|

Moments of Grace

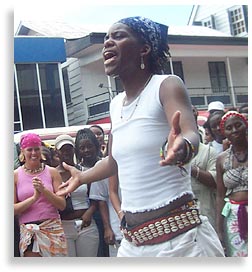

There comes a moment in time during any project endeavor, no matter how successful the project, when the person in charge scratches his or her head and says [if not thinks], why in the world did I do this? I had arrived at that moment this particular day. I had been Suriname for about 14 days, during which I had been teaching community dance workshops daily, sometimes up to three classes back to back. My body was used to the pace, my muscles cooperated and no longer left me sore, but I was tired. The calluses on my feet were starting to take on a life of their own. This particular day I was teaching dance for a collaborative arts project. It was scheduled to last for 5 hours. 5 Hours of exchange of different dance, songs, spoken word, and music forms. It seemed like a great idea at the time. I had agreed to lead it with two other women, a theater director, and a musical director, both experts in their trade and well respected. We had chosen the theme, “Can you see me now”, aiming to use the different art forms to make a statement about who we are as diverse human beings, and how we wanted to be seen. It seemed like a great idea at the time. We were well into the first hour and I had led the dance warm up and was teaching a West African dance class. This 5 hour long session came for me straight after teaching a dance workshop for about 40 students. And so, what had seemed like a great idea at the time, was now turning into a mere quest for the finish line, at least for me. Why in the world did I do this again? I swallowed the question and continued to teach. I turned my back on my students, so they could follow my moves, and as I focused in on the drummer, establishing a connection and hoping for a surge of energy, I went into my automatic pilot mode. I let the drums carry me over my fatigue and executed the steps to my satisfaction. I stopped, took a deep breath, and turned around. I had to see how my students were progressing. I knew that my dance company members would be fine, but I definitely had to pay attention to the other artists. For many of them this was the first time they were exposed to this type of dance. I lifted my eyes, expecting to see a group of attentive students, eagerly awaiting the next step, as I had so many days before. What I saw, instead, startled me. My pupils were not staring at me, on the contrary, they didn’t even notice me. Rather, I saw people scattered throughout the room in groups of twos and threes. They were working together, sharing, learning… “Let me help you; let me show you how to do it; how does that go again?” In Dutch, English, and Surinamese people were communicating with each other. Americans, Creoles, Maroons, momentarily caught up in a common goal, forgetting about the ethnicity that divided them. Where language came short, body language took over. In that moment God yanked me by the ear and reminded me what all this was really about. It was not about me, or my skill development as a teacher. It was not about my fatigue, my weary feet or my ability to communicate. It was about seeing the Creator’s work in action. This is how it was supposed to be. It unfolded in front of my eyes. I had facilitated the space and Spirit was moving and doing the rest, transforming people, bringing them a little bit closer to their higher selves. Somehow I remember there being a lot of light, even though I know it was in the evening. Maybe it was the light bulb that went off in my head as I reconnected with my purpose. I smiled and whispered “Thank you” as I gathered my strength to call my students together to continue the lesson. “Okay people, let’s move on!” Let’s move on indeed. II

