|

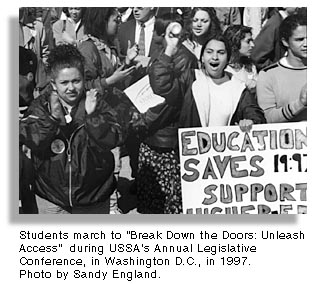

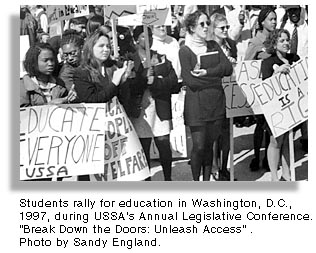

United States Student Association A National Movement for Affirmative Action "Rethinking the Way We Organize" Jennifer Lin Washington, D.C.

Jennifer Lin is the director of the Student of Color Strategy and Policy department of the United States Students Association (USSA). The USSA represents millions of students across the nation. Students can join USSA three ways: 1) when their student body votes in a campus-wide referendum, 2) when the student government votes to join as an individual campus, or 3) campuses join through, or as part of, a state or system students association. The primary focus of USSA is to organize around grassroots legislative issues as they pertain to expanding educational access. USSA's history has been closely linked to organizing by students of color. The interview was conducted for In Motion Magazine by Nic Paget-Clarke (from San Diego by phone), August 31, 1998. Affirmative Action Around the U.S. In Motion Magazine: What is the national situation of affirmative action? Jennifer Lin: Nationally, students are faced with a lot of attacks on affirmative action. They are responding by organizing their communities, changing public sentiment, and taking a stand. Students are addressing all the myths and misconceptions about affirmative action and saying that this is something we want to preserve. There's different ways affirmative action is being challenged. One is through law suits directed at the school or state system. Another is through state legislation. In the past year bills have been introduced in places like New York, Georgia, and Colorado. Another anti-affirmative action approach is through review and elimination of policies in public schools such as in North Carolina. And of course, Washington State is facing Initiative 200. Very similar to California's Prop. 209, this initiative would eliminate affirmative action policies. In the North Carolina instance I just mentioned, the university president Molly Broad has called for a system-wide review of affirmative action policies with the intent of eliminating them. Students there have been organizing in coalition to change public sentiment. They've been holding rallies, writing editorials and encouraging the university system to take into consideration student concerns as they review their affirmative action policies. Students welcomed the review of these policies but with the understanding that affirmative action has benefited students as a whole and that those programs and policies should not be completely eliminated. At the University of Colorado at Boulder, at the end of school year in June 1998, the governing board of the Colorado university system basically eliminated a lot of the standards for affirmative action. This action replaced concrete goals of enrollment for minority students with more vague terms. Instead of saying we are going to admit 18.6% of minorities into our state public institutions (18.6% was the number of minority students graduating from high school), instead of having some concrete goals to work towards, those numbers were eliminated and the situation become vague in terms of diversifying and increasing access to education. Without defined goals, how do you know when you've adequately diversified? In that case a lot of students brought their own proposals to the table as to what they would like to see in an effective affirmative action policy, what they would like to see as effective recruitment and retention policies. In Michigan, a law suit is pending against the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. There, students have been organizing to try to change public sentiment about affirmative action, to uncover the motives of organizations like the Center for Individual Rights (CIR). The CIR is funding this law suit based on opposing affirmative action. They've funded a number of other law suits including the Hopwood Case in Texas. In Georgia, another lawsuit is challenging the admissions policies of both traditionally white as well as historically black colleges and universities. In New York, attacks on open admissions and remedial education are linked to affirmative action in the sense that a large portion of New York's low income, minority, and immigrant students are being shut out of the CUNY system.

Jennifer Lin: The last bill that came out against affirmative action was part of the re-authorization of the Higher Education Act. The Riggs amendment sought to end affirmative action in higher education. That failed in Congress very much due to the efforts of students who wrote their senators and representatives saying that they did not support the Riggs amendment. Stopping the amendment was a real success in terms of students organizing and lobbying successfully for affirmative action. The Significance of the Houston vote In Motion Magazine: People voted in Houston to keep affirmative action. What was learned from that vote? Jennifer Lin: It all goes back to language. How are initiatives and legislation written. Language is also coming out in the case of the initiative in Washington. People see the language that was used in California for Prop 209. Terms such as "non-discrimination" and "policies that are not based on race" conjured up images of the civil rights struggles for equality. But when people see that this language is being used to get rid of affirmative action programs, most people would vote against such propositions. In Houston there was a real effort to change the language so it was clear it was going to end affirmative action policies. That was one reason why I think a lot of people voted to keep affirmative action. Since the vote, however, there have been developments in Houston. According to information from the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center listserve a state district judge in Texas ruled in July that Houston's language on its November 4th ballot, language which specifically mentioned the end of affirmative action, did not reflect the intent of petition signers who put the initiative to a vote. The initiative, proposition A, included a clause about the "end of affirmative action for women and minorities" in employment and contracting, instead of the "shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity" that was used to sway voters in California under Prop 209. With the new language, voters defeated Proposition A in 1997 by 54% to 46%. They voted to keep affirmative action. Petition organizers, however, filed a law suit claiming that the initiative's language as it was presented to voters did not reflect its original intent. This is a case where the language was direct. It didn't distort civil rights language, and voters chose to preserve affirmative action. But now a judge has ruled that that election is null and void, and money will have to be poured into holding a second election with different language than that used in Proposition A. At this point, we just hope that Houston will appeal the decision and that the original election will stand. Its interesting that the judge ruled that calling the initiative for what it was -- an end to affirmative action -- was deceptive. But is disguising the language as "non-discrimination" and against "preferential treatment" any less deceptive? But I think there's still something to take out of this decision -- that how the whole question of "non-discrimination" and affirmative action is framed really affects how voters will respond to a particular initiative. In Motion Magazine: Has understanding the significance of the language used in these initiatives had an impact on current campaigns? Jennifer Lin: I think a lot of students have been aware of this in terms of holding rallies, writing editorials and explaining the language of a piece of legislation, of an initiative, of reviews of affirmative action policies. Students are showing a lot of these attacks for what they are. They are uncovering that "non-discrimination" and "having policies not based on race" does not mean that you are going to have an equal playing field. Affirmative action is a proactive way to ensure that, in this case, education is open and accessible to all. I think a lot of students have been uncovering the distortionist civil rights rhetoric for what it really is. It is a distortion. An Environment Where People of Color Are Not Heard

Jennifer Lin: You'll find in a lot of places, for example California where Prop 209 passed, that there is an environment in which many students of color, people with disabilities, women, people who fall under affirmative action, -- do not feel comfortable on campus. They feel their presence is not important to campus administrators, to people who are making decisions to cut affirmative action. And this is going along with the scape-goating in immigration. It's creating an environment where people of color are being attacked, women are being attacked. Those who are seen to "benefit" from affirmative action are being attacked. Students don't feel that their being at a college or university is a priority to anybody. It goes back to looking at how the attacks on affirmative action have been followed by drops in financial aid, and other sorts of linked problems. For a lot of students of color it's linked to their cultural spaces and their student group getting less money. It's linked to an environment of a rise in hate crimes and hate violence on campuses. People may see a cut in funding in their Black Student Union, but you can also see this cut as linked to the attacks on affirmative action. These attacks create an environment where people of color are not heard. Their resources are not prioritized. Making an environment where people of color and women feel comfortable is not prioritized. It's leading to the high transfer rate and the low enrollment rate of people of color. Re-thinking the Way We Organize In Motion Magazine: How thorough is the response to defend affirmative action? Would you call it a movement? Jennifer Lin: I would definitely say that in the places where students have looked at the way they organize and have realized that they are able to defeat an anti-affirmative action bill and are able to preserve affirmative action and the coalitions they make -- those campaigns don't just die. It is a broader movement in that people are recognizing that the coalitions that they build, the strategies that they build, what they learn from these campaigns, will also inform the way they do future work, a future commitment to social justice issues. There is a body of students who are very committed to that. In places where students are fighting to defend affirmative action it's forced students to make very strong and sustainable coalitions. They are not just working within Asian American Student Unions, or Black Student Unions, or Latino/Chicano organizations. Students have learned to branch out and make strong sustainable coalitions with the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) community, with the women's resource centers. Students are branching out and making as large of a mass movement as possible. Anti-affirmative action has had detrimental effects but also it has forced us to rethink the way that we organize. In Motion Magazine: There's not a sense that this is a lost cause? There are some who say affirmative action is dead. What you are describing is a situation where students around the country are organizing to deal with the preservation of affirmative action. You feel that there is not a sense of defeatism? Jennifer Lin: Not at all. According to the Leadership Council on Civil Rights, twenty-three different amendments or bills were proposed in eleven different states last year, 1997, and none of them passed. This was in places like Florida and Ohio. None of them came to fruition. In those cases where there were anti-affirmative action bills introduced, students effectively organized to cap them. Affirmative action was kept so that these anti-affirmative action bills would not go any further than California. I would say that it is not a lost cause due to student organizing with coalition groups in the community. We've been successful in making sure that people see that a lot of benefits come out of having affirmative action. Affirmative action has opened doors for a lot of people and it continues to be necessary. In Motion Magazine: What do you think are the main battlegrounds? Jennifer Lin: I think the battlegrounds are in the realms of "public sentiment." Public sentiment effects how a person votes. It effects how elected officials vote when there's a piece of legislation in their state senate or state assembly that will impact affirmative action. There is the battle ground of addressing the types of distortions that have been coming out about affirmative action. For me, its facing up to family members and friends who still believe a lot of the misconceptions about affirmative action. Other battlegrounds include, particularly for students of affirmative action, the formation and preservation of ethnic studies, and the staffing of student recruitment and retention. It's important to look at the connections between affirmative action and the preservation of cultural and political spaces in dorms on campus, of women's resource centers and rape crisis centers. In Motion Magazine: What is the USSA doing to defend affirmative action? Jennifer Lin: One of USSA's foci this year is to have grassroots organizing trainings in six states: Colorado, North Carolina, Michigan, Washington , New York, and Georgia. The goal is to provide a consistent message to defend affirmative action, and to strategize nationally on how students organize around diversity issues. All the grassroots organizing weekend trainings will focus on affirmative action: how to build effective coalitions; how to effectively recruit people to your campaigns; how to win concrete goals, how to build an effective media campaign. These trainings and this project are being funded by Americans for a Fair Chance (AFC) based here in Washington D.C. AFC is a consortium of the nation's most prominent civil rights groups. And the organizing won't be, of course, limited to those six states -- USSA will be working with its member schools all over the country to educate congresspeople, local elected officials, campus administrators and decision makers on the need for affirmative action before direct attacks begin. It's an effort to move ourselves from a defensive position, to a pro-active position, staying one step ahead. In this way, when a system-wide review comes to a campus, or when an initiative or piece of state legislation gets introduced, those in office, those who are registered voters, those who are campus administrators will already have an understanding of the need to keep affirmative action policies in place. If there are students out there who want to get involved in USSA's action plans this year and in our affirmative action organizing project, they should contact our office at 202-347-8772. |

| Published in In Motion Magazine September 18, 1998. |

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2020 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

In Motion Magazine: Are there any bills in Congress?

In Motion Magazine: Are there any bills in Congress? In Motion Magazine: What are the impacts of these anti-affirmative action on the lives of students?

In Motion Magazine: What are the impacts of these anti-affirmative action on the lives of students?