|

Interview with Richard Haigh

of The Valley Trust Sustainable Development -- "Participatory Development” KwaDedangendlale, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

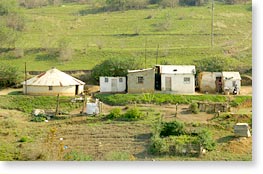

The Valley Trust is an NGO (non-governmental organization) located in KwaDedangendlale, the Valley of a Thousand Hills, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Founded in 1953 by a medical practitioner, Dr. Halley Stott, "the Valley Trust has since its inception taken a holistic approach to health, recognizing that good health is the outcome of development processes." The Valley Trust has several departments including Community Health Support, HIV/AIDS, Integrated Technology, and Whole School Development. The following interview with Richard Haigh, manager of the Integrated Technology Department, was conducted August 27, 2002 at the Valley Trust (“the room that we sit in was actually the original clinic”) by Nic Paget-Clarke for In Motion Magazine.

In Motion Magazine: Can you give a brief history of what happened over the years, how the Valley Trust developed into such a huge organization? Richard Haigh: You were probably a bit intimidated when you drove in with all the infrastructure but, as you say, there is a history. We’re 49 years old, our 50th anniversary is next year. In that time, we’ve grown from a very small organization of seven or eight people up to over a hundred, down to 45, and then have started growing again. Currently, our staff number sits at around the mid-’80s.Nutrition, promotive and preventive health

The idea was that people who came to the clinic would also receive training in how to prepare food, how to grow food and then they would often be followed up in their homes and supported at a household level to try and promote good nutrition and well-being. Over the years, and also given apartheid and the broader history of South Africa, there was a time when we were heavily involved in service delivery. It was service delivery that government wasn’t doing in former homelands -- areas reserved for black people -- building classrooms, labor-intensive programs, roads. Anything that was in opposition to government was funded. NGOs were seen as a channel to support other structures within civil society and we weren’t an exception. In 1994, with the first democratic government, obviously we reflected on what is our new role. As with many NGOs, this was also linked to funding cuts. Many donors preferred to fund directly the new government, the first democratic government. Many NGOs had to downsize and we were one of those. Our staff dropped to mid-40s and with that there was a panic. What really do we do? As an NGO we realized that our role had to change and what we had been doing maybe was no longer our responsibility. What was our responsibility?What happened is that we started to hand over a lot of projects that we had worked with to people. That was very problematic in the work in adult education, the work with pre-schools, the work with community gardens. We tried to hand over projects to existing community structures with quite mixed success. In Motion Magazine: How many people do you work with in the villages? In what ways? Richard Haigh: In terms of the number, it’s very hard to say because traditionally the Valley Trust worked in five tribal areas which are around here: (Emolweni, Kwanyuswa, Kwangcolosi, Emaqadini, Embo). Also, we decided that it would be in our interest to try and spread our work and our learnings to other areas within the province. At the moment, we work almost across the province but not in every aspect of the work that we do. We have several different departments at Valley Trust that all have a different focus trying to link to the four transformations statement (The Valley Trust Transformation Statement -- We want to positively change people's views of their own self-worth -- We want to increase people's awareness of the opportunity base for improved quality of life -- We want to optimise intersectoral collaboration -- We want to strenghten the positive perception of The Valley Trust based on quality, people-centered development work and good relationship) so the work varies. Apart from the staff, we employ eight hundred community health workers throughout the province and we manage that within the KwaZulu-Natal district health system.But we are not only working at grassroots. We have some affiliations with tertiary institutions and other organizations so our work is at different levels. We are also trying to work with policy, although that is very difficult given that we are far from the capital province Gauteng, Pretoria where most of the policy is made. In that way we could say our distance, six hundred kilometers, marginalizes us. Community-based Health Support and HIV/AIDS

