|

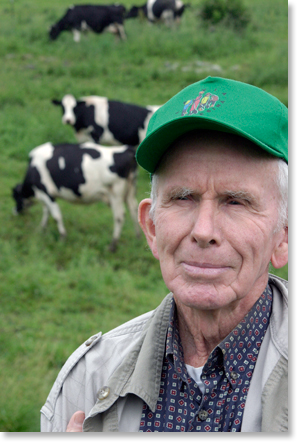

John Kinsman is, “ ... a small organic dairy and forestry farmer in Sauk County in the hills of southwestern Wisconsin. I am one of the founders of the Family Farm Defenders, (www.familyfarmers.org) which is an international organization based in our capital, Madison, and presently serve as its president. In addition to being a member of several other organizations, I also serve as secretary of the executive boards of both the National Family Farm Coalition (NFFC) (www.nffc.net); and the Midwest Organic Dairy Producers Association.” The interview was conducted (and later edited) by Nic Paget-Clarke for In Motion Magazine on June 24, 2011 on the John and Jean Kinsman farm, near Lime Ridge, Wisconsin..

Dairy: A right mixture of clover and grasses

In Motion Magazine: Please talk a little about your farm.

John Kinsman: My farm is a farm that my wife and I bought about 54 years ago. It was a run-down farm and we could afford to buy it. A widow had lived here many years, a very kind woman who was our neighbor. It was so run-down, there were places that not even weeds could grow. It had been rented out. People would pay so much to rent the land and take the crop off and no organic matter was ever put back for many, many years. The buildings had not had any paint. Nothing fixed. But it was very reasonable.

It was probably the best thing that happened, as I look back, because I learned to be frugal. Of course, I lived through the Depression, the Great Depression, and my father, if we did not have enough money to buy flour, he would take some wheat out of the bin and we would have it ground and we’d have whole wheat bread, which we hated and now it is a delicacy. My mother had a hundred chickens and that was really the only thing that she had to feed us and clothe us. Just the income from the eggs, because the rest went back to my grandmother, who was still alive, to pay for the farm.

The farm supports thirty-six milk cows and twenty-eight younger cattle and it is all in grass and hay. In other words, pasture and hay. It’s intensive rotational grazing. Every twelve hours, we move the fence so that the cows have new pasture. We are able to use some of the second-crop hay and third-crop for pasture by dividing with temporary fences. We buy no protein. You were in the barn and you saw that they did not need protein, from the way that the manure was. People say that that is impossible, but it is not impossible. I’ve been organic for almost fifty years and the soil rebuilds itself. Many of the hay fields regenerate a population of a right mixture of clover and grasses. Of course, nitrogen comes from the legumes and complements the grass and sometimes I was too busy being involved in Civil Rights works and others and would neglect, but the neglect paid off.

One of our most valuable bi-products

We have a very low input, as far as buying things, especially oil-based products. No herbicides, no pesticides. The only fertilizer is a rock phosphate, a natural phosphate that we add to the manure for every load and that balances the mineral content of the manure and it locks up the nitrogen that would be lost otherwise. That is our total fertilizer. I call it one of our most valuable bi-products -- the manure. In these large CAFOs and large farms, it is animal waste. But I maintain anytime animal manure fertilizer is labelled animal waste, that entity has too many cows, or too many pigs, or too many chickens because that is what built up this farm. Now, people say, “Oh, sure your crops look good,” or my “hay looks good, because it is rich land.” They don’t remember how it looked. All the rocks sticking out. Parts of it, pastures and hayfields, we call it stonehenge, big rocks sticking out. Some of them five-foot tall, or more. But, by rotationally grazing it and giving it a rest between, we are getting up to ten times more grass and milk off those areas.

And then, the hay fields, we don’t raise any corn. We buy a little organic corn to keep the cows in condition, but it’s very small, so we have very low input as far as machinery. My total machinery investment is probably $16-17,000. My neighbors sometimes put in that much for one plow or one small piece of equipment. We don’t have to go over our land all the time and pack it down because we don’t have to keep re-doing the planting.

Agro-forestry

Then, my other passion is forestry. Forty acres of forest land that is in hardwood forest trees. When we bought that, the neighbors said, “Oh that’s your most level land. You’ve got to bulldoze down those trees and plant corn.” I don’t want to do that. It’s beautiful. There’s young trees in there. Nice trees. A lot of maple trees. A lot of oak trees, cherry trees. So, I had a local forester look at it, and he said, “You can buy land cheaper than you can bulldoze it if you want to plant corn, you can buy land cheaper than you can bulldoze that one. You’ve got a lot of potential here by doing timber stand improvement, which is management practice.” First of all, you keep the animals out of the woods because they pack down the soil so it doesn’t bring the tree roots to the surface by the packing. The cattle get very little good out of a forest unless it’s agro-forestry, the right conditions, the right types of trees, but not the type that we have. Trees will grow up to six times faster by cutting off the diseased, the weed trees. Some trees, like ironwood, are out there that are a hundred years old and yet they are four inches in diameter. They are very dense, the leaves, so the other trees don’t come up. So, you take them out, excellent firewood because they are hard. They are called ironwood for some reason, anyway.

And then we managed this. We have more than enough of the wood that should be taken out of there to heat our house. We have a wood furnace. And then, there were steep side hills that were nothing but rocks and a little bit of brush. That’s where the cows pastured and they got nothing out of it, except excercise. So, we planted, I can’t remember how many thousand, in that area, on those steep side hills. That was fifty-six years ago. Some of those trees are now eighty-foot tall and they are two feet in diameter, some of them. If I had thinned them properly. ... I didn’t thin them properly because they were all so straight I didn’t want to cut off those straight trees. But now we have to do another thinning.

I had a friend and a neighbor, an Amish man, Kenny Yoder, who thinned them several years ago, and he was able, just from the thinning, to sell it for pulp. Get a little return and still have the job done.

Again, it needs thinning. But that land was my least valuable land, now it is probably my most valuable. It’s just beautiful. You can’t see the rocks. The needles and the leaves, the vegetation have covered up all of them, practically, that were on those side-hills. And, when it rains, these heavy rains, it’s like a sponge. It soaks it up. Then, I will have fresh water for maybe a month after a heavy rain where there never was a spring or water before. That’s in the cow pasture below.

A Conservation Reserve

So, the forestry part. We planted some other land -- my sons and daughters, four of us -- land was that almost being abandoned, but was being sold because it had worn out from too much corn, too rough, never should have been cleared in the first place. Steep. We were able to buy that and put some of it in the CRP (Conservation Reserve Program) and plant trees. We probably planted 100,000 trees altogether in my family.

My oldest son bought this land 35 years ago and we planted trees. I owned a quarter of some of it and sold it to his son -- they are actually harvesting some trees for pulp (because you have to take out half the trees, of course.) He will be able to have ripe logs in 30 more years. (A ripe log is one that is not going to grow much more. It may have some dead limbs in the top, and you can tell by the root exposure they are not going to do much. Then it’s time to cut them for lumber, to sell for lumber.) So, it’s like money in the bank, sustaining on a tree. It’s a tremendous resource and it’s the best use of this type of land. It’s the highest and best use.

So, I have no more land to plant trees. I have to be content to thin and, like I say, some of the pine and some of the spruce are so big that now some of them should be cut. In fact, an Amish schoolhouse was built from lumber here. Together we picked out trees.

In this case, it was white oak, big old trees that needed to be cut. We picked out the right ones and we said, “Well, you can have those.” And so, two days later, I went by where the school house was to be built, and it was already up. I thought, “They must have got the lumber somewhere else.” But they didn’t. They went in and cut and with the horses pulled it out, sawed it up, and two days after they had looked at it, it was a building. It was just amazing. It’s just down the road. You came by it when you came in here.

You can do little sales like that for extra income. But it’s getting to the point, and I have, that some of the trees have to go. It’s a low-input operation, taking care of them. Winter months, also. They regenerate if you take the right trees out and leave the young ones there. There’s wild life. There’s turkeys. There’s deer, and hawks, and owls, which we never saw (before). There’s eagles, now, nesting in different places. Never saw them except near the river. It’s very interesting to see what can happen.

Intensive gardening

In Motion Magazine: How about your garden? How does that fit into your life?

