|

Interview with Roberto Martinez (2001) San Diego, California

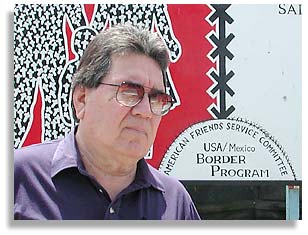

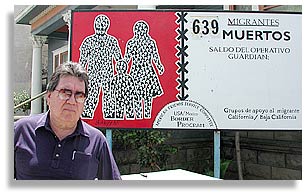

Roberto Martinez is a human rights activist and director of the U.S. / Mexico Border Program and Immigration Law Enforcement Monitoring Project of the American Friends Service Committee in San Diego, California. Interview conducted by Nic Paget-Clarke, July 7, 2001. In Motion Magazine: What impact has the Bush administration had on immigration policy? Roberto Martinez: One thing we have been able to see in terms of impact, concrete policies, is the extension and the support for things like Operation Gatekeeper. They have committed money, equipment, personnel, to not only Operation Gatekeeper but all the other operations on the border. There’s four all together. Operation Gatekeeper in California, Operation Safeguard in Arizona, Operation Hold The Line in El Paso, and Operation Rio Grande in south Texas. And the squeeze is on. There’s no sign of this administration or the INS, or anybody, pulling back in any shape, way, or form. The results have been deadly. You probably know about the 14 migrants who died in one group, in the Arizona desert, a couple of weeks ago. There were a total of 17 died on that weekend. There have been at least two to four dying every week in that border area. We consider these operations the main cause of the deaths on the border. Bush’s administration participated in high-level negotiations with Mexican officials, a couple of weeks ago, in San Antonio, to talk about solutions to the border deaths. I was very disappointed to see in the paper and to see on TV that what these two governments came up with was appalling. Their solution to the deaths on the border is to send more Border Patrol agents, to send three new helicopters, and to designate a small section of the Arizona border a high-risk area. In Motion Magazine: What’s a high-risk area? Roberto Martinez: It’s high risk because of the temperature and the terrain and the fact that the majority of the deaths are occurring there. This is a section of the border near Douglass, Arizona. However for us, the whole border is a high-risk area. Not even two weeks ago, a 19 year-old girl crossing with her family in Otay, a couple miles east of here, died from heat exhaustion in front of her father’s eyes and her brothers and sisters. They were abandoned by the smugglers. Why not designate Otay Mesa a high risk area? They are dying in the Las Cruces, New Mexico border area. The Laredo area. Why not designate those high-risk areas? The whole border is a high-risk area. In California alone, we have had 670 deaths since October ’94 when Operation Gatekeeper was launched. 670 men, women, and children in California alone. We are averaging each year from 145 to 150 deaths, in California. Prior to October 1994, we documented, at the most, 24 deaths a year. The Bush administration, like the Clinton administration, claims that it’s not the operations that are killing the migrants, it’s the coyotes, the smugglers, and the weather. Obviously, we know that, but the numbers speak for themselves. Prior to 1994, we documented 24 deaths. The direct cause of these actions, these deaths, is these operations. We have demanded over these last seven years that they abolish these operations, withdraw them, and evaluate the human cost compared to what they are trying to accomplish, which is basically nothing. They are ineffective. They haven’t resulted in the reduction of illegal immigration. It doesn’t address the root cause of immigration which is of course the economic situation in Mexico. What good are they? What is their purpose? What are the results? They are total failures. The only thing it has resulted in is one of the greatest human rights tragedies in the history of the United States. Another impact of the Bush administration comes not so much from what he has done, but from what he has not done, in terms of national immigration policy. For example, the IIRARA bill – the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act -- of 1996, which is causing the deportation of tens of thousands each year of legal permanent residents who committed crimes 15, 20 years ago. These people have paid their dues, but ever since 1996 the INS has gone into the records of anybody and everybody who has a legal permanent residency and committed any crimes and arrested them, re-arrested them, and put them in deportation with no judicial review, mandatory detention, meaning no bail, then directly into deportation without even being able to go before an INS judge. In other words, they are being tried twice for the same crime. This is ripping families apart