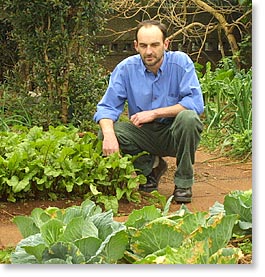

Richard Haigh: It is at the moment. With our Community-based Health Support department we are working with the district health system across the province with the Onompilo who are community health workers. Within this department we are obviously working in HIV/AIDS, although that is a cross-cutting issue. HIV/AIDS is a cross-cutting issue was decided at a strategic level within the organization given its impact. AIDS is not an abstract concept it is a reality if you are a field worker. We are working with not only the health worker program but also with rehabilitation, voluntary counseling and testing, and home-based care. We are working with youth and Dramade.Richard Haigh: But we also have other departments. Whole School Development is one. There we are working with school governance. We work with school infrastructure, as well as science and mathematics. We have a very, very exciting bit of work, which is very much a pilot, in personal development. Trying to change the relationship between the educator and the learner. Using language and making people aware of language, particularly educators, in the classroom context. Seeing how the relationship between the learner and the educator shifts. That’s been very interesting because one of the spin-offs from that is that although traditionally the education system has been very authoritarian, when you change that dynamic the teacher becomes not only a teacher but also a social worker. They see not only Nic as a journalist but the whole idea of Nic and what his world is. That is very, very exciting. For example, we are involved with what you could term slow-learners. But you can be smart in many different ways. It’s not just mathematical smartness that can be recognized in the schooling system. The Integrated Technology Department which is trying to use land and links with this department and indigenous knowledge to build the confidence of children who wouldn’t perform within the class context but may develop confidence and self-worth out of the classroom. We support them in that area. Participating technology development Another department is Integrated Technology. What we are working with there is people and appropriate technologies trying to develop technologies with people. This department includes as well the Social Plant Use program which explores the relationship between people and plants. We are working with farmers in organic and sustainable land-use practice as well as with traditional health-use practitioners. In Motion Magazine: Integrated Technology is the department you manage. Can you speak more about that? Richard Haigh: As I said, there are basically two units. One is the Appropriate Technology unit and the other the Social Plant Use. The Appropriate Technology unit is working in sanitation, water, earth technology and building, and some labor-intensive approaches. We are very much trying to shift our work to be along the lines of participatory technological development instead of transferring technology onto people. The rest of Africa has passed that. They are developing technology with people but unfortunately in South Africa we often find technologies for people and try to get people to adopt them and from that we make money -- not us, but industry. We have been looking at trying to develop technology with people, to consult people in a meaningful way in exploring what technological options are there. What they can use that they can then innovate and adapt and improve, rather than just be the recipient of technology which comes from big industry or from the North. Technologies, too, that don’t undermine the indigenous knowledge and technical knowledge that we have in communities. Technologies that don’t destroy the social fabric and relationships of communities. In Motion Magazine: Can you give an example? Richard Haigh: People have forgotten how valuable their that indigenous technical knowledge is to themselves. They are so used to it being undermined and not valued and being scorned that they overlook its real meaning, its broader meaning within their community. To give you an example of actual technology, there is compressed-earth technology which is a very interesting technology. You can buy a machine from France or Germany that you import for quite a sum of money and you add, depending on your soil type, two percent cement. You don’t need to bake the bricks. They are sun dried, cured, and you often don’t need to transport them because you can make them from, given the hills that we have here, from the platform you cut. You can make the blocks on site. In ’97, we had huge floods and many people’s houses collapsed, but not everyone’s house collapsed. And there were good reasons for that. Between the way you build your house and I build my house there are small things but meaningful things that make the difference. It’s those types of things that as a department in the past we’ve really overlooked and we need to focus on. What are those small things? There are certain skills where we wouldn’t have to import a machine from faraway but use traditional methods of building.

