|

A Conversation with

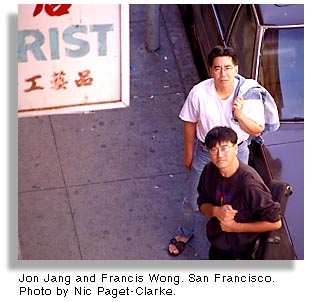

Jon Jang and Francis Wong 10th Anniversary of Asian Improv Part 4 - We want to bring our culture to people in our music San Francisco, California

|

| The music-making process

In Motion Magazine: Things don't go in a linear manner, and music is the least likely to do that, but stepping back from music in the 20th century where do you see yourself in the musical spectrum? Francis Wong: I'm basically playing myself at this point. In a sense that's why it's not linear. It's important not to look at things linearly. It implies that the next thing down the line is better. I think it's important to stay away from that. Artists like John Coltrane and later on folks like David Murray and Julius Hemphill were basically inspiring us to play ourselves. To master as much of the tradition as we can but to take it in a personal direction. That's what the 20th century is like. Even if you look at classical music. There's certain styles that framed things, but when you get to the 20th century, or at least the mid-20th century, people are themselves - whether it's Varese or any one else. After serialism people don't really analyze music in terms of styles. In the late 20th century we have a lot of influences we can draw on, to take materials and see how they fulfill a personal vision. In Motion Magazine: Is your approach in any way definable, other than saying go out and listen to the record? Francis Wong: I'm interested in process. The music-making process. For me, primarily, in a performance. How do musical ideas come to me? How do I process them and create music? You've heard the term being "in-the-moment." Being able to be in-the-moment, to be in touch with my own history and experiences, and also to be in the present and play whatever I feel like at the moment - that's the process I'm interested in. I don't codify my stuff. Take that performance last night (at the Theater Artaud in San Francisco). I'm thinking, I'm going to play for these people. What do I want to do? Well, I figure I've been playing the national anthem these days because that's how I'm making my statement about being American. It's how I play the national anthem. So I went out and I started out by playing the national anthem. Then, what else do I want? Well, I want to play God Bless the Child, because I'm concerned about those things. I feel those things in society. It's putting those aspects together - programming my experience, processing in the music-making event. Certain influences came through when I played: Jimi Hendrix, Sonny Rollins, Billie Holiday. Plus I kept returning to the national anthem. A lot of that is about the contradictions ofAmerican life as a person of color. I ended by playing Amazing Grace, dealing with the spiritual. Ending on that was important. That's one part of my body of work - improvising, while drawing on different materials. Another thing that I'm aware of is that not too many people have seen a Chinese American play the saxophone, or play anything besides classical music. I'm conscious about that in some situations when I walk out there. What's this guy going to do? I've gone on in situations where people don't think Asian Americans can play this music, or any music. It's about making that personal statement. Still, in this society today, when I walk out into a room of white people, or whoever, they haven't heard very much from us as Asian Americans. They haven't seen us do very many things. How do I do that in a way that is not didactic that I feel is expressing myself? It's bringing together traditions. An art genesis Jon Jang: I scored a silent film from the revolutionary epic period of the Soviet Union during the 1920s, when Eisenstein was producing, a film called the Arsenal, by a Ukrainian filmmaker named Aleksandr Dovchenko. That movement has been described as an art genesis . It isn't that there's a movement and that art is defined by the movement, but the art defines the movement and it's always changing. Genesis is always transforming, and I think what Francis is saying is that we are always changing. Jon Jang: I scored a silent film from the revolutionary epic period of the Soviet Union during the 1920s, when Eisenstein was producing, a film called the Arsenal, by a Ukrainian filmmaker named Aleksandr Dovchenko. That movement has been described as an art genesis . It isn't that there's a movement and that art is defined by the movement, but the art defines the movement and it's always changing. Genesis is always transforming, and I think what Francis is saying is that we are always changing.

The Asian American Creative Music Movement or Asian American Jazz Movement is sometimes looked upon as a commodity. For example, we're doing this Big Band Behind Barbed Wires and for me even though Reparations Now is not exactly a popular hit, I wouldn't want to do it again unless we could do it differently. When we're playing music we always want to keep it alive and fresh. It can't just be this broken record. If you look at other artists like John Coltrane, he went though a period in the 1950s playing the blues, playing modal pieces. Then he started recontextualizing standard materials, a lot of which was informed by Asian and African traditions. After that he developed his music into multi-sectional extended forms. I also look at what was happening inside of ColtraneAside from looking at Coltrane's music artistically, the composition analysis of those works. I also look at what was happening inside of Coltrane as he was becoming more religious and making a commitment towards God. You have to remember that Coltrane passed away when he was forty years old. And according to Hale Smith who wrote the liner notes to my Two Flowers on a Stem, and who knew Coltrane, he said Coltrane was still searching, just like Eric Dolphy. In our life we know who we are in terms of our personal expression but I think it's always going to be this searching and self examination. Particularly, now that I'm in my forties, I see that we're at this cross-roads where we have our parents who will be leaving us and we have our children. We're learning both from our parents and from our children. That also informs our music. We want to bring our culture to people in our musicFrancis Wong: A lot of times, interviewers want to know the stylistic thing, how to put the music in a bag so that people will buy it. But how we want to express ourselves in our own context in our own vehicle is more about how we want to bring our culture to people in our music. We want to bring a sense of the complexities and subtleties and contradictions of that culture. By saying our culture is not Chinese culture, it's the culture that we've come up with. It's a very specific set of experiences. I personally want to be able to represent that. I think that's why oftentimes my work is not that easily categorized. It's about the culture that I come from. I think that's also the challenge to the listener. It's not like you can listen to it and just like that you can get it. I want to have people over time get a sense of what that culture is that I come from. There's a sense of a work in progress. I'm still putting things together. I may change the way I put it together tomorrow, what I put together yesterday. I suppose that is a long way of saying 'well you have to listen to it.' The musical process is a form of storytelling ...Unfortunately there are people who don't seem to have time to listen Jon Jang: I think what 's enjoyable about the musical process is that it's a form of story telling. What's always making it interesting is it is connected to our own Chinese culture. My family, my grandparents are storytellers, great story tellers. Our music is not literate, we're telling it differently. But we also are telling the story. Unfortunately there are people who don't seem to have time to listen.. They want to know the end of the story. This is superficial like films which are about sex and violence, about effects, or something else. The visual artist Ruth Asawa says, 'We have to go back to the fundamental value of learning how to grow a garden.' It takes time, allowing it to process, to grow in its own way. It has its own tempo. The most superficial is when people say 'oh yeah I read about you.' Or,when I'm getting an award my bio gets changed because what I think is meaningful, they don't think is meaningful. Some say, 'oh yeah you're a jazz pianist'. Well they are not familiar with my works. I certainly don't give jazz piano concerts. The unfortunate thing is that people will not be able to experience fully what we do. They are already trying to put the music into a different system, instead of allowing it to affect them, or transform them. When I first listened to John Coltrane's My Favorite Things it had a profound impact on me. But later on, as I got to listen to it more, and as I developed more as an artist, I was able to hear other things, not only on a technical level. I appreciated it on a deeper level. We are artists all the time, not just in our concerts, or in our recordingsFrancis Wong: We are artists all the time, not just in our concerts, or in our recordings. We form a musical culture, a web of relationships. Jon and Joyce had their anniversary dinner so they brought their daughter over to stay at my house. When Julie and I had our anniversary we take our children to Jon and Joyce's house. To get the full experience means recognizing our works not just in terms of the musical commodity. The work gets commoditized when it comes down to the record or the concert ticket. But this is not paying attention to what we try to do in our lives, as artists. What we do doesn't come down to just playing those notes, it comes down to how we take in what the world has to offer, and how we proces it. Once people can understand that, then they can look at our work, and understand more about us and what we're trying to do. That's why over the last ten years we've tried to maintain our independence, produce our own records - even Jon putting out his records with Soul Note. He's still producing them himself. If you look at the credits he's the producer. It's still an issue of how the work is rendered and brought to the public. There's a care that we put into that which reflects a desire for people to relate to what we're trying to do and the culture that we come from. That's why Asian Improv goes on, why we put out the newsletter, why we put out our own publication. We want to express ourselves. It's not about relying on some magazine to deal with it, but having a vehicle for the expression of the thoughts and ideas of those in our circle among who we are working. A repository of works by Asian American musicians In Motion Magazine: Where is Asian Improv going and how does it fit into the modern era of music? In Motion Magazine: Where is Asian Improv going and how does it fit into the modern era of music?