John Kinsman: Well, my grandmothers and my mother were great gardeners. We had a huge garden and we lived off the garden and the chickens. And, of course, we had pigs too. So, we had pork, beef, chicken, and then you had all the garden stuff. They only bought salt and sugar, basically, and maybe some flour.

It’s a satisfying thing to do. I used to have a larger garden when our family was home but they are all gone, and most are married, and many of the grandchildren are married. So, my grandkids, and my kids, always say, “Grandpa, don’t sell the farm.” They come here and enjoy it. Just now, on two sides of the house, I plant using intensive gardening methods. The only fertilizer is some compost made with cow manure -- dry cow manure piled behind the shed. And my kids and grandkids come with bags and put them in their cars and take them to their gardens. And the people, my youngest daughter especially, says, “The neighbors just marvel, ‘What kind of fertilizer did you use. You’ve got such a beautiful garden?’ ‘Just my Dad’s manure.’” -- which is composted.

Anyway, our local group sponsored a speaker, a young man that came to a food fair we put on. And he was so excited about the people who came to the food fair and who showed what they were raising, gave samples, one was yogurt. Everything they had, they showed what they produced, and there was almost enough for a month. And he said, “Can I come and give a presentation on the lasagna garden?” He was just so excited about doing this. He does it for schools. And he came to the LaValle library, we sponsored him, and we were talking about it, and Lee, who had just moved in the area with her husband. We were discussing where we should have it, she said, “We could have it at the library. I am the librarian in LaValle.” So, great. She advertised, very extensively, and there were no chairs left in the police department or the fire department, they had so many people come they had to take all the chairs in the neighborhood.

It was a lasagna garden, where you laid out heavy cardboard. And he had pictures of before and after. And then, you put layers of straw or hay and leaves, and maybe some dry manure -- that’s the lasagna, the different layers. But, if you’ve got all hay, there’s enough nitrogen. You don’t need anything else. Put it two foot deep. And let it there over winter, or six weeks in the spring. Then, you plant directly in it and there’s no weeds. It’s great for schools because they plant it before the students leave so that when they come back in the fall it’s all ready to harvest, pretty much, Not much (weeding) in the summer, almost five minutes of weeding all summer. And the small seeds, you put a little furrow in the mulch, there, of soil, and plant the seeds -- carrots, radishes, whatever you want, or lettuce. As it grows, you have to weed that a little bit. Then, you bring the mulch up.

(Laughs) There was a tremendous rush on cardboard the day after the presentation. One woman said, “I called the appliance store and I said, ‘Save the cardboard because I’m coming in at a certain time.’ ” She went to get it, and he said, “Oh, was it you?” He said, “Another woman came in. I thought it was her and I gave it all to her.” And it was one of the other women that were part of the group. (Laughs)

Fair Trade Neighborhood

Our group has been working together for two years now, our local Fair Trade Neighborhood, we call it, of urban and rural who never have talked to each other before. Never knew the others existed. And some of the urban people didn’t know that there were farmers raising organic pastured beef and pastured chicken, and strawberries, everything.

We thought, to get things going, the best way to get people to work together, was to put on a free meal. There’s a monthly free meal at one of the Lutheran churches in Reedsburg, and its free. Everybody can come but its mainly aimed at the disadvantaged, socially and economically, people. So we said, “We will do it.” And I said, “We’ll have to make it all local.” “Oh, it’s impossible. The snow is three feet deep.” It was early February -- we were planning this three years ago. So, David piped up, “I’ve got carrots, but I have to find out whereabouts they are, because they are under two feet of snow.” Then, we got organic beef from Steve Ihde. We got squash from Mary Ellen McCluskey, it was in storage. And Melvin Troyer had onions and potatoes in storage. The nearby orchard had extra apples. Omer had cabbage in storage. And my wife and my daughter made the applesauce from the apples. Everything was local. The snow, it was the last day of February, it was cold, snow, and it was the best meal they ever had.

We had enough money to pay the people by donations and we’d ask David and Omer and Melvin “How much?’ and they’d say, “So much for the potatoes.” And then Marilyn, my daughter, knows prices because she and her husband own a delicatessen, so, when you’d buy ingredients, she’d say, “That’s not enough. That’s not fair trade.”