Richard Haigh: The Social Plant Use program explores relationships between people and plants. In the past, at the Trust, we worked with vegetables but if you look at the relationship between people and plants, it’s far more than vegetables. It’s more than the physical. It’s more than just nutrition. It’s also about the social, the mental, the cultural value of plants. In Motion Magazine: What does that mean? Richard Haigh: If you look at certain customs, certain ceremonies that are held … . For example, Impepho is used – it’s a type of incense, it belongs to the Helichrysum spp and it is used to communicate with ancestors. What is happening to plant stocks of that? When you start to lose the plant you start to lose the custom and with that part of the culture, part of the roots that make us who we are, what we are. Another plant, nthlancos, the Ziziphus Mucronata, if someone dies in a car accident, in a prison or in a hospital, part of that plant, a branch of that, is taken to collect the spirit of the person. Although the body is removed, obviously, you still need to capture the energy of that person and a branch of the plant is used to capture that energy.When you start to lose that plant … . If you look at the threat of many of the indigenous plants … . If you go to Durban and walk through Warwick Triangle where many of the medicinal plants are sold you will see there are thousands … . There are over six million rand a year traded on the street in Durban alone. Most of those plants come from wild areas. They are not cultivated plants and once we start to lose them we start to lose part of our culture, part of our heritage and association with the ecological world. Regenerate plants species that have a cultural value In Motion Magazine: Is that happening? Richard Haigh: If you look at the amount of the plants which are being harvested it’s clear that we can’t maintain that sort of harvesting rate without regenerating them. In Social Plant Use we are trying to regenerate plant species that have a cultural value. In Motion Magazine: Why is so much more being harvested now than before that it is causing them to disappear? Richard Haigh: The plants have always been used, you are right about that. I think with the shift of many people to urban areas it’s created more demand and also people recognize that income can be made from harvesting and trading in these plants. People will go and of a fifty- or sixty-year-old tree remove most of the bark from that. And while they are not using it, they themselves are not diviners, they are generating income from harvesting that bark.

Richard Haigh: What we are learning is people have an interest in cultivating -- the traditional health practioners and the farmers, for example -- in cultivating plant species. People are very interested in keeping their culture alive and recognizing the value that children … . Children are no longer that interested in eating traditional foods. Many people say, “You know, my children in the house they don’t want to some traditional foods. If you eat them they think that, you know, I am primitive and uneducated.” We are recognizing that through these plants we pass on culture. We pass on rituals. We pass on stories. That’s significant. In terms of the cultivation of these plants, I could say that we are affirming knowledge where in the past it has been undermined by education systems and general development, ideas of development paradigms about whose knowledge system is valued, Western models of development. People are recognizing that, yes, we can celebrate preparing traditional foods, growing traditional crops, as well as other crops. People conserve what they value. Once people don’t value those particular seeds or that particular crop, you lose it. And once it’s lost -- we can do many things but we can’t bring it back. Those plants that we’ve had, those food crops that you see in the poster, have co-evolved with people. They are what they are today because of the relationship that there has been with people and the environment. In Motion Magazine: And how does that connect to health? Richard Haigh: In the way that many traditional foods are prepared. Not only are they better adapted to the environment, but some of the centers of primary diversity of the traditional foods that we still find are here, apart from things like maize and pumpkin that came from the Americas, Central America. It links to health in terms of the way the food is prepared and the absorption of nutrients by the body. It is not as refined. And also in the treatment of HIV/AIDS and some of the associated opportunistic infections -- boosting the immune system for example. There’s the story about the African potato whose benefits were identified through the practices of traditional health practioners then copied by pharmaceutical companies and produced synthetically. They identified the active ingredients, but that knowledge they got came from traditional medicine -- the knowledge to treat opportunistic infections, for example oral thrush, sores and itchiness. In Motion Magazine: So bio-piracy is occurring in this area? Richard Haigh: That’s a KwaZulu-Natal example of where plants were used traditionally to boost the immune system and through prospecting and the research of tertiary institutions plants have been identified. There’s a huge interest in the work with traditional health practioners and we’ve had to be quite careful as an NGO at what level we engage and what we document. Declaration of the Valley of A Thousand Hills

Richard Haigh: The Valley Trust has had an association with GAIA Foundation for a number of years and we agreed to host an exploration of community rights. In that agreement it was agreed that some countries would do mini-studies at a very informal level on community rights. We looked specifically at issues of seed and what were some of the feelings at the community level which we had documented. It was a platform where people from different countries could meet and share issues and experiences. The Declaration is about redressing power-balancing, keeping options open for people who the Western world may call “less developed”. In Motion Magazine: Different African countries? Richard Haigh: Different African countries. Although there were a few other people who presented on indigenous people’s rights. In Motion Magazine: What do you think of that Declaration? Richard Haigh: Being part of the Declaration, I think it’s great. But it’s one thing having a declaration which we think is very precious and meaningful to us but how do we use that to actually change and influence? Just on the genetic engineering, that’s very difficult because there are a lot of people who are promoting the biotechnology and specifically genetic engineering. You can have whatever declaration you like, but what is the weight, what is the force behind it, can it help you get a policy shift? Other than to share it and use it as a document to create awareness? I think part of the value is not so much the Declaration as the processes and reflection in trying to articulate what’s in it for the people who were there and the experiences and learnings. So, yes, the paper is a tangible product of process but maybe the real value is trying to articulate and clarify what really are the issues. It’s in that process where the real meaning sits. But, certainly, we have used the piece of paper with government. But the government hasn’t been very sympathetic to it. On genetic engineering the South African government is arrogant, caught up in the technology race, too insecure to set a more meaningful trend, to be influenced by multinationals and their ideas of what they see are the needs of people.