Francis Wong: Asian Improv is a repository of works by Asian American musicians. People are going to put work there, and it's almost for safe keeping. You can go to Ken's house and you can see all the stuff that ever came out that we've been in contact with. Even people who want to get Jon's Soul Note recordings come to us. We make sure we've got it. Asian Improv is going to continue to be the repository and archive for the representations and the works of Asian American musicians and the people that they work with. I think it's only going to broaden. There's already a second generation of musicians doing work. We're going to continue to get international recognition. For myself, I'd like Asian Improv to be a part of an institute, or a college, where we'll have a way to be that repository of the work and be a vehicle for the passing along of the legacy. We've put out recordings and done the newsletters. There's that level of documentation. With this journal we want to start a more in-depth documentation of the process. It's going to include people like George Yoshida who's documented the history of Japanese American music of previous generations. It includes Ken Yamada, Eric Chow, and Yvonne Liu trying to chase down Asian American record companies that existed in the '50s who documented the work of Asian performers. Artists teaching. Creativity and analysisIn Motion Magazine: What are some of the main concepts you bring out as teachers? Jon Jang: Since I started at the UC Berkeley Jazz Ensemble as an artist-in-residence, my general impression is that a number of students don't know about the broad history of the music and that that history is the value and power of the music. Part of my role as an educator is to help develop students so that they can make mature decisions and begin to look at music and life in a meaningful way. I don't want to impose that on them, I guess it s a nurturing process. But in interacting with students as an educator you want to encourage a collaborative partnership. One of the primary roles as an educator is to recognize failure as an aspect of discovery. I find a lot of students are learning skills and methodology. What's more important though is the process of how they get there. There's creativity and then there's creativity in the real world. A lot of students have a lot of enthusiasm, a lot of ideas they can initiate, but putting it into reality is another thing. It's a combination to me of right-brain thinking and left-brain thinking. In academia there's too much left-brain thinking. What's powerful about the artists' role is we do both right-brain thinking and left brain thinking. We're dealing with creativity and also analysis. As Francis was saying we're not only artists in concerts we're artists in interacting with people. The power of art is the aspiration towards the highest level of human expression. Francis Wong: To me it's important for young people to look for meaning, and to aspire to a mission in life. It's so difficult in the face of economic realities and the socialization training that people have to break out of just going along with the program. I feel people need to find a mission in life, to look at what is being done and look at what should they be doing. In terms of young Asian Americans, more people should go and be artists. There's just not enough people trying to do that. Not necessarily as professionals, although that is going to be part of it, but from the point of view of that being a human activity. People need to be engaged in a deep commitment to that kind of activity because that's going to be one of the things that is going to save the world. You have to learn how to surviveJon Jang: There are young students who have a lot of opportunities and they could develop the skill to become an artist and become successful, but it could be in a non-humanistic and an opportunistic way. Francis and I feel that we were fortunate to have had experience with a number of people during the counterhegemonic period that were seeking an alternative vision. We were encouraged to redefine what the United States is about. The one thing we have to do with young students who want to follow a path similar to Francis and myself is not only encourage them but also let them know there's obstacles and you have to learn how to survive. Francis Wong: For example, at UC Santa Cruz people have to fight to be themselves and to define themselves, especially Asian Americans, and I'm sure a lot of the other students of color. I get in dialogues in class. Some young people say to me, 'Well you guys defined who you are. You created the Asian movement. You created an Asian American identity. We come along and we take these classes, we get Asian American identity but so what are we supposed to do now? What is the next step?' And that's really the question. Yes, folks come through Asian studies, they can read it in a book. There's so many Asian students they can feel that they are Asian. There's no denying it. But it's like 'what else is new?' What am I supposed to do? What's that next level? Relating this to our earlier discussion about the diaspora, I feel that as Asian Americans we need to provide leadership in society overall. In our period we were looking at getting our consciousness together, but now we have to offer leadership in the world. We have to strive for that. That would be a good thing. You know, we thought it was a partial victory that we got to give this concert at Herbst Theater which we sold out. But you know what one of my students said? "You mean they made all the Asians play on one night?" It's interesting that perspective. They believe from their perspective that we should have been featured throughout the whole festival. As far as they're concerned what we are doing is very important. I like that vision, and I encourage the students to proceed on that level of thinking. In our day, it was 'please recognize me, please give me a gig, please whatever' and you had to fight for those things. The meaningful legacy of the work that we've done is for people to take on trying to save the world. |

Part 1 - Founding An Independent Recording Label Published in In Motion Magazine February 25, 1998. |

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2020 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

This is part four of an in-depth conversation with composers / musicians Jon Jang and Francis Wong. It marks the 10th anniversary of the founding of the independent recording label Asian Improv. At the time of this interview, Asian Improv had issued over thirty recordings by such artists as Francis Wong, Jon Jang, Glenn Horiuchi, Miya Masaoka, Jeff Song, Mark Izu, Genny Lim, and many others. The interview is in five parts and covers a wide scope of topics ranging from the reasons why these composers started their own recording label; how that label has grown; how Asian Improv related to the Asian American Consciousness Movement; multiculturalism; politics, music and spirituality; music and everyday life; and the composers' tracing of their musical histories and compositions. Interview and photos by In Motion Magazine publisher Nic Paget-Clarke.

This is part four of an in-depth conversation with composers / musicians Jon Jang and Francis Wong. It marks the 10th anniversary of the founding of the independent recording label Asian Improv. At the time of this interview, Asian Improv had issued over thirty recordings by such artists as Francis Wong, Jon Jang, Glenn Horiuchi, Miya Masaoka, Jeff Song, Mark Izu, Genny Lim, and many others. The interview is in five parts and covers a wide scope of topics ranging from the reasons why these composers started their own recording label; how that label has grown; how Asian Improv related to the Asian American Consciousness Movement; multiculturalism; politics, music and spirituality; music and everyday life; and the composers' tracing of their musical histories and compositions. Interview and photos by In Motion Magazine publisher Nic Paget-Clarke.