We would pay them what fair trade was and they were just amazed. And, almost always, we had to pay them ... they weren’t even asking for cost of production. They were asking what they always had to sell for. People are always bidding against one other. This competition game. All these local growers. And not any of them were making a living, just selling vegetables and fruit. They all had to do something else. But their passion was to produce food. Most of these farmers were dairy farmers at one time, the Amish and the others.

And so we got this mixture. It started out in four Catholic churches. We challenged the Peace and Justice Committee to do something. And food was the most unjust ingredient because it is being bought and sold, traded on the stock exchanges to the lowest bidder. And then sold to the highest bidder. When that happened, in the ’80s, I think Goldman Sachs started it: international poverty, starvation skyrocketed, and producers were pushed off the farms in record numbers. All over the world.

Trading in commodities

In Motion Magazine: Because of what?

John Kinsman: The trading in commodities, buying and selling grains, and cheese, and all this.

We have gone to the Chicago Mercantile Exchange in Chicago for about the last six years, on the International Day of Peasant Struggle, to do our part because we have had people research this. A farmer from the East has done a great job, using their figures to show whenever Kraft or whatever, DFA (Dairy Farms of America), which is a big dairy cooperative and very oppressive, they decide how much profit they want in that quarter. What they decide is the price of cheese, which determines the price of milk, and then, from Chicago, that price goes to Europe, to the European Union. And from there it goes all over the world. It is always the lowest.

And we knew all of this and we went inside and got an appointment so we could be in during the trading. We sent certain people in. The rest of us stayed out and handed out leaflets. The traders thought, ‘Oh, here’s this dumb bunch of farmers.” They were smiling, joking around a little bit. The smiles disappeared when we knew their inside jokes. They were betting how they could set the price of cheese under five minutes.

Sometimes there’s only one there. Sometimes it’s Kraft, sometimes its Kraft and DFA. Now, there’s other subsidiaries that they’ve bought up. Their names are there. There’s no such thing as supply and demand setting prices.

So, that was how we tried to educate people. And now we have a chapter of Family Farm Defenders in Chicago of people who heard about it by email or on the Internet and came to support us.

Also, starting a year ago, we’ve come to the point to getting this good food into institutions. ... One hospital in the county. Amy Miller was very helpful. She was interested. She was already doing some local foods in that hospital and the menu was as good as any restaurant around. Pastured beef. She showed a color picture of hamburger and described what it was. And the chicken. And the vegetables. Now we are talking to four hospitals and one school. We have already made some shipments to her hospital.

But the point is, like one man who made a question last night said, it’s democracy in action. I handed out the Seven Principles of Food Sovereignty (link to new page) after the first meeting. We meet once a month and we sponsor these different events -- dinners. ...

And (as I said,) we are insisting that the church meals be all local. We are not saying they have to be certified organic because we are going above the organic standards. We are meeting the social and human standards of treating people with a fair price, which the organic standards do not even address, at all. That is very interesting. They know what the price is going to be. They know how much certain people want -- and we are doing this. We have an alternate market.

Both locally and globally

In Motion Magazine: You do a lot of work representing both the NFFC and Family Farm Defenders working with La Vía Campesina (http://www.viacampesina.org/en/). Please talk about the relationship between that kind of work and this work in Sauk County.

John Kinsman: (There is a saying, that) you have to act locally and think globally. We at the Family Farm Defenders always said you have to act and think both locally and globally. What I saw working with La Via Campesina since it began, working with Paul (Nicholson) (http://www.inmotionmagazine.com/global/p_nicholson_int.html) and Nico and those others in Europe, 26, 27 years ago, and José Bové, it had to be, we have to do both. There’s no question.

Everyone was facing the same thing and, supposedly, by edict and propaganda of the corporate world, we are all enemies of each other. We are competing, just like the Check-Off Boards. (Such as) “Pork is the other white meat.” They should be working together. They are spending hundreds of millions of dollars to fight each other. They should be cooperating. And, meantime, the people administering those programs are getting rich.

Anyway, when the first WTO (World Trade Organization) events were happening, we went to Seattle. Jose Bove and I led marches. He said, “You’ve got to walk with me” because I was the one he knew the best. We served our cheese from our fair trade cheese factory, and he served his sheep cheese and his wine in front of the McDonald’s in Seattle.