Richard Haigh: Let me start to answer that by focusing on children’s health. Xoli Ngcobo and I did a community situation analysis looking specifically at early childhood development. From that, looking at healthcare and provision for children we would say that children still are extremely, despite six years of a primary healthcare approach, children are still extremely vulnerable. HIV, rape, sexual abuse, TB, and immunization are issues in rural community that children are effected by and even die from. Also, alcohol, increasingly drugs, and home-made brews. In Motion Magazine: Can you put that quantitatively? Richard Haigh: If we look in terms of the health of one of the schools that we were at speaking to children, enquiring about children who are challenged within the school context -- how did people record disability? How did people work with that? At one of the schools, the teacher said. "You know, the incidence is probably three times higher but we don’t have the understanding to pick up disability within the class situation. We don’t have the training." The school had about 30 children that they had identified but they said if we actually tested children for hearing and sight, just those two things, it would make a big difference. With malnutrition, while things like kwashioko and merasmus aren’t that high, relating to chronic malnutrition, child wasting is still extremely high -- the number of children who go hungry, who don’t get a meal in a day. Vulnerability and food security The impact of retrenchments, of people who have lost jobs and no longer bring an income home because they have been retrenched from urban areas, like working on mines, was very, very high. That really effected communities in terms of their vulnerability and food security. For example, people say, "Yes, we know that there are orphans in our community and in the past we all chipped in, but the difficulty now is that people in our own house are starving. Now, to give support to other households and orphans, we just can’t do that. If we ask, “In the past, what was your harvest like?” People say, “Our granaries were full. Inqolobane (traditional granaries) were really, really full. We had plenty of food.” “Well, what’s changed?” “Our soils are tired. “What do you mean the soils are tired?” “We don’t have money for fertilizer. If you look at the prices of the fertilizer and lime recommendations we just don’t have the means to apply these things and don’t get the yields we’d get.” As well as people don’t plow any more with oxen as much as they used to. People prefer the tractor and its status. The relationship to the land has changed. But, back to your original question, in terms of the health situation, certainly the number of people who are infected with either TB or HIV positive or they have AIDS, that number has definitely, definitely increased and we see that from working with people at household level going and visiting families. In Motion Magazine: What has it increased to? Richard Haigh: I think the prevalence rate is nearly 40% of the people, which is quite high. The social fabric and traditional support In Motion Magazine: The standard of living -- how would you describe it? Richard Haigh: Many people rely on a pension or some sort of government remittance, be it the orphan grant, or pension, or disability grant, or single parent. Disposable income has gone down with inflation and the increases in maize prices, staple foods. Also with the impact of HIV and AIDS the asset base of families has decreased for many households, in terms of their livestock, their vulnerability, their ability to withstand stresses and shocks. People aren’t as resilient as they were before and there are many reasons for that. Also, the challenges to the social fabric and traditional support systems within communities are very threatened. For example, with HIV/AIDS the concept of witchcraft. Many people will not say, “Well, they died of AIDS.” They will say, “They were bewitched.” Bewitchment is a complicated belief system. The levels of suspicion have increased between households which formerly supported each other. I don’t know what it’s like in your neighborhood but I know that on the street I live in, if I want a plumber I would never think to walk down the street to ask if there is a plumber. You know, I look in the yellow pages. But in rural areas because people have less options, there is more of a support strategy between households and that is being stressed as people are pressurized ruralness. In the past widows were supported. You find now widows are losing their livestock. In places the traditional support system has eroded. People are more opportunistic. They cannot let people know they are vulnerable. Losing chickens, losing goats. There have been many incidences like that. That never happened in the past. While it’s true that some households may have more technology, maybe a second radio, cellphone, some even a television, they may even have more opportunity or access to the city -- but in terms of their real social fabric and standard of living, I think that it has declined. There are very, very few households where both women and men work. That is uncommon. It’s usually one or the other.