across the country. Not just from Mexico or Central America or Latin America but people from all over the world. From Europe, Asia, the Middle East. Our detention centers are over-crowded with people being detained because of this unconstitutional, immoral law which even federal judges have declared unconstitutional. Two weeks ago, the Supreme Court ruled that the judicial review part of the law is unconstitutional and they overturned it, granting illegal residents judicial review. But the retroactivity is still there. Congressman Bob Filner introduced the bill, it’s called “Keeping families together”, to revoke this law. I went on a delegation with him to visit Camp Barrett, an INS detention facility out in east county. There, I ran into a gentleman in his sixties who worked with the Chicano Federation when I did, back in ’82. He’s a grandfather. He was arrested for a crime he committed over 30 years ago - a misdemeanor crime. When he went to court recently, under IIRARA, the government elevated that misdemeanor to an aggravated felony so that he could be deported. That’s what they do with this law. Now, he’s facing deportation. He had paid his dues. In fact, he didn’t even serve any time in jail as it was just a misdemeanor theft. He’s being taken away from his family - his wife, his children, his grandchildren. He has a home. He bought a home. This is the tragedy of this law. The immorality of this law. It’s punishing people twice for the same crime. In Motion Magazine: Do you think human rights violations on the border are related to NAFTA or globalization? Roberto Martinez: Absolutely. NAFTA has displaced tens of thousands of workers and farmers in Mexico by the flooding in of subsidized cheaper products from the U. S. In Motion Magazine: How? Roberto Martinez: The farmers down there can’t compete with a cheaper, subsidized corn for instance. I like the quote I read in Mexico where the farmers in Mexico said, “When the U.S. sends subsidized corn to Mexico, send it on trains with a lot of benches so they can take us back and get us jobs in the U. S.” The other thing is, when you have a country that exports 88% of its products to the United States and U.S. consumers are losing jobs at the rate they losing them right now it has to have a direct impact on Mexico’s economy. That old saying, “When the United States sneezes, Mexico catches a cold”, has a lot of truth to it. In Motion Magazine: Are there more migrants coming now than before? Roberto Martinez: Immigration is going to continue at the rate it is going now if not more, because of the recession that Mexico is going into right now as a result of our economic downturn. In Motion Magazine: Do you think it’s a coincidence that these various operations started around the same time as NAFTA?

In Motion Magazine: So the high death rate is partly because of the operations and partly because of globalization itself? Roberto Martinez: The ultimate solution is the economic development of Mexico but that is not going to happen right now. How can they create a higher standard of living and higher wages when their economy is in such a dramatic downturn? Rather, people are being forced to come north. A lot of them are coming into California. In agriculture, in the community, they are going to keep coming and no amount of enforcement at the border is going to change that. There are even boat people now in southern California. People are coming across in fishing boats. They are being found and caught in Mission Bay, La Jolla, Ocean Beach. Fortunately we haven’t had the tragedies there. But they are going to get across one way or the other. Fewer employer sanctions, recruitment in Mexico In Motion Magazine: What do the employers think about these operations? Roberto Martinez: The INS has pulled back on employer sanctions. What they are doing now is citing employers and warning them. I get calls from big restaurants saying, “I had to let my workers go because they don’t have papers. How can I get some workers who have papers to wash dishes and wait on tables?” I say, “I don’t know”. They are not being raided like they used to be. They are doing what they should have done in the first place, just verify the I-9 forms that they are supposed to do under employer sanctions from the 1986 law. The employers are responding, they are still hiring. But the reality, too, is a lot of major employers across the country actively recruit in Mexico. Like the poultry industry, which has been taken over by Mexican immigrants in the Carolinas. The meat-packing industries in the Midwest, in Nebraska. I’ve seen the ads. They prefer undocumented workers in these two major industries because they work harder for less pay and don’t complain. Just like the maquiladoras prefer women. Employers on either side of the border know how to exploit workers. They know who is going to work the hardest for the least pay. We are against guest worker programs because they have not resolved a lot of the issues with farm workers. They still live in inhumane conditions. No healthcare, no benefits, most of them live out in the open, in the brush, in the canyons and ravines in north County. As close as Del Mar. I’ve been down into ravines where all they have is a crate to sit on and a plastic sheet over the brush to keep the rain out. They live like animals and are treated like animals. We hope to bring some relief with our trailer project. In Motion Magazine: President Fox seems different from former President Salinas. Roberto Martinez: He’s more liberal in his way of thinking. He’s not very practical because he can’t influence U.S. policy, but at least he’s progressive enough to see that the only way people are going to stop dying at the border is to be able to work in the United States legally. The ones who are already here, they want a general amnesty. Fox also advocates allowing workers to cross the border legally, to be able to work. That’s what he’s trying to negotiate now. The U.S. government representatives, on the other hand, want to see a guest worker program. In Motion Magazine: The U.S. does? Roberto Martinez: Yes, and the Mexican government is supporting it. In that respect, we are very disappointed that they don’t understand what that means politically. Any more than did the delegation that was meeting to discuss the deaths on the border, when they agreed to sending more Border Patrol agents to prevent workers from crossing. All that’s doing is creating a Gatekeeper program on the Mexican side. If they block the way there in the Arizona desert, the people will find another way to cross. It will be either east of there or west of there, but they are going to keep coming. That is not a solution. There is only one solution. I’ve said this publicly and I’ve said this in letters - abolish these operations. Go back to the way things were. Let the people find their own way across the border. Because they closed off the traditional border crossings here in San Ysidro and Otay, people now have to circumvent two Border Patrol checkpoints and hundreds of agents. They are getting lost in the mountains. In the winter, people have been found wandering around for days at a time in the snow with no shoes. How can you justify people dying out there in such large groups? “We have to feed our families” People ask me, do you support open borders. I say, no. But for all intents and purposes they are open. People are going to keep coming. They’ve been coming for a hundred years. A ten foot-high fence isn’t going to stop them - two of them here haven’t stopped them. The weather hasn’t stopped them. 7,000 Border Patrol agents on the U.S. / Mexico border has not stopped them. What makes them think that more operations are going to stop them? It didn’t stop the Vietnamese from leaving Vietnam when they were drowning by the hundreds in the sea and being robbed. Or the people drowning, trying to make it across in flimsy boats from Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba. When people are desperate, they are going to take desperate measures to get here. All the deaths on the border aren’t going to discourage them. I know. I have asked them. I have been to Casa Migrante where there’s large groups sitting out on the curb. I ask them “Where did you come from?” They say “From Mexicali’. I say, “What happened?” They say, “We are being sent back by the U.S. authorities”. I said, “Well, are you aware that crossing the desert is dangerous?” And they had little boys as young as ten years old. They were all men but also little boys. They said, “We know, but there is nothing at home. There is no work. We have to feed our families”. Even the prospect of dying in the desert is not going to deter them. In Motion Magazine: What’s the death toll now from here to the Gulf of Mexico? Roberto Martinez: It’s running around 370 a year for the whole U.S. / Mexico border. An average of 1- to 2-a-day. Every day. We estimate in the last seven years close to 2,000. You have to wonder, where is the outrage? In Motion Magazine: Do you get any sense of outrage from other countries? Roberto Martinez: We get a lot of calls from around the world. People are appalled that it’s been allowed to go this long. Can you imagine if 100, much less 600 U.S. citizens were dying crossing the border into Mexico or Canada. What would the U.S. do? They would solve the problem overnight. For some reason or other these lives are not important to them. They are not a priority. In Motion Magazine: And the knowledge doesn’t seem to get out of this area. Roberto Martinez: A lot of this information is suppressed for some reason. The L.A. Times is the only one that internationally, outside of San Diego, publicizes anything. It doesn’t reach the conscience level of people. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

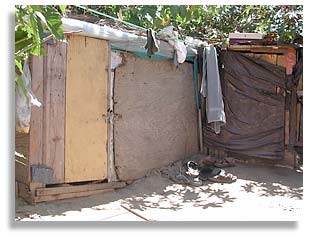

In another case, a group of white kids were shooting from a balcony in San Ysidro, right on the border. A kid was shot in the head and killed - 12 years old - in front of his mother and grandfather. The shooter was only convicted of involuntary manslaughter. He got time-served, one year in the honor camp, and was free. This shows the response by the criminal justice system to hate crimes against migrants. In other words, it’s consistent with the government attitude towards illegal immigration. It’s an insignificant life. A 12 year-old kid. If it been had been a U.S. kid shot in the head by a Mexican immigrant the guy would have been executed. If he lived that long. It’s the attitude that we have in this country toward illegal immigration. I’ve been documenting hate crimes in north county since 1967, when self-proclaimed white supremacists were arrested driving in the back of pickup trucks and shooting down migrants along the road with AK-47’s. One group of four migrant workers was shot down and killed. They were convicted and given life in prison. That’s the kind of thing we’ve seen over and over again. It’s going to be interesting to see what they do with the recent north county case in which eight kids are being tried as adults. In Motion Magazine: Could you go over that case? Roberto Martinez: Last July 8, white kids from Peñasquitos High School attacked five elderly migrant workers in their late 60s. They beat them nearly to death. One of them suffered residual brain damage and other disfigurements. They were all arrested relatively quickly. My organization, CRLA, and some other groups offered a reward, like we did in the Alpine case, ten years ago, when people who committed a hate crime against three farm workers were turned in. In this case, we had a press conference on Friday and by Sunday they had rounded up seven of the eight. The eighth one was on vacation. They arrested him on his return. They were convicted of assault, abuse of elderly, robbery - six different charges. One man, they thought, was going to die. The eight kids came back and dragged his body off and tried to bury it because they thought they had killed him. They had beat him on the head with rocks and iron rods. What made it a hate-crime was that on their shack, their club-house, they had swastikas painted on the outside and ‘white power’. It was one of the worst hate crimes we’ve seen, and I’ve seen a lot against farm workers. We are still waiting to see what the criminal phase of the case is going to result in. What kind of convictions, if any. In Motion Magazine: Can you talk about the migrant outreach project and why you though it was necessary?Roberto Martinez: One of the direct results of this attack on these migrant farm workers by these eight kids was I noticed there weren’t a lot of services, outreach services, for the farm workers in the north county -- the Peñasquitos, Black Mountain Road area. I’ve been going out there for about 20 years and I always knew that the farm workers lived in sub-human conditions, in the canyons, out in the open, no protection. They’ve been victims of not only hate crimes but robberies, assaults by Border Patrol, police, you name it. They are vulnerable to all different kinds of assaults. We are talking about a huge area, tens of thousands of acres of land from Carlsbad on the coast to Palmer Valley and Valley Center. We cover most of it. A lot of the public services that were available have been de-funded. North County Chaplainry, which was a farm worker advocacy group, was de-funded two or three years ago. Friends of the Undocumented, that’s been suspended. California Rural Legal Assistance has been de-funded -- as part of their requirements for receiving federal funds they couldn’t service undocumented workers. That left nothing except community health services which do a great job out there but they can’t be everywhere. So I came up with the idea of trying to start up something again, like I had in ’85 and ’86. I had an office out there but I couldn’t keep it going because I was by myself. I called some people together and we had a tremendous response and we came up with the idea of a migrant outreach project. We thought about getting a mobile unit to reach more agricultural workers.

We moved it to an area at San Luis Rey where people volunteered their time and their money in renovating it and getting it in working condition. Our next project is to raise money for a generator. We are already seeing 30 to 40 workers a day. In Motion Magazine: What do the workers ask about? Roberto Martinez: Mainly they want to know about jobs. That’s the main reason they come here to the United States is to look for jobs. But we are really not a job location center. There’s another trailer that provides jobs, so we send them there. Mainly we want to refer them for medical services, health services, blankets and food, legal services, labor problems. But we also have to train somebody to be able to do that. We have a farm worker who used to work for CRLA who has some experience and we have him running the trailer right now. We’ve had some money donated for that. We are very excited about this project. We hope to be around a long time. In Motion Magazine: What are the primary crops? Roberto Martinez: We have year-round crops. Tomatoes, strawberries, cucumbers, cabbage, avocados and some citrus. In Motion Magazine: How many workers are in that area? Roberto Martinez: In the north county, between 15 and 20,000 workers at any given time. In Motion Magazine: And how many of those are off the books, so to speak. Roberto Martinez: Probably half. A lot of them are legalized through the amnesty. But then a lot of those amnesty people have moved up into more lucrative construction jobs to make more money. In Motion Magazine: What’s the wage? Roberto Martinez: The minimum wage that they are supposed to pay is $6.25/hr but in agriculture they can legally get away with paying them one dollar less an hour. You can imagine that workers who come from the poorer states in Mexico are grateful for $3 to $4 a day or even $5. In Motion Magazine: And that’s the going rate? Roberto Martinez: Yes. And they don’t get benefits or vacation. We are still a long ways from correcting a lot of wrongs in agriculture. In Motion Magazine: Where do people live? Roberto Martinez: All over. It’s a huge area from the coast, inland. In Motion Magazine: Do they mostly have housing? Roberto Martinez: No. There’s only one grower who out of his own pocket built some barracks, very nice ones, for his workers, and that’s Harry Singh, the Singh tomato farms up in the extreme north, near Oceanside. He has very nice modern facilities for his workers. But they have to be documented workers, to protect himself. In Motion Magazine: Where does everybody else live? Roberto Martinez: Everybody else has to find their own place to live. What a lot of workers do is they get together in groups of four to eight and rent a place. They share the costs in the barrios of Carlsbad, Oceanside, San Marcos, and Vista. A lot of the legalized workers, primarily indigenous Oaxacans, Ixtecs who have their green cards, a special agricultural worker green card, live in Tijuana and commute every day to work in north county. Of course, it’s cheaper to live in Tijuana. There’s a special colonia called Colonia Obrero, obrero means worker, Colonia Obrero which is primarily Mixtec Indians. That’s where they live and commute from everyday to north county. Agricultural workers cannot afford to live where they work. These are affluent areas - Carlsbad, Del Mar, Encinitas, even parts of Valley Center. They have to find living space wherever they can. I’ve visited many of them who live in caves. They carve out a cave in the rim of the canyons and they put plastic over it. And that’s how many of them die. They suffocate. They have candles that they use for light and warmth and that candle ignites the plastic and they suffocate. We’ve had that happen many times. Or, because of the assaults by hate groups and bandits, they lock themselves in the shacks that they create out of boxes and it’ll catch fire and they have no way out. They can’t get out fast enough. They die in there. We’ve seen that many times. They suffer tremendously out there. You can imagine. There is no running water, no electricity, nothing. It’s a very tragic story. In other words, they leave four walls and a roof, basically comfortable where they are from in Mexico, to come and live out in the open here. Exposed to the elements, exposed to danger, robberies, beatings, shootings. It’s unimaginable. I just can’t imagine how they survive. To me, those are the heroes. Contribution to the Mexican economy In Motion Magazine: And a lot of the money they make is sent home to Mexico? Roberto Martinez: President Fox’s government estimates that approximately twenty million Mexicans living in the United States send home close to $7 billion a year. That goes directly into the economy. Into the communities. That doesn’t go to the government. He said that is second only to the income that is generated by the oil that they export. In Motion Magazine: So he’s paying attention not just because of the human rights aspects but the economic aspects? Roberto Martinez: Absolutely, he’s protecting his economic interests. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Roberto Martinez: I’ve been with the American Friends 18 years. I’ve been at advocacy for human rights work for close to thirty years. I started out in east county in the late sixties organizing around police abuse of Mexican immigrants, sheriff’s abuse, and hate crimes. That was my first contact with hate groups in east county, back in the late ’60s. In fact, I was the victim … . I bought my home in 1965, in Santee, and the day before I moved in, before I brought my family from Logan Heights, I went to check on the house to see if it was ready. I noticed that the people who had been renovating the house, the construction people, pulling off the wall panels. So I said, “What’s wrong?” He said, “We had vandalism here last night.” But he wouldn’t tell me what happened. So I looked at the paneling on the ground outside and it said, ‘Get out of town wetback’. They had carved swastikas on there. That was my welcome to Santee, in 1965. I didn’t realize I was the first Mexican family to move in there. I stayed because I had already invested a lot of time and money to buy that house. It was a used house. A couple of weeks later, the first black family moved in up the street, a very prominent doctor, and they burned a cross on his lawn at night, broke his windows, spray-painted swastikas on the outside of his wall. He moved out. Next day he was gone. This came out in the paper. I realized what I got myself into, but as more Mexican families moved in I found I had to start organizing them, just for our own protection, for our culture. As the kids got old enough to go to high school, it was worse. White kids would come to school with t-shirts that said white power in front, and on the back it said Youth Klan Korp. And the principal at Santana High School allowed them to recruit. Then, if that wasn’t bad enough, they started waiting for the Mexicans as they got out of school and they would attack them and beat them. Finally, one summer, I think it was 1970, I had already emerged as an organizer in the community, some people came to my house, and they brought their kids with them. Four kids were badly beat up, three boys and a girl. I said, “What happened?” “We got beat up again. They waited for us after school. They were yelling, ‘Go back to Mexico’ and ‘Wetbacks’. They had two by fours. The sheriffs came and they only arrested the Mexican kids. They put us in juvenile hall.” The girl was choked by the sheriffs. Her throat was all purple and she was bleeding from the mouth. We took her to the hospital. And something just overcame me right then. I said, “This is it. I have to do something.” So I called the school and I said, “I want a meeting tomorrow morning, ten o’clock, to talk about this”. They said, “It’s already been resolved. The sheriffs have taken care of it.” I said, “No, they haven’t.” I said, “We’ve got to meet.” And he said, “No, you can’t.” Then, I called the sheriff and I said, “I need a meeting tomorrow at ten o’clock at the school. There’s some police brutality problems here. Your officers overreacted”. He said, “No, it’s all resolved.” So, I sat back and I waited about an hour and decided what I was going to do. I called both of them back and I said, “I want a meeting,” I called the vice-principal and I said, “I want a meeting here tomorrow morning.” I said, “If you don’t meet with us I’m going to hold a press conference here and we are going to call it what it is. It’s racial violence and you are approving it and condoning it, allowing this Youth Klan Korp to recruit.” And he was quiet for a minute and he said, “OK, we’ll meet.” Then I called the sheriff and told him the same thing. “I want you at the meeting at ten o’clock. You, or somebody to represent you, and if you are not there I’m going to have a press conference in front of your station and call it what it is.” And he agreed. That was my first experience of bluffing and organizing the community around this issue. That’s what got me started. Once I did that, the word got out about what I did and I started getting called to other areas, like Spring Valley, Lemon Grove where there was serious sheriffs brutality and little by little up into north county with the sheriffs and the Border Patrol and the police in Oceanside and Escondido. It’s a long story. What was illegal is being made legal In Motion Magazine: How would you assess the human rights situation here over the time you’ve been organizing? Roberto Martinez: The ’80s were the worse. In terms of the Chicano Movement, the ’60s and ’70s were the worse, but in terms of human rights, the border, the ’80s were the worse. At the beginning of the ’90s, things settled down a little bit, but since Operation Gatekeeper started up, the human rights situation has been back close to what it was in the 1980s.

In Motion Magazine: What is behind these ups and downs? Roberto Martinez: The anti-immigrant rhetoric. The politicians use immigration as a platform to make a name for themselves and create hysteria where there shouldn’t be any. They incite people. That they are taking jobs, that they are causing all the crime in the country. The socio-economic problems. In other words, scapegoating them. Scapegoating in California has been going on since the 1930s. In Motion Magazine: Is it a reflection of the economy? Roberto Martinez: Not necessarily. The economy has been strong because of, not in spite of, the economic contributions of immigrants to this country. Their entrepreneurship has created jobs for Americans. We have a $30 billion agribusiness in California. How do they think it got that way? It’s been through the back-breaking work of cheap labor going back a hundred years. Not only by Mexicans but Japanese, Filipinos, and even the poor white people that came from the South, the dust bowl areas. I know. I used to work there, in Bakersfield. I got to see all the different groups. People from Oklahoma, Filipinos, African Americans, but primarily Mexican agricultural workers. In Motion Magazine: How do you feel about your work of the last 30 years? Roberto Martinez: It is rewarding. To me it’s a privilege, not a job. I don’t have to do this because I’m a 6th generation U.S. citizen. I had a very lucrative job as an engineer up until 1977. I was making a lot of money. I bought my home. But I wasn’t happy. I’d always worked from high school, on, in the community, volunteer work. I was always doing something and I knew that was where my heart was. Working with people. Helping people. Working for some kind of justice for our people. But I also wanted to be part of the American dream. I wanted to get an education and make money like everybody else and have nice things. Yet, I still wasn’t happy. So in 1977, I sacrificed my job, in some ways my family, and started over again working in the community. I had to work my way up. But I was happy. I was helping people with problems, organizing, basically trying to correct a lot of wrongs that I saw going on in the community. I wasn’t sure yet how I was going to do it. But I knew that somehow it would come along, the answer would come along - and it did. These last thirty years have been very rewarding. A lot of sacrifice, a lot of hard work, but I see now that I did the right thing. In Motion Magazine: What do you think has been the impact of your work? Roberto Martinez: I haven’t done it by myself. I’ve always worked in coalitions and groups. I think we’ve helped a lot of people get justice in some of their problems but also I’ve seen the larger picture, the impact of exposure. I think what we’ve done, in different ways, through the media and through public demonstrations, is to expose the issue more than it’s ever been. And. I think a lot more people know about the problems more than they ever did. I think that has lead to some changes. If I’ve accomplished that then I think that I can say I did something. I left a mark, so to speak. In Motion Magazine: Has the whole situation become more sophisticated? Roberto Martinez: Technology has taken over a lot of this. We have become more sophisticated through computers and the Internet and Web sites and e-mail, and we have been able to network better that way. In other words, I’m not working here alone. We’re not isolated. We are connected to groups across the border in Mexico. But also, the Border patrol and the INS have become more technology-oriented in terms of the border. I read that they have $30 million worth of technology, and a lot of it is military. The infra-red, the Ident System. Migrants are now processed through electronic fingerprinting and photographs. They get $4 billion a year more than we do a year. Their budget is higher even now than the FBI. In Motion Magazine: Where do you think things are going, your work and the work that will be carried on? Roberto Martinez: I’m sure it’s going to continue the way it is now, but I’d like to see us also get into more research, more studies of issues of the border. In Motion Magazine: Why? Roberto Martinez: I think a better understanding of why people come here, where they come from, may be helpful to us and to the Mexican government. We have done some studies that I think are important. I’d like to see more of those done. We will always continue to do the hands-on, human rights documentation, and filing, and suing that’s got to be done, but I’d like to see us going more into research. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Published in In Motion Magazine - December 4, 2001 Also read these interviews:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2021 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||