And, there were so many reporters at that event serving the cheese and wine in front of McDonald’s, they were pushing him into the McDonald’s. Right up against the window. I thought, “If he breaks the window, by the force of them all trying to get his picture, we’re done. (So,) John Nichols is a wiry guy. I said, “John, get in there and get him out of there.” And he did. He went and pulled him out. And we moved on. I had to keep him moving because behind us were the anarchists who were breaking windows and the police allowed them to do that. It was very obvious to us because we were at the front. And so we kept ahead of the tear gas and the whole legions of men on horseback. Policemen on motorcycles. And then, there would be others with all their riot gear and shouting behind us. It was just bedlam. We went all the way down to Pike’s Place down at the waterfront, the big market. And there we did talks and different things.

La Vía Campesina

In Motion Magazine: Do the connections go both ways?

John Kinsman: Yes. What we learned, over all the years, we developed the concept of food sovereignty, (Editor’s note: the Seven Principles of Food Sovereignty) and first of all with Via Campesina. I saw all of that happening with Nico and Paul and the others. I was at many of the meetings. I was at the one in Havana (Cuba). Different places. Porto Alegre (Brazil). Whenever there was a big event we always had a meeting. We had a lot of night meetings in Seattle. We’d meet wherever we could. Paul would translate for me. And in all those events that lead up (to creating the concept of food sovereignty,) it all related to your local.

And, at the same time, the NFFC has the Washington office, which is in the Methodist Building on the right side of the Supreme Court building, facing the capitol -- it’s in the belly of the beast. We knew that’s not the answer because we have been there too many times. All these promises by all these politicians and their aides -- the next day or the next week, they broke all the promises they made to us. That’s not the answer. But you have to inform them.

We learned from the hundreds of years of experience in Europe, from all their struggles and from working with them and meeting with them and drinking with them, we knew that was the wrong way to do things. Any time you destroy the rural economy, the entire economy will collapse. And they said it takes hundreds of years to recover. We learned that in all these communities in Europe and Africa and Asia, South and Central America, especially the MST (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra - Landless Rural Workers' Movement / http://www.inmotionmagazine.com/global/gf_mst_int.html ) -- unless we did it locally, it’s never going to happen nationally. And even if it did happen nationally, it wouldn’t be sustained because the local wouldn’t be in place to make it stay that way.

Consensus and the Seven Principles

So, then, we started organizing. Knowing the local people, and all the propaganda they are fed in 90% of the press, I thought, “This is going to be impossible.” But I used the Principles of Food Sovereignty. We got buying and selling, putting on these meals, and paying a fair price, and telling them, “You are not asking enough.”

And I still have to do that. David, a while ago, gave me some money for gas. He said, “You talk about fair trade, it’s about time you took something.” He insisted paying me for gas. Very generously. At first, I refused. I thought, “That’s wrong.” But, we are doing what we are told to do. Pay people a fair price for what is going on.

(It’s) like when we handed out the Principles last night. I noticed that all of our people picked them up and read them again. That's the third time they have got those over a period of two years. What is amazing to them is that everything is included and that is why I say, “Everything is there. You don’t have to make up any more rules. Any more regulations. Any more goals. everything is included in those Seven Principles and nobody can argue with that.”

And so they are starting to use them, especially the social part of it. Like I say, we are working together. ... It’s cooperation, that is the answer. And, to use the experiences of the Via Campesina over the years of coming to decisions that are unanimous. Consensus. They don’t pass any of these rules with three, four hundred people there, if there’s any objections. They go on until everybody agrees. That’s why it takes us some time. The Indians do that lots of times. As do other Indigenous people. That’s why it is so powerful. You are not competing or turning someone off. If there’s someone who is really out to make trouble, they weed themselves out in a group like that. ...

A fair trade price

But, the best part is to understand a fair trade price. (Otherwise) they get what’s left, all the producers. Farmers, everybody gets what’s left. It starts at the top. The corporate take all they want. All the middlemen, all the processors, everybody, and what’s left the producer gets. If there’s any left. And it is always below the cost of production.

In Motion Magazine: What is a fair trade price?

John Kinsman: A fair trade price is cost of production plus enough profit to live in dignity.

|