Richard Haigh: We still are in service, and we’d be kidding ourselves if we said we are not, but we are in a different type of service. Our service is more linked to people-centered development and facilitation whereas in the past it was more delivery of products, of goods. In terms of the processes, if I look at the Social Plant Use program, for example, in the past, as an organization, there was a time when we worked with nearly 83 community gardens across four tribal areas. Although you could say we have been quite successful in that, we realized that if you added up the whole area of land that the community gardens occupied and you added up the total amount of land around the homestead, and the area that was being used for food production around the homestead -- the area around the homestead was far, far, far greater than that in the community garden. And we couldn’t teach people anything else in the community garden. So, shifting to the homestead meant that we could work in a more integrated way and also that we could engage other members of the family and also promote indigenous knowledge and skills. We could get closer to the reality of people’s everyday life. This has also helped to shape us as development practitioners. We could work not only with women but where possible with children. We could work with fruits which we couldn’t do in community gardens. We could work with medicinal plants, veterinary plants, other plants which had magical properties or other healing properties. We could work with fodder plants. All within a household context. In addition to that, people who were working in their home gardens could also look after children or other members of the family or household who were sick or needed more attention rather than walking a kilometer or half a kilometer to a community garden. Also, the way that we have worked at a household level in food security issues and land use has linked to interest groups. Groups where people have a common interest or something that they would like to explore, for example, to sell their produce or improve marketing options. It’s quite a process of letting them evolve. Our role as facilitators has been at times producing new possible technologies, sometimes germ plasm which has disappeared that people would have an interest in, or some other traditional foods. We try to facilitate the exchange of experiences of learning and problem-solving. That type of approach is an example which is quite different to the way the Trust has worked in the past where we worked more with committees and structures. We sort of turned that on its head. In Motion Magazine: Did a change in approach happen in all the departments at the same time? Richard Haigh: No. The change for us came about because we realized that there was a lot more meaning in working the other way. In Motion Magazine: When was that?

In Motion Magazine: After the elections? Richard Haigh: Just after. In Motion Magazine: So that was the reassessing of your role that you spoke of earlier. Richard Haigh: As an NGO we needed to find what was our new role. Given that we were trying to hand over many structures that we had worked with, as reflection on that, and also re-assessing what our work had been in the past, and what it could be, we realized that there were other options. Also the awareness around HIV and AIDS wasn’t so obvious then but that has also been a catalyst for shifting the way that we work. As I was saying earlier, there are many examples, now you can visit households where people are dying and have died and people talk about losing, caring, nursing people. In Motion Magazine: Do you feel this is a good way to approach building a democratic society? Richard Haigh: I think one thing that is quite clear is that you need to build on the resources that people have and the social networks that exist in community. I think they have in the past often been overlooked. Trying to work with existing assets in a community is a good base on which to build a democracy at a very, very local level -- you are trying to build the social fabric within a community. It’s not just about infrastructure. It’s primarily about people. That’s really quite a shift. In Motion Magazine: What does democracy mean to you? Richard Haigh: It’s an opportunity, and a reality, where people can voice and try to materialize their dreams, the systems of governance that are meaningful to them, that have meaning in their daily lives. Rather than being something very abstract coming from over there, democracy is where people can influence decision-making and minority groups can be not only tolerated but recognized for their contribution, for the diversity in what they contribute to society. In Motion Magazine: You speak of existing assets and you described the people-centered approach used in the Social Plant Use program, does that approach apply to healthcare? Richard Haigh: Yes. I hesitate for a minute because as you can imagine when you have a large staff to try and coordinate it and be more process-oriented it is actually a lot harder. You sometimes become a victim of your numbers. But certainly the idea of working with assets that people have -- and that includes knowledge and local resources -- is there. Working with that paradigm of what people have in a community, as a starting point, is there. The principle is there. In Motion Magazine: What does that mean -- that paradigm? Richard Haigh: It is what people do have. To start, it’s whether you have a needs-based approach or an assets-based approach. If you start with a needs-based approach, yes, it’s true you can satisfy people’s needs. We need. Well, I need lots of things. Maybe I need an aeroplane, and new CDs, and I need a holiday at least once a month. But the reality is, well -- What do I have? But if you are working with the assets-based approach you are saying, "OK, you may need those things, but let’s look at the glass. “Is it half full or half empty?” We are really saying, “What do you have? What resources do you, Nic, have?” Not, “What do you need.” With the assets-based approach, when you can get people to realize what assets they have, and what resources they have -- and everyone has some resources -- it gives you the sense of empowerment. That I can do something. I have got something. And sure I may be missing many things, but it’s affirming.

Richard Haigh: It sounds so idealistic. OK, you would come with the assets-based approach, and the person might come to you and say, “Listen, I need food. We are starving.” Can we use that as an example? In Motion Magazine: Alright. Richard Haigh: So you say, “How many of you in the household? How many of you in the family? Is anyone working? No. Yes. Who? Where are you getting income from?” And now it becomes a bit more complicated. We have had this exact difficulty, so that’s why I raise it. We’ll say, “Where do you live? Can we come out and have a look?” And say, “OK, you’ve got, maybe, some animals. You’ve got land. Is the land being used? Have you got water? Where are you getting water from? What tools do you have?” We try to get some sort of immediate relief for that family if there really is a crisis. But also we try to encourage them to work and mobilize those resources that they have to grow something with what they have. And, by the way, using organic gardening. We have only been organic. It’s working. We have only been organic in our approach. In Motion Magazine: Is it important that you have multiple programs? Richard Haigh: They help each other out but also what we are not doing is one-off training. That doesn’t really go anywhere. In Motion Magazine: What does that mean? Richard Haigh: To train people for four days or a week. You all get very excited and you go away and what really do you do. In terms of being people-centered in our paradigm, we are trying to work in a phased way for a length of time using the action-learning cycle where you negotiate the objectives. You negotiate how you could see changes in what you are doing and you agree on that. The action-learning cycle starts with the learning, then action followed by reflection, and lastly learnings. This would then lead to improved planning in the next loop of the cycle that incorporates learnings from the former cycle. How will we know then if we are meeting our objectives as a group? We facilitate that process. We negotiate that process. We say, OK, from that three-day training what are the actions that would happen? In that three days we would start, for example, with soil fertility as a base. What are ways of keeping soil? Traditionally what did people do? What resources do you have? What other things do you know? Who’s experimented? Who thinks they are good at managing their soil? What causes soil fatigue? How does it happen? What are the components of that?

OK, what have you seen? The group evaluates what other people have done. Then we would take the next step. We could do that type of facilitation work for up to two years. Using each time they meet as an option to reflect on implementation then re-plan. You can’t short-cut development In Motion Magazine: This is an approach to sustainable development? Richard Haigh: Yes. You need to work where people are at, in their context. In their reality. Work with them. And to do that meaningfully takes time. You can’t short cut development. You can’t short-cut learnings because in order to learn you have to do and reflect. You have to implement. In Motion Magazine: How do you think this differs from, say, Monsanto’s approach? Richard Haigh: In terms of Monsanto, they are undermining whole communities that have taken hundreds of years to get to where they are at. Monsanto’s primary concern is profit --not people. And while I think the difficulty is that because of past systems we haven’t really acknowledged what’s there and documented what is there, already that is so threatened by, for example, genetic engineering. We just don’t know what implications that could have. And it’s not only implications on the seed supply and patenting of life forms, it’s also a contributor to the breakdown of societies and systems within communities which are already quite vulnerable and quite stressed due to economic situations and AIDS.Many people in South Africa, a lot of municipalities, a lot of government, they are all talking about poverty alleviation and local economic development. And the ideas in people’s heads of development are very, no offense meant, very American ideas of development. It’s quite tragic. And it’s not sustainable. It’s not. But, also, sometimes you need to go through it to come to that conclusion or to learn that. To a degree. How do you shortcut that realization given the history and complexities of what’s happened in this country for example?

Richard Haigh: The Declaration helps with that but it also helps in terms of solidarity, in terms of what you are doing is meaningful and does have value. For that it can be hugely motivating to participate in activities that manage to draw up and narrate those sort of conflicts, those issues, those feelings, that common cause which is uniting and strengthening quite deep down. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Published in In Motion Magazine, June 8, 2003 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2018 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||