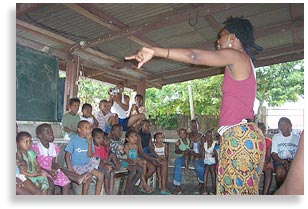

In 2000 we visited and danced with the children in the orphan village. On both occasions people were really appreciative of our efforts. Apparently, they don’t get many visitors. This time around it was very important to me that my students share in this experience of giving. And it was not so they could feel good as “do-gooders”. I wanted them to understand that they are privileged. No matter how much they may struggle as students in the United States, given the mere fact that they are from the United States has placed them in a position of privilege. That is not necessarily a bad thing; it is what it is. But a position of privilege has to be accompanied by a sense of responsibility. So I wasn’t really interested in getting my students to feel good about giving. I was interested in getting them to understand that because of who they are in this world, they must give to those who have less. Through the Elsie Bourke Ewing grant from the University of Kentucky we were able to buy school supplies. I was having some trouble selecting an institution or program that would best benefit from the school supplies we had brought along. Initially I wanted to go back to the orphan village, but I was told that because they are part of an international organization they are actually well provided for compared to other children in the city. I ran into stumbling blocks with another institution. I changed strategies. I looked up and said, “Okay, do your thing. I know you will make sure it gets in the right hands at the right time.” and I let it rest. Two days later my friend told me about a family who without government support takes in and provides for abandoned children. They built a compound out of their own funds, and although they struggle, they manage not to turn anybody away. There was my answer. As we entered the compound, we were treated as honored, yet strange guests. The contrast could not have been starker, about 35 children ranging in age from 1 year to about 16, and us, some rich people from America. They were all black, we were diverse in make up, but had mostly white people in the group. The children looked at us curiously, we felt uneasy. We were seated in front of the children under the canopy on chairs; they sat on benches, more uneasiness. I really had no idea how to proceed; I did not have anything planned. Some transaction had to take place. Sure we brought gifts, but this was not just about school supplies. “Do you your thing and guide me through this”, I summoned my Spirits silently. They never fail to oblige. I called on my brother Darrin, who is well on his way on becoming a Master Healing Drummer. The children’s eyes widened as he unpacked his drum. His hands touched the skin and started beating it. Sounds filled the air, transforming the atmosphere. Without speaking a word, through the use of the drum he was able to entice the children into clapping, moving, and laughing in their seats. It was my turn. With the help of the drum we sang introductions, going around everyone in the circle. Young and old proudly proclaimed their name to the drumbeat. “Sin gin gin gin, gimme tandazo!” I went back and forth in call and response with our young audience in a Zulu South African resistance song. “We are here because our mothers prayed for us” the song translates. It was ironic really, as I thought of the mothers who abandoned these children, if they even were alive. But then I looked at the housemother, and I knew that the song was appropriate indeed. The song ended, the drum continued, it was time to dance. Under much laughter we pulled out some of the boys to dance. They resisted but complied. Then it was time for the girls. I love the “I can’t believe you are making me do this” look. They participated anyway, it never fails. The magic of music, song and dance had worked, it always does. Quiet returned as we started handing out the school supplies: notebooks and markers to the children, and the remaining supplies to the housemother. I don’t know who started it, but one of our members drew a child’s portrait in their notebook. From that instant the dam was broken. Children burst from their seats, the noise level steadily rising as they pursued my dance company members who had been transformed into personal artists. I listened and watched as children spoke Dutch, explaining their artistic desires to their American documenters, as I ate my homemade ice-cream; coconut milk with sugar. For the most part it was clear what a child wanted, but the least bit of variation by one artist, like adding a flower to the picture, would cause a change in demand by the young patrons. I was called over to translate for a little three-year-old girl with the biggest Bambi eyes I had ever seen. “She wants you to draw her a butterfly”. “He wants you to draw him a flower”. I moved from one artist to the next, translating demands. My people who had looked so different, distant, and uncomfortable at first, had to be pulled away from their captive audience. “We really have to go, guys”, I had to repeat several times. Reluctantly they left and were greeted enthusiastically by their new little friends. It has been said that philanthropy serves the philanthropist. There might be some truth in that. We all felt good when we left. Indeed it felt good, but not in a patronizing way. With the right intentions, some drumming, song, dance, and colored markers, barriers were broken and connections were made. Yes, the school supplies were nice and helpful, but the benefits for all those involved will extend far beyond the material exchange. We are all special people, special enough that someone should go out of their way to care for us and make sure we are okay. We deserve to know that we are worthy of being loved, even when our parents abandon us. To be loved and appreciated for who you are is your basic (B)earthright. Some of us are denied that basic knowledge because of our life circumstances. But even those of us who live privileged lives, we become too busy or side tracked, and we too forget. I believe that this exchange provided an opportunity for all involved to connect with that what makes us special. Sometimes we forget how special we are, and sometimes we need to remind each other. My special Spirits tell me so. About the author: Aminata Cairo Baruti (formerly Sandra Cairo Baruti) was born and raised in Amsterdam, Netherlands, but has her roots in Suriname, a small country on the coast of South America. Suriname is known for its multi-ethnic society, and for its retention of traditional African culture. Being raised in Amsterdam contributed to an even deeper understanding of being a member of a multi-cultural society. Upon graduating high school Aminata moved to the United States in 1984, to pursue her college education. She received a bachelor's degree from Berea College in physical education and psychology, and a master's degree in Clinical Psychology from Eastern Kentucky University. While pursuing her academic goals, Aminata became actively involved on the community level, promoting the arts through Kentucky through affiliation with numerous groups ranging from the Nia African Day Camp to the Governor's Scholar's Program. She also danced as a company member with Syncopated Inc. in Lexington, KY. After working at Eastern Kentucky University for a year she left for the Washington D.C.-Baltimore area in 1992 to pursue her dance work more intensively. There she promoted the arts as a program director for a performing arts program, and danced as a company member with the Sankofa Dance Theater, a traditional African drum and dance performance group in Baltimore, Maryland. She further promoted African American dance culture on an individual basis through the Baltimore-Washington D.C. area, teaching numerous dance workshops for young and old alike. While in Baltimore, she joined forces with Kay Lawal (actress/comedian) and Nataska Hasan Hummingbird (singer) and started presenting healing-through-the-arts programs for women. In a visit to Suriname, in 1996, she was instructed by her family in ritual ceremony to take the message of healing through dance to the community. Upon return she received a scholarship to study arts as a tool for addressing community issues with the Urban Bush Women. Aminata Baruti returned to the Kentucky region in 1997, initially as Program Coordinator of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Cultural Center at the University of Kentucky. Since joining the University of Kentucky she has obtained a second master's degree in medical anthropology, serves as an adjunct faculty in the college of social work, and is pursuing her doctoral degree in anthropology on a full time basis. Since her return to Lexington, Kentucky she has been active in presenting African and African American dance forms and culture in the university, public schools, and local communities throughout Kentucky. She has also served as the artist consultant for the Community Involvement Team, which is comprised of local community empowerment centers. She has merged her anthropological work with her dance work and her spirit of community activism. Her latest professional work includes collaborative pieces with the River City Drum Corp from Louisville, choreography for the widely acclaimed theater play Affrilachia by Frank X. Walker, and founding and directing two performance companies. Sabi Diri meaning "knowledge is priceless" in Surinamese, is her multi-ethnic dance company dedicated to displaying and uplifting human and cultural diversity. Spirit Dance Ensemble is her performing ensemble, using life music, song, and dance dedicated to spiritual enlightenment and nourishment. Aminata received a grant from the Kentucky Foundation for Women to study traditional dance in Suriname. Her study tour in 2002 turned into a full blown cultural exchange program as she brought her Sabi Diri dancers and drummers along to Suriname. Upon hearing about the project Aminata received an additional service learning scholarship to support the community service aspect of the project. In Suriname Aminata and the Sabi Diri Company participated in collaborative arts projects, cultural classes, service projects, presented workshops, and performed on several occasions. Guided by her family she continues her mission: using arts to create and recreate spaces where human dignity, respect, and understanding can flourish. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World || OneWorld / US || NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2014 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||