no due process. And, through the actions of thousands and thousands of family farmers in Missouri and around the country we did things like people went to federal court to try to protect their land. And those court cases resulted in class action lawsuits that stopped illegal farm foreclosures. And we passed the 1987 Credit Act that said very simple things like the government cannot illegally foreclose on family farmers without providing due process. Things that you just think the government should already be doing, but they were not doing it. It was a time that farmers were fighting back. But at that point it was about the government because that’s who held the notes, that’s who held the loans. Now, we’ve come to a time where the government has significantly abdicated their responsibility to even protect food security, the future of agriculture. To protect the system of agriculture that can feed us into the future. They have succumbed to the power of corporate ag. Now what we see who we have to fight against are these corporations who are trying to come to our communities and pollute our water and our air. And people are standing up to that. But, you know, we also need our government to play a role in ensuring that we do not have the same kind of crisis that we had in the 1980s. And play a role in ensuring that we are protecting the health and the welfare of the people who live in our counties, and in our state, and in our country. The issue of food security is so incredibly huge, and to have elected representatives at all levels that feel no obligation to ensure that we protect this system of agriculture that has served us well, and that has ensured that a state like Missouri can have a hundred thousand family farms who make a living in part because of agriculture -- it’s really ridiculous. But it does clearly demonstrate the role and the power that these corporate food and ag companies have on our democratic process. We need to go about the business of not just standing up to these corporations directly but standing up to the government who has not been protecting us, and who has been selling out rural America. People believe in rural America In Motion Magazine: I have learned over the past years that there are a lot of people moving out of rural areas into big cities, which personally I feel are proving themselves to be failed projects in and of themselves. What would it take to encourage people to come back to the countryside? Do you think that is a desirable thing? Rhonda Perry: I think it’s definitely a desirable thing. I think that most people who live in rural communities would like to live in rural communities. (But) there are a lot of things that would have to happen for people to be able to stay here in rural communities. I think we need to look at what the challenges are first. Farmers aren’t getting paid a fair price for what they produce because we do not have open and fair competitive markets. We do not have a system that enables farmers to make a decent living farming. Right now, we have seriously record low prices in agriculture. We also have consistently had trade agreements that have shipped good jobs overseas and that have ensured that agriculture was not the beneficiary. That we are opening up our borders to increased imports in a lot of arenas. We do not have good access to healthcare. A lot of states in rural areas who have not passed Medicaid expansion are seeing major, major hospital closings and significant loss of the ability to have good jobs. When you have an agriculture policy that does not pay farmers a fair price. When you have trade policies that ensure that any good jobs that we used to be able to have in rural Missouri and rural America are now shipped overseas. When you destroy the infrastructure of things like healthcare and the food system by corporatizing it -- you are going to see exactly what we have now, which, as we talked about with the hog industry, (is) why we are fighting so hard not to let that happen with other industries in agriculture. When we lost that ninety percent of the hog farmers, twenty-two thousand hog farmers, I believe, out of business in Missouri in one generation -- all of those businesses that relied on that industry are gone. And, when they are gone, and people don’t have jobs, it doesn’t just matter because the people don’t have jobs, it matters because then we don’t have people who are engaged in our schools, in our churches, in our communities, in our social organizations. And that’s what keeps rural communities together and keeps rural communities strong -- as well as the economics. So, I think we are facing a pretty serious crisis in rural America. We have a lot of challenges. We don’t have decent Internet. We live far away from things. People frequently in rural Missouri travel two hours to go to any kind of specialist doctor at all, or to a hospital in a lot of cases. We know there are a lot of challenges in our school system, which we do not adequately fund in any way, shape, or form. We have a lot of challenges but when you ask people, “Where would you want to live?” so many people who grew up in rural Missouri would rather live in rural Missouri. They would rather live here, work here, farm here, raise their kids here, have their jobs here. People believe in rural America. They think that it can be and should be able to be made up of people who are committed to their communities and who can make a decent living. If those things were here, they would be here. Somebody just asked me the other day, when we held a listening session … . We were going around the room asking people in the room who were nurses and teachers and farmers, “What do you like best about living in rural Missouri?” And, of course, I said, “Everything.” (But) some people said, “community.” It was the number one thing people said. It was community and their ability to have access to talk to their neighbors, to the power that comes from being able to be part of a community. Then a lot of people said, “The access to nature and the open space and to farms.” That was a powerful moment where we had just spent a half an hour talking about all the challenges in rural Missouri related to factory farms and local control, and access to healthcare, and access to the Internet, and the travel, and the space that it takes to get from one place to another place. Then, when asked, “What do you like most about rural Missouri?” people didn’t have to think about it for even one second. Their response was so incredible. It was about community and it was about access to the environment and natural resources in our state that are everywhere in Missouri. Missouri is an incredible state. That’s who needs to be determining the solutions I think everybody in that room was super committed to living in rural Missouri and to not just talk about the challenges but to talk about the solutions. The thing is, people who live in rural Missouri and rural America, that’s who needs to be determining the solutions. We are smart and we know our communities, and if we have real access to the democratic process and our voices can be heard, we are going to be able to make rural America work. But if we stay on this system where we let people outside of our communities continue to have a larger voice than we have about our communities, we should expect to face these same kinds of challenges in the future. The one thing about rural Missourians, and I think rural people everywhere, is that they will fight to protect their communities, as can be seen in these fights in Missouri around local control. People will stand up at incredible risk to themselves and their families and even their own economic livelihood because our economic livelihoods are all intertwined with each other’s. And, when you stand up in a rural community you are risking a lot. (As I said,) there’s no anonymity. The same people who may think they are going to benefit from corporate agriculture are the same people who are going to be in your Sunday school class. They are the same people who are going to be bringing you food when you are sick. Who are going to take care of your cows whenever you are in the hospital. When people stand up, it’s big. It means shit. I think that was one of the things that came up in our conversation in this same listening session that is on my mind right now – how incredible and powerful it was, but also how brave people are. The other thing -- since I am on this listening session -- we had a little conversation about what people thought that people in urban areas maybe didn’t understand about rural America. And one of the things that people thought right off was they didn’t understand the space that people have to go to get to things and to even participate in both their healthcare or the food system or democracy, and the kind of commitment it takes to do that. I think everybody agreed that that was true and then everybody proceeded to agree that everyone in that room and everybody they knew was so committed that those challenges were not going to be insurmountable. That was a really incredible conversation that was had. I think that we want to make sure that we have more of those kinds of conversations, where people can voice what they love about their rural community and what the challenges are and what they think the solutions are -- because I think those are going to be the solutions.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Published in In Motion Magazine February 22, 2020 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2017 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |