|

Brushstrokes for Liberation:

The Art of Oscar López Rivera by mariana mcdonald

Quick Links:

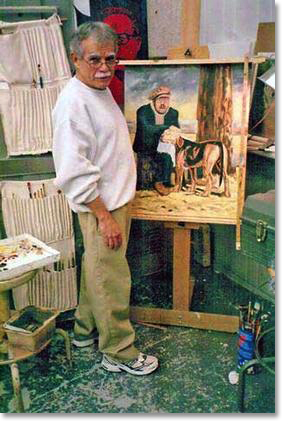

"It’s very difficult to do art in prison, because the limitations are enormous." The understated words of Puerto Rican political prisoner Oscar López Rivera reflect both the realities of the U.S. prison-industrial complex and the challenges of a political prisoner making art a weapon of resistance. To understand how Oscar developed as a renowned artist in such a poisonous environment, we examine his history. Oscar López Rivera is a Puerto Rican political prisoner who has served more than 34 years in U.S. prisons, among the longest-held political prisoners on the planet. Convicted in 1981 of "seditious conspiracy" -- that is, conspiring to use force against the authority of the United States over Puerto Rico -- for his commitment to the independence of Puerto Rico, Oscar was not accused or convicted of causing harm or taking a life. He is nevertheless serving a sentence of 70 years in the U.S. "gulag." He is among the longest held political prisoners in world history, and is considered by many to be the Mandela of the 21st century. Born in San Sebastián, Puerto Rico in 1943, Oscar moved to the U.S. as an adolescent. He was drafted to fight in the Viet Nam war, where he first began to understand what it means to be Puerto Rican in the United States. His brave and unflinching service in Viet Nam earned him the Bronze Star. Upon returning to Chicago from Vietnam as a decorated veteran, he saw how drugs, unemployment, poor education in the Puerto Rican community had reached crisis levels, and began organizing to improve the quality of life for his people. He was a co-founder of both the Puerto Rican High School and the Puerto Rican Cultural Center in Chicago. As his tireless work won the community’s respect, he also won the attention of repressive forces. With other young Puerto Ricans, Oscar decided their work for the independence of Puerto Rico had to be done in clandestinity. Oscar was arrested in 1981, accused of being a member of a clandestine force seeking independence for Puerto Rico, and sentenced to 70 years for seditious conspiracy. From 1986 to 1998, he was held in solitary confinement in the most repressive maximum security prisons in the federal prison system. U.S. Repression of the Puerto Rican movement The treatment of Oscar Lopez Rivera is part of a long history of U.S. repression of the Puerto Rican independence movement, and resistance to U.S. domination and control (see Denis, 2015). Puerto Ricans have resisted colonialism since the days of the Spanish empire and have been imprisoned for their actions. Under U.S. rule beginning in 1898, there have been some 2,000 political prisoners whose sentences added together come to 11,116 years (Susler, 2006). There have also consistently been active popular-based campaigns for the release of those in custody. In the last century successful campaigns include the release of hundreds of Nationalists detained in the 1950 uprising; the 1979 presidential commutations of the Nationalist Lolita Lebrón, Rafael Cancel Miranda, Irving Flores, and Andrés Figueroa Cordero, and the 1999 presidential commutations (Susler, 2006). Oscar López Rivera was among the prisoners given the 1999 offer, which excluded two of his comrades and would have placed conditions on his release. He refused the offer as unacceptable. In 2011, The U.S. Parole Commission denied Oscar parole, ordering he serve another 15 years before being considered again for parole, when he will be 83 years old. A petition asking President Obama to exercise his constitutional powers to grant Oscar immediate release enjoys wide support. In spite of 34 years of adversity in prison, Oscar has maintained his integrity, spirit, and political principles. He keeps fit, reads voraciously, stays up to date with current affairs, and writes. The narrative of his life and years in prison, Between Torture and Resistance, created from letters to family, friends, and comrades, was published in 2013. His beautifully crafted and moving "Hands on the Prison Glass,” essays in the form of letters to his granddaughter Karina, can be read at the National Boricua Center for Human Rights Center (NBHRN) site: www.boricuahumanrights.org . Oscar’s daughter Clarisa lives in Puerto Rico, and her daughter Karina is currently in graduate school in the United States. Because of harsh prison conditions, including non-contact visits, Karina was not able to touch her grandfather until she was 9 years old. He has also become a talented and prolific artist. Oscar’s development as an artist was the subject of a 2013 interview with Puerto Rican newspaper Claridad, in which he talks about how art was not a luxury made available to him as a child (Cotto, 2013).

Oscar’s busy life as a community organizer didn’t leave much time for artistic endeavors. It was only when he was in prison in solitary confinement -- for a total of twelve years -- that Oscar decided to develop artist skills.

Oscar continued to develop his artistic skills and eventually became a teacher of art in the prison. His role as teacher arose eight years ago at the initiative of a prison official who asked him to organize a class. Even though it’s a project of the prison, Oscar revealed how this activity is also limited, as it depends on the number of jailers available to “maintain” the group.

The intensification of repressive conditions in U.S. prisons as a result of the “war on drugs,” including budget cuts and crowding, has exacerbated difficulties.

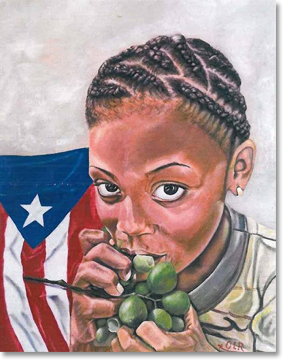

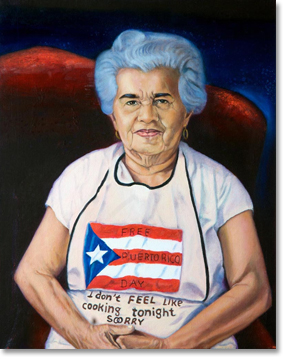

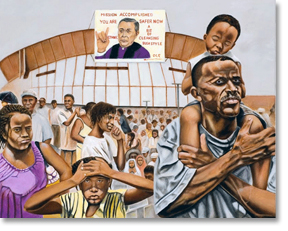

In the Public Eye: Oscar’s Art Reaches World Audiences Oscar’s art quickly gained wide attention and respect, and became one more arm in the struggle to illuminate his country’s plight and to gain his release. His paintings have been exhibited widely. Two key initiatives, in 2006 and 2013, took his work on international tour. “Not Enough Space” International Exhibit The art exhibit "Not Enough Space" was a joint exhibit in 2006 of Oscar’s paintings and the ceramic art of fellow prisoner (released in 2010) Carlos Alberto Torres, sponsored by the Puerto Rican Human Rights Committee. It was designed to draw attention to the two artists’ 25 years of imprisonment. The exhibit was on display in a number of Puerto Rico’s oldest cultural institutions throughout the island (NBHRN, 2015). The National Boricua Human Rights Network (NBHRN) coordinated "Not Enough Space" in the U.S. in Chicago, Cleveland, Los Angeles, New York City, Philadelphia, and San Francisco. It was also displayed in Morelia, Mexico, and Venezuela. Antelsala de la libertad/Prelude to Freedom Exhibit, 2012-2013 The Puerto Rican Committee for Human Rights initiated the exhibit "Antelsala de la libertad/Prelude to Freedom Exhibit" in 2012 at the Claridad Festival in San Juan in February, and the commemoration of the birth of Independence leader and poet Juan Antonio Corretjer in March in Ciales. It also toured a range of cities on the island in 2013. Current Campaign for Oscar’s release Today, the promotion of Oscar’s art is one of many aspects of an increasingly broad, diverse, and united movement for his release that is active in Puerto Rico and the United States as well as numerous countries, including Venezuela, Cuba, and Spain. From April 25-May 29, 2015 the island’s movement in solidarity with Oscar undertook the second Caminata, or walk, for his release, walking 40 coastal towns in 29 days, conducting education and organizing each step of the way. Local officials in 36 of the 40 towns passed proclamations calling for Oscar’s release. On May 30, over 5000 people from Atlanta to Vermont, from diverse backgrounds including church, union, and veterans groups, marched the streets of New York City in "One Voice for Oscar," demanding his release. A June 14 independence march in San Juan was focused on Oscar’s release, as was a June 22 march on the eve of the U.S. Decolonization committee’s consideration of Puerto Rico. Oscar was the absent "grand marshal" of a Gay Pride march on the island in June. Oscar’s release was a key demand of the national Puerto Rican Day parade in New York City June 14, and in Chicago June 20. Oscar López Rivera: Brushstrokes for Liberation Oscar López Rivera’s art inspires, stimulates, and reinforces the growing movement in support of his release and in support of the decolonization Puerto Rico. A fellow Puerto Rican prisoner, released in 1999, and fellow accomplished artist Elizam Escobar speaks eloquently about Oscar’s art as a weapon for struggle and liberation:

Petition to President Obama: Write to Oscar: For more information contact the author at marianamcdonald at yahoo.com, and visit the NBHRN website at www.boricuahumanrights.org

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2015 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |