| "... identity is memory, identity is vision, ..." Forging the Sound of the New Millennium Interview by Chris Gonzalez Clarke Los Angeles, California

The art of Quetzal is also highly political. Heavily influenced by the Zapatista rebels in Chiapas, where the band traveled for an encuentro last summer, Quetzal espouses the notion that we must create our own spheres of social, political and cultural autonomy in order to be free. Their work articulates a vision of what unites people in struggle throughout the world. The following interview by Chris Gonzalez Clarke with Jose Quetzal Flores, the band's spiritual and musical leader (though he'd never call himself that) was conducted in December 1998. During a lengthy phone conversation they talked about the band's self-titled debut CD, Zapatismo, and art. Below is some of what he had to say. Chris Gonzalez Clarke: A lot of your music has an explicit political message. Can you talk about how you view the connection between art and politics? Jose Quetzal Flores: It's got a lot to do with history, and looking at the relationship between different artists and social movements. And how arts played a role and were integral to every revolutionary movement that has existed. ... A good example is the Mexican muralist, Siquieros, because he was able to do it more openly. Siquieros was jailed but at least he didn't have his hands cut off like Victor Jara (Chilean troubadour). So, in that sense he was working at a time and place that allowed him to express his political sentiments. When you analyze who (these revolutionary) artists are talking to, or taking inspiration from, you feel a sense of relationship as opposed to people who paint flowers or the Mona Lisa; that doesn't say anything to me. It's bourgeoise, upper class privileged art. Siquieros cared deeply about humanity and injustice world wide; that was his world. He understood that if you make art accessible, it can impact the world.

Chris Gonzalez Clarke: How do you apply the concepts of Zapatismo on this side of the border, in the context of your desire to be a successful band? Jose Quetzal Flores: While it would be nice to be a big "success," whatever that is, and to sell a bunch of records, at what expense are we willing to do this? I believe there's a slow, natural process of getting your music out there, and building audience support. It's one that allows the artist to remain in touch, and address issues that concern you, and to have the time to address them through action, that's critical -- to act. Chris Gonzalez Clarke: I've heard the great Chicano artist Malaquias Montoya lament the fact that, as movement bands began to move from folk and acoustic music to dance music, much of the political content and focus was lost. Instead of quiet coffee-house type gigs, where the attention was on the music and message, the audience began to focus on one another, who they were going to dance with, getting another beer, etc. Your band plays dance music yet you are able to maintain a great deal of interaction with the audience. What are your thoughts about this?

Tylana and Martha are no joke. They are real musicians with talent who are blowing people away and have something to say. Plus the whole East LA scene is into the mode of making a conscious effort to acknowledge the struggle of women and for us as men to act on that as well. Chris Gonzalez Clarke: Talk about the song "Pasa Montañas." Jose Quetzal Flores: It's about the intersection of Chicanos, Indigenous people and Mexican immigrants. The pasamontañas is the garb that the Zapatistas wear to pass through the mountains. It's for physical protection and it's symbolic because under the mask are men, women, children who are all Zapatistas, so the mask represents this common struggle that unites all these people. The song is talking about the common vision that we share, it's talking about arriving at that place where we as human beings can work with dignity, create with dignity and can dialogue productively. I'm trying to explain what ties us together, and how we can make hope out of it. I'm also talking about myself, the rejection I've experienced related to my identity; claiming my identity and in the process shedding negative experiences. Chris Gonzalez Clarke: The song seems to be talking about the concept of Aztlan. How relevant is that concept today, in a very multi-ethnic Los Angeles?

Chris Gonzalez Clarke: Now that I hear you talk about your music, it seems clear that the theme of identity is very central to you and the group. Jose Quetzal Flores: Dealing with issues of identity is the essence of why we exist. In order for neoliberalism to grow and for imperialism to become neoliberalism, there needed to be an absence of identity throughout the world. ... identity is memory, identity is vision, identity is confidence, identity is positive reinforcement. It's the foundation by which some of us can grow, create and facilitate our own lives. It's the past, present and the future. The need for someone to feel important and valid, to say I exist, I'm not just a number or something. My uncle just got out of jail, after having served four years in solitary, years in prison -- most of his young adult life. And yet his sense of identity is so strong that he doesn't let this get him down. He's out now, and he's moving on, he doesn't worry about what happened in the past. He sees himself as a person with a future, you know. Chris Gonzalez Clarke is president of Son Del Barrio Music and a member of Los Otros. Also see:

This CD is available from the In Motion Magazine store. |

| Published in In Motion Magazine March 27, 1999. |

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2020 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

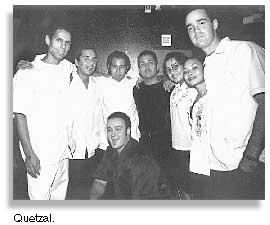

The eight members of Quetzal are pioneers of the new Chicano Groove, a burgeoning Los Angeles-based music scene that has produced popular groups such as Ozomatli and Yeska and who's roots include Los Lobos, the Latin Playboys and the Chicano rock sounds of the 70's. For these U.S. raised barrio musicians, influences from both sides of the border are readily assimilated. Quetzal's lyrics of barrio life and dreams in Spanish and English reflect the agility of Ruben Blades, poetic touch; their devotion to the groove is reminiscent of P-Funk; and their synthesis of a wide range of styles invites comparisons to Mexico's Cafe Tacuba.

The eight members of Quetzal are pioneers of the new Chicano Groove, a burgeoning Los Angeles-based music scene that has produced popular groups such as Ozomatli and Yeska and who's roots include Los Lobos, the Latin Playboys and the Chicano rock sounds of the 70's. For these U.S. raised barrio musicians, influences from both sides of the border are readily assimilated. Quetzal's lyrics of barrio life and dreams in Spanish and English reflect the agility of Ruben Blades, poetic touch; their devotion to the groove is reminiscent of P-Funk; and their synthesis of a wide range of styles invites comparisons to Mexico's Cafe Tacuba. I've always felt the importance of this idea (connecting art with social activism) but I didn't know how to begin, and then there was the Zapatista uprising in 1994. I started reading the communiques from the EZLN, and they were poetry! Their communiques quoted the Popol Vuh, Malcolm X, Victor Jara and presented their ideas in a way that was accessible and made sense. At that time I was so hungry for a vision, that it was natural for me to eat this up and personalize their message, that was key.

I've always felt the importance of this idea (connecting art with social activism) but I didn't know how to begin, and then there was the Zapatista uprising in 1994. I started reading the communiques from the EZLN, and they were poetry! Their communiques quoted the Popol Vuh, Malcolm X, Victor Jara and presented their ideas in a way that was accessible and made sense. At that time I was so hungry for a vision, that it was natural for me to eat this up and personalize their message, that was key. Jose Quetzal Flores: What makes Quetzal different is the female factor. Both Martha (Gonzalez) and Tylana (Enomoto) have tremendous stage presence, they're no joke! They demand your attention. Also, both onstage and offstage the energy of the two women, creating in the same space with men, enhances the sensitivity of the group. It's not that sensitivity is the sole domain of women or that all women are inherently sensitive, but as men we're so socialized that we have a problem with emotion and communicating, especially with other men, on an emotional level. So it's easier to communicate on an artistic level, an emotional level with women. And the audience recognizes that and responds to it.

Jose Quetzal Flores: What makes Quetzal different is the female factor. Both Martha (Gonzalez) and Tylana (Enomoto) have tremendous stage presence, they're no joke! They demand your attention. Also, both onstage and offstage the energy of the two women, creating in the same space with men, enhances the sensitivity of the group. It's not that sensitivity is the sole domain of women or that all women are inherently sensitive, but as men we're so socialized that we have a problem with emotion and communicating, especially with other men, on an emotional level. So it's easier to communicate on an artistic level, an emotional level with women. And the audience recognizes that and responds to it. Jose Quetzal Flores: The concept of Aztlan has changed a little. It's a spiritual safe haven, the place I travel to in my dreams and find comfort and relax for a minute, you know? It's just a model, the one that we have right now. If other people of color want to take that model and build something bigger and more beautiful that would be great for me -- I'd follow it.

Jose Quetzal Flores: The concept of Aztlan has changed a little. It's a spiritual safe haven, the place I travel to in my dreams and find comfort and relax for a minute, you know? It's just a model, the one that we have right now. If other people of color want to take that model and build something bigger and more beautiful that would be great for me -- I'